The Employer’s Dilemma: Is it Worth Engaging Employers in VET Reforms?

- Research Project

- KOF Bulletin

- Vocational Education and Training

As skills mismatch and youth unemployment are high, vocational education and training (VET) systems in many countries are undergoing reforms in order to meet skills demand. Employer engagement is a known component of strong VET programs, but what should employer engagement look like during reform processes?

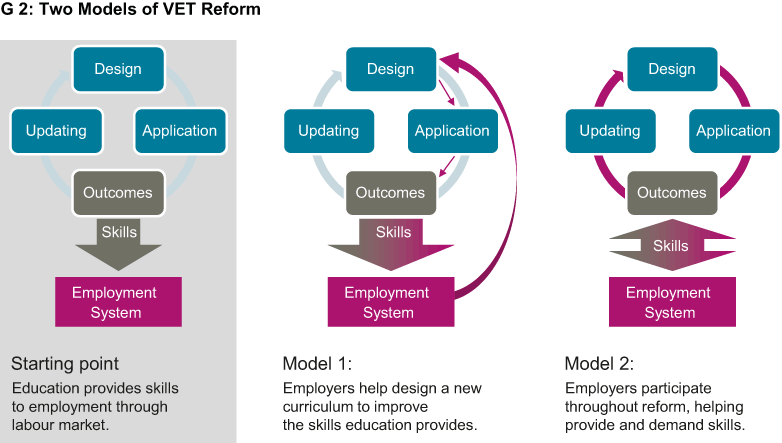

Most reforms start from systems where skills are produced in the education system and consumed by employers, and VET reforms aimed at improving labour market outcomes take one of two forms (see G 2). In Model 1, employers contribute to curriculum development. In Model 2, employers participate in all VET processes: designing curricula, training apprentices, and initiating curriculum updates. In Model 2 employers go from being consumers of skills to being both producers and consumers.

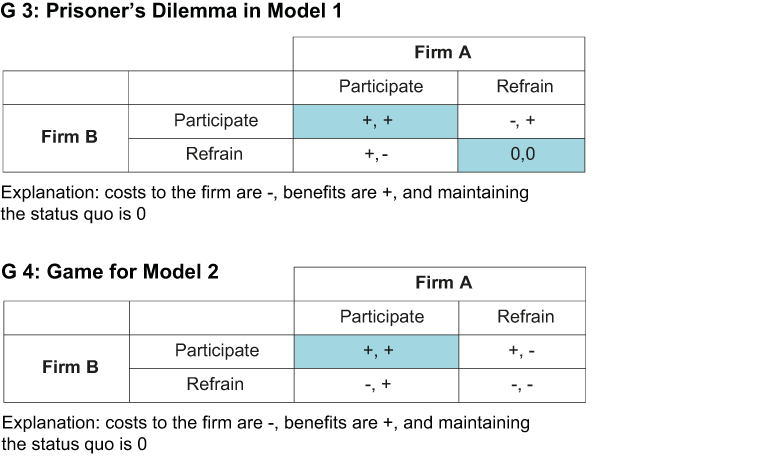

In a new study that analyses employer engagement, Katherine Caves and Ursula Renold argue that Model 1 creates a prisoner’s dilemma that prevents engagement, even though it seems to be the option that requires the least commitment. If firms invest their time and expertise in VET curricula and their competitors choose not to, the competitors may benefit from better skilled graduates without having had to invest. As a result, the investing firms either drop out of the program or reduce their investments. Program quality suffers and the reform fails (see G 3).

Model 2 does not create the dilemma. Apprentices are productive and some stay on after training. This means that the training costs are returned or even exceeded. Firms in Model 2 always benefit from participation regardless of the actions their competing firms take (see G 4).

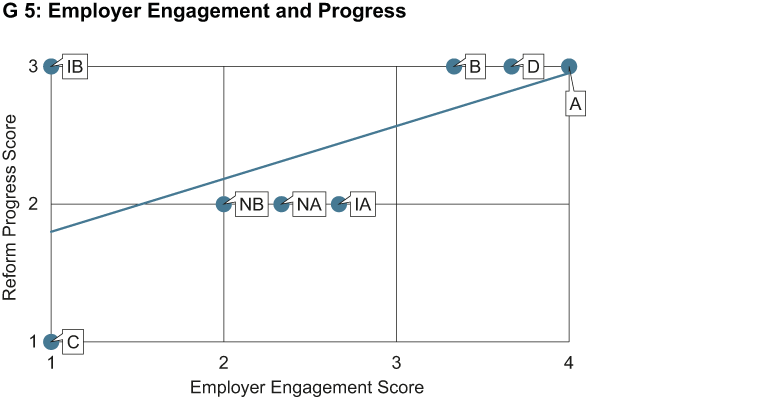

Caves and Renold use case studies of eight ongoing reforms that started in July 2015 to examine engagement and implementation progress. Cases A, B, C, and D are major American cities or states. IA and IB are international reforms, and NA and NB are non-standard reforms carried out with non-government leadership. All cases were part of the 2015 CEMETS summer institute, during which the participants studied VET, revised their reform plans, and participated in data collection. Caves and Renold scored these cases with a qualitative rubric (see KOF Working Paper) regarding their employer engagement. After following each reform case for two years, they rated the progress of each as either stalled (1), progressing incrementally (2), or progressing radically (3).

More engagement, more implementation progress

A comparison of the eight reforms’ progress shows that more employer-engaged reforms make more progress (see G 5). C excludes employers and is stalled. NB, NA, and IA somewhat engage employers and progress slightly. B, D, and A all involve high employer engagement and are progressing radically. IB is an exceptional case with low engagement and radical progress nevertheless. It is worth mentioning that this project was implemented by a strong top-down government.

The authors are able to show that projects which involve employers in the reform process make more progress toward implementing VET. However, employer engagement is not always a necessary condition: top-down reforms can make progress regardless of engagement, though they raise concerns about eventual quality and outcomes.

This study is qualitative; theory-building instead of causal. It is limited because employer engagement is not the only influencing factor. It does not investigate the quality of reforms in terms of outcomes as all of the reforms are still pilot projects. The underlying sample is deep but very small, and the variables are measured qualitatively by necessity. The authors will continue to follow all cases and will add new ones annually.

Employers can change from being consumers of skills to co-producers and consumers of skills. While asking employers to take on more responsibility seems like a counterintuitive strategy for reform feasibility, it actually resolves the prisoner’s dilemma of lower-engagement reforms. As soon as employers are able to recover their investments through the productive contributions and future employment of trainees, they can afford to participate irrespective of the actions of other employers. Involving employers in the implementation of a new or better VET system might seem dangerous to education-based reformers, but it appears to be the safest bet for the progress of their reforms.

KOF Working Paper No. 423 “The Employer’s Dilemma. Employer engagement and progress in vocational education and training reforms” by Katherine Caves and Ursula Renold.

Contacts

No database information available

No database information available