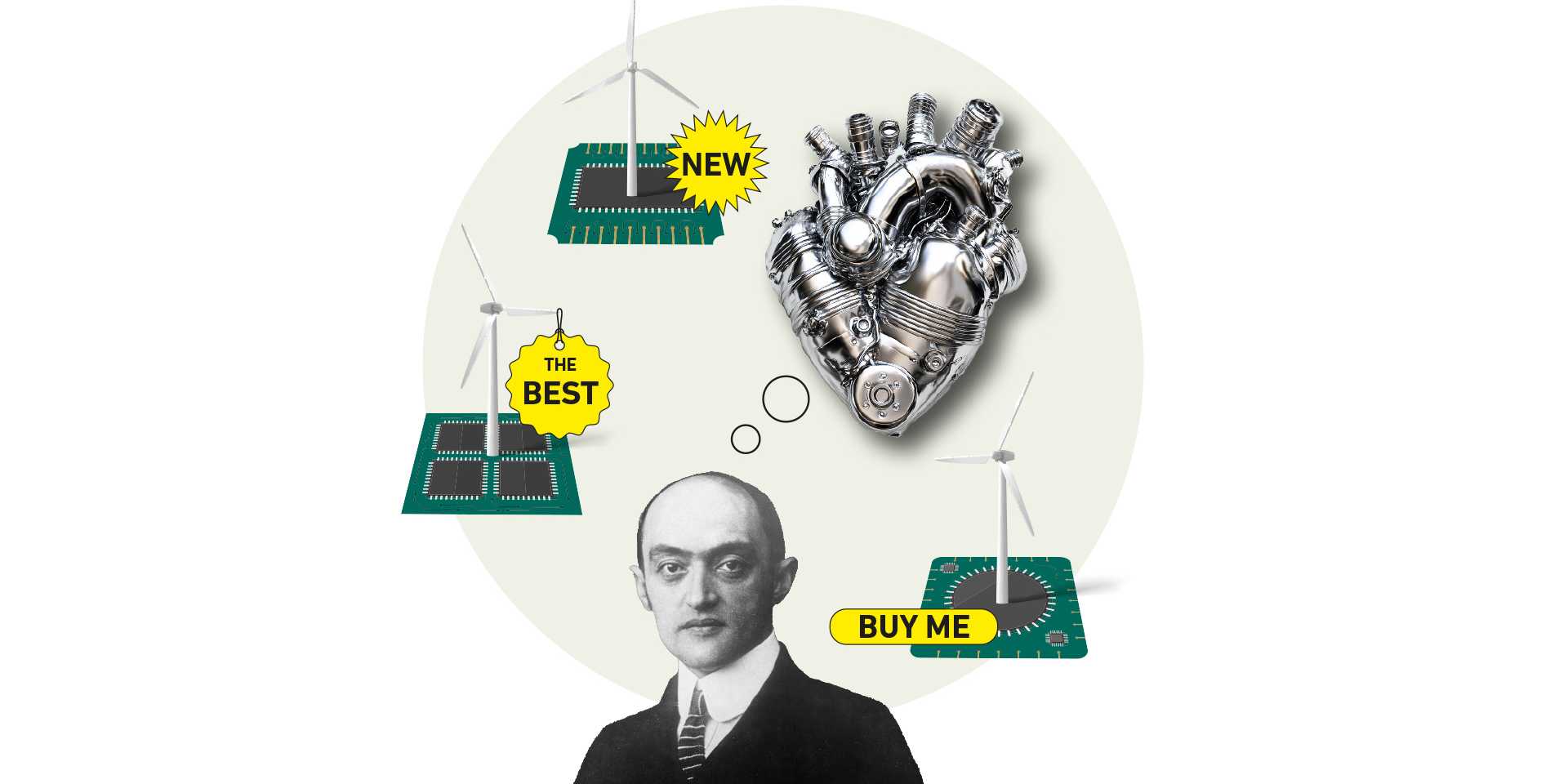

How does innovation come about, Mr Schumpeter?

He developed influential approaches to understanding technological progress and the nature of capitalism. What advice would he give us today? A fictional interview with the late Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter on innovation, digital technology and artificial intelligence.

This fictional interview was created in collaboration with ChatGPT and Perplexity.

Europe is lagging behind the United States and China when it comes to the digital transformation. Why do you think that is?

Well, that has to do with the nature of innovation and creative destruction. Economic progress comes from radical innovation that destroys existing structures and produces new markets. The US and China have created an environment that encourages such innovation. Americans have a strong entrepreneurial mindset coupled with venture capital and a culture that accepts failure as part of the learning process. Companies such as Google, Apple and Microsoft have managed to transform markets through aggressive innovation. China, on the other hand, is pursuing a state-led innovation strategy combined with massive investment in key technologies such as artificial intelligence and semiconductors.

And what is going wrong in Europe?

Europe has excellent engineers and researchers but often lacks dynamism. Bureaucracy, regulation and a lower willingness to take risks stifle much groundbreaking innovation. There is also less capital available for start-ups compared with the US.

What does Europe need in order to catch up?

Less regulation, more venture capital, a stronger link between science and business – and a culture that makes it easier for entrepreneurs to take risks.

Should Europe also pursue more industrial policy and protect its own industries through tariffs, as Donald Trump is currently doing in the US?

Industrial policy can help, but it also poses risks. If the government specifically encourages key industries, this can stimulate innovation – for example by investing in technologies of the future such as AI, semiconductors and renewable energy. If the state intervenes too much, however, there is a risk of bureaucracy, market distortions and inefficient structures. Tariffs can protect certain industries in the short term, but they often stifle competitive pressures – and competition is the engine of innovation. When companies are shielded from foreign competition, they have less incentive to become more efficient or develop new technologies. This can make them sluggish and hostile to innovation in the long term.

Are there also downsides to innovation?

Of course! Every innovation process produces winners and losers. Traditional business models become obsolete and some jobs disappear. This can create social tensions. Examples of this are Detroit, where cars used to be produced en masse and today factory buildings stand empty, or the Ruhr region following the decline of the local coalmining industry in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Cities such as Gelsenkirchen are still feeling the effects of this structural change today. However, this process is essential for economic progress. The challenge is to organise change in such a way that the benefits of innovation are distributed as widely as possible.

What tradition should not be disrupted under any circumstances?

The Viennese coffee house tradition, of course. At a time when everything has to be disruptive, they represent a gentle form of resistance – against ever greater speed, against efficiency mania and against Wi-Fi!

Schumpeter’s theory at its core

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) viewed economic development as a constant process of renewal. His central idea is creative destruction: new technologies and innovations displace existing structures, resulting in progress and growth. Schumpeter saw entrepreneurs and technological innovation as the key drivers of economic activity. However, he warned that bureaucracy, excessive regulation and risk aversion in society could slow down the innovation process. Viewed within the context of the history of ideas, Schumpeter is associated with the Austrian School of Economics and evolutionary economics.

Contact

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland