KOF Globalisation Index: Weaker World Trade Slowing Globalisation

The extent of worldwide globalisation has recently increased only modestly. Protectionist tendencies in many parts of the world are likely to have a dampening effect. Social globalisation is hardly advancing at all. Switzerland, the Netherlands and Belgium are the most strongly globalised countries in the world overall.

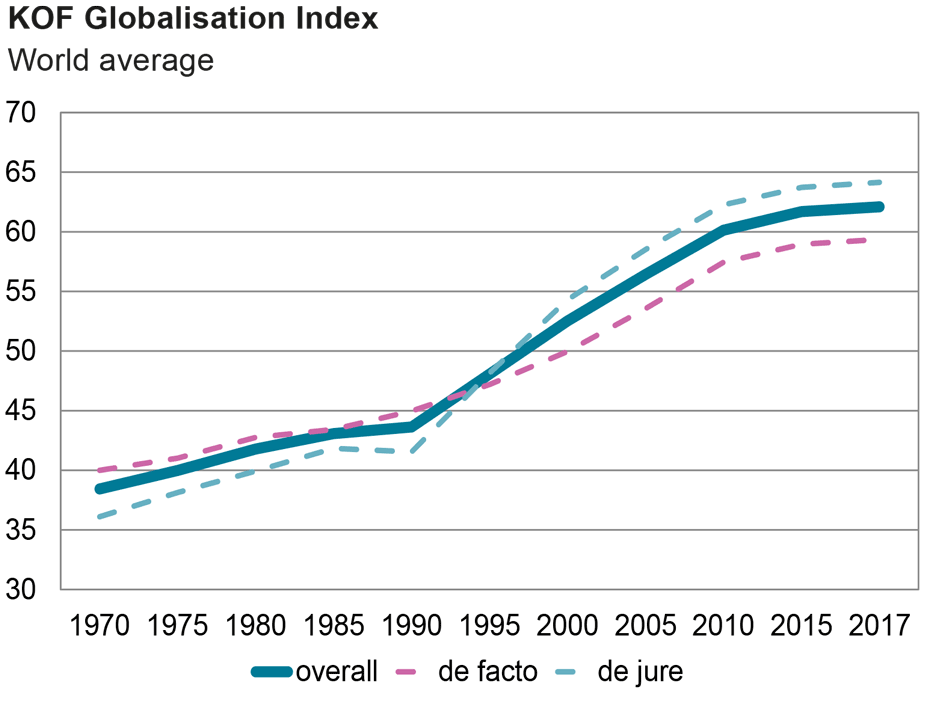

The degree of worldwide globalisation grew rapidly between 1990 and 2007. However, the financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession have curbed this trend. In 2017, the most recent year covered by the KOF Globalisation Index, the extent of worldwide globalisation once again increased only slightly.

Economic globalisation has hardly advanced at all since the financial crisis of 2007. However, a distinction must be made between financial globalisation and trade integration. Whereas international financial flows (de facto financial globalisation) have been growing for the past few years while underlying conditions (de jure financial globalisation) have remained unchanged, trade has become noticeably more sluggish. International trade integration (de facto trade globalisation) has declined since 2014, and the latest trends suggest that world trade is set to weaken further. Although underlying trading conditions have improved since 2014, the ongoing trade conflicts between the United States and China as well as those between the US and the European Union are not captured in the latest index. The US raised its tariffs for the first time at the beginning of 2018, imposing higher import duties on washing machines and solar panels from China, and it hiked tariffs on steel products from various countries in mid-2018.

Social globalisation has hardly advanced at all in recent years either. Whereas the intensity of personal contact (measured in terms of variables such as tourism flows and migration) is stagnating, information flows (measured in terms of variables such as patent applications and trade in high-tech goods) continue to grow. At the same time there are signs of a slight downturn in cultural globalisation. Meanwhile, the degree of political globalisation – as measured by the latest index – continues to increase.

Country-by-country analysis

Switzerland remained the most highly globalised country in the world in 2017, followed by the Netherlands and Belgium. Switzerland is strongly globalised across all categories (economic, social and political). The country has a high trade-to-GDP ratio and is strongly interconnected with other countries in the financial sector owing to its role as a banking centre and the headquarters of many international holding companies. Moreover, the country is also highly integrated from a social perspective owing to its geographical location, cultural diversity and high income levels. And, last but not least, the many international organisations headquartered in Switzerland are likely to have a positive impact on the country’s political globalisation. The countries ranked right behind the top three are Sweden, the United Kingdom, Austria, Germany, Denmark, Finland and France.

Small countries tend to be more strongly globalised than large ones because they are more highly interconnected with neighbouring countries, for example. Large countries conduct a sizeable proportion of their dealings domestically. The world’s largest economies therefore come halfway down the globalisation rankings. The United States ranks 59th in terms of economic globalisation, 27th in terms of social globalisation and 14th in terms of political globalisation. China comes in the lower third of the overall index, ranking 80th. Whereas China ranks 26th in terms of political globalisation, its degree of economic and social globalisation is much lower. Japan – the world’s third-largest economy – ranks 37th. Major EU economies – such as Germany, the UK, France and Spain – are much more strongly globalised overall because of their high levels of economic, social and political interconnectedness within the EU.

Graphs and Tables can be found Download here (PDF, 225 KB).

Methodology

The KOF Globalisation Index measures the economic, social and political dimensions of globalisation. It is used to monitor changes in the levels of globalisation of different countries over a long period. The latest KOF Globalisation Index is available for 195 countries and covers the period from 1970 to 2017. The index distinguishes between de facto and de jure globalisation in the overall index as well as in the economic, social and political dimensions. The index measures globalisation on a scale from 1 to 100. The figures for the constituent variables are expressed as percentiles. The index comprises 42 different variables, which are aggregated using statistically determined weights (principal component analysis).

The economic globalisation dimension includes both trade flows and financial flows. De facto trade globalisation is determined based on trade in goods and services. De jure trade globalisation contains customs tariffs, taxes and trade restrictions. De facto financial globalisation comprises foreign investment across various categories. De jure financial globalisation consists of investment restrictions, openness of the capital account and international investment agreements.

The social globalisation dimension includes personal contact, information flows and cultural globalisation. For each of these in turn a distinction is made between de facto and de jure globalisation. De facto personal contact is measured in terms of international telephone connections, tourism flows and migration, while de jure personal contact is quantified on the basis on telephone line rentals, international airports and visa restrictions. De facto information flows are determined based on international patent applications, international students and trade in high-tech goods. De jure information flows consist of access to television and the internet, press freedom and international internet connections. De facto cultural globalisation comprises trade in cultural goods, international trademark registrations and the number of McDonald’s restaurants and IKEA stores. De jure cultural globalisation is measured in terms of civil rights, gender equality and educational standards.

De facto political globalisation is measured in terms of the numbers of embassies and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as well as participation in UN peacekeeping missions. De jure political globalisation comprises variables relating to membership of international organisations and international treaties.

Contact

No database information available