Structural and Economic Changes on the European Labour Markets

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

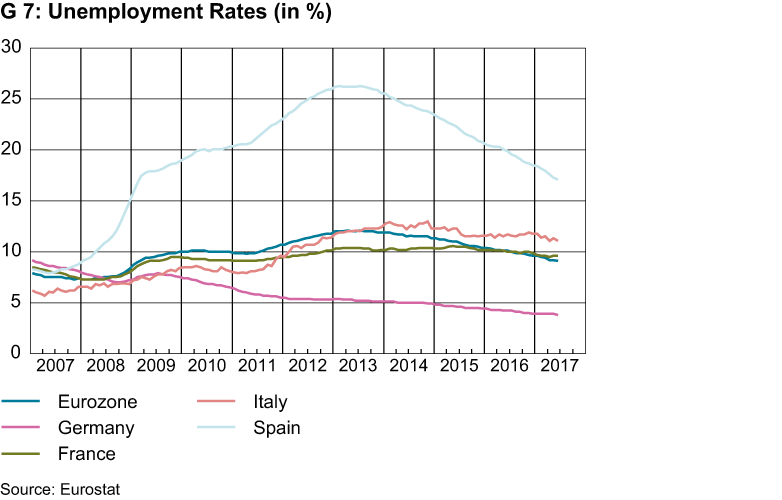

The financial crisis years have made it clear that the labour markets in many eurozone countries were too rigid to adjust to unexpected macroeconomic changes. As a consequence, the eurozone temporarily lost more than five million jobs and unemployment persistently remained above 10 per cent for a long time. Various structural adjustments combined with the economic recovery have led to an improvement of the labour market situation since 2013.

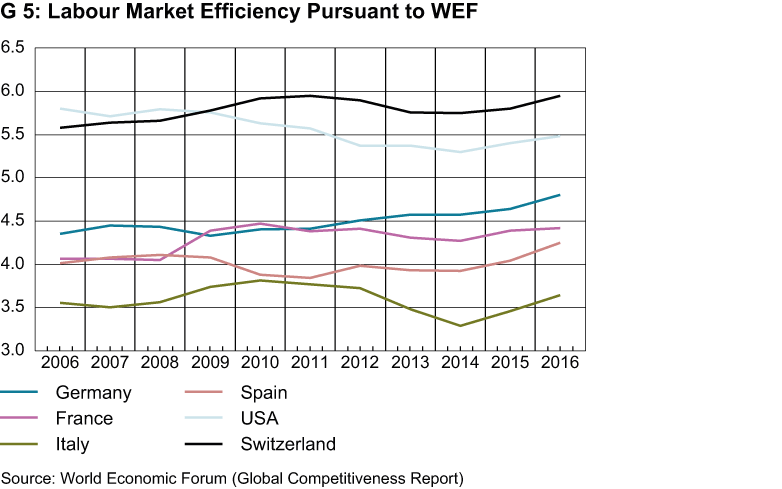

Regulation is necessary to define workers’ rights, provide private households with a secure planning basis and prevent discrimination of certain population groups. However, too much regulation leads to unnecessary red tape, which may slow down job creation, restrict companies’ room for manoeuvre in times of crisis and limit labour mobility in the more productive sectors. According to various indicators, labour market efficiency in the majority of the European countries is low in international comparison. The current ‘WEF Global Competitiveness Report’ suggests that Italy and Spain are particularly far behind other advanced economies in terms of labour market flexibility (see G 5). The ‘Strictness of Employment Protection’ indicator published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also shows that employment protection is much stronger in the eurozone than, for instance, in Anglo-Saxon countries.

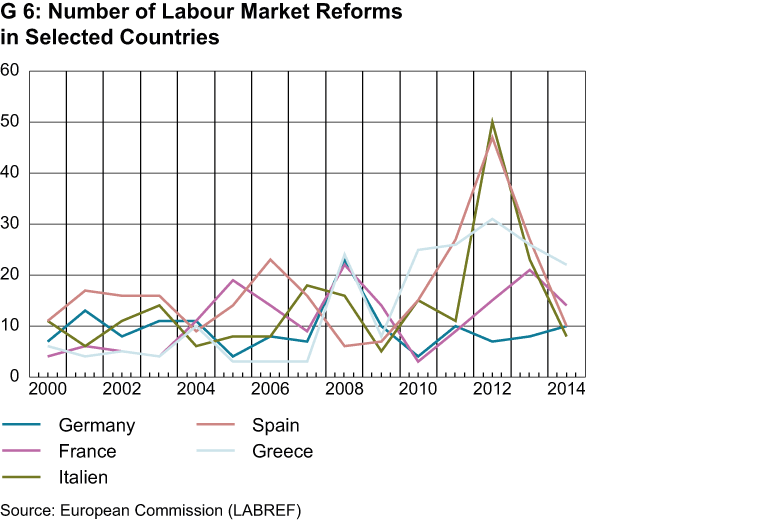

With the aim of reducing unemployment and raising labour market participation, countries have gone to great lengths to make the labour markets more flexible and dynamic in the past few years. Due to cyclical reasons, the majority of post-2007 legislation was part of active labour market policy, for instance government support programmes. During the subsequent economic recovery, employment incentives were introduced on a wider level as well as measures designed to raise labour demand. Numerous laws addressed structural aspects, such as protection against dismissal, wage setting, unemployment support or labour taxation. The majority of the structural reforms were carried out in the former crisis nations (see G 6) 1. Italy and Spain, for instance, have implemented a series of measures relaxing dismissal protection laws to create greater incentives for open-ended employment contracts.

What caused the improved labour market situation?

Since mid-2013, numerous indicators have registered an improvement of the labour market situation. The share of unemployed in the economically active population has steadily declined to currently nine per cent (see G 7). At the same time, youth and long-term unemployment have also dropped consistently. Nevertheless, eurozone unemployment trends still vary considerably from country to country. While the unemployment rate in Germany has dropped steadily to under four per cent since the beginning of the crisis, Spain recorded over 25 per cent in 2013 – a figure that has since declined to 17 per cent in the course of the country’s robust upswing. In contrast, France and Italy have had persistent rates of 10 per cent and 11 per cent respectively.

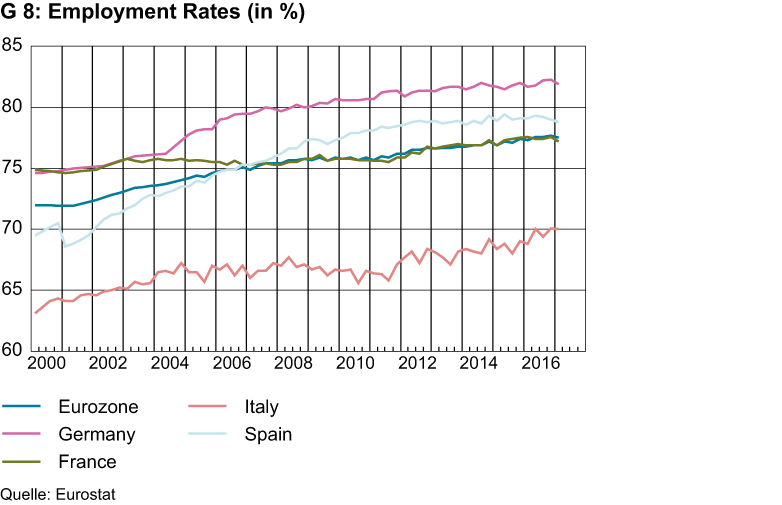

For many years now, the proportion of the economically active population (consisting of employed and unemployed persons) has been rising in relation to the total population in the working age group from 15 to 64 (see G 8). The financial and debt crisis only put a slight break on this trend. In Italy, new legislation has encouraged labour market participation and has even resulted in a significant rise in the employment rate. The main reason why a proportion of the employable population in the eurozone is not working is their participation in basic and advanced training courses. Furthermore, family reasons and especially sickness-related reasons are now playing a bigger role in explaining non-participation in the labour market. Early retirement, in contrast, has become much less frequent and the percentage of people who are too discouraged to participate in the labour market has also declined.

The natural unemployment rate as estimated by the European Commission may provide an answer to the question whether the improvement on the labour market is due to the economic upswing or the structural reforms. The natural unemployment rate indicates the level of the unemployment rate at which wage inflation neither accelerates nor slows down. While this rate has dropped substantially in Germany, Portugal and Ireland, it has hardly improved in Spain, France and the eurozone as a whole. Italy has even seen a deterioration. The economic trend is therefore likely to be the main reason for the development of the past few years.

How does employment reflect the upswing?

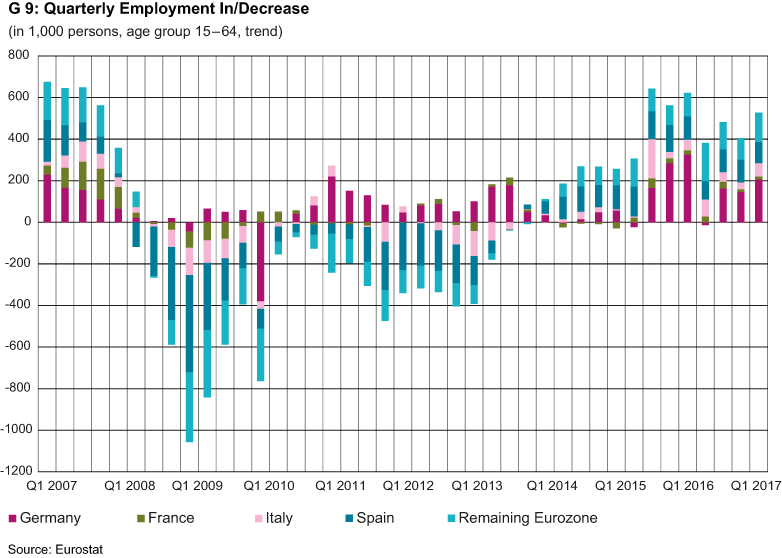

Due to the recession triggered by the financial crisis in the years 2008 and 2009, employment dropped in most European countries, with the peripheral states suffering most. Thanks to the economic recovery and structural reforms, employment in the eurozone has gone up considerably since 2013, reaching pre-crisis levels this year (see G 9). However, in terms of geography, demographics and sectors, the trend has been highly heterogeneous. Aside from the catching-up process in Spain, it was mostly dominated by substantial employment growth in Germany. Since the crisis primarily led to job losses in the manufacturing industry and construction, the worst affected were young, male and less qualified employees. The increase in employment in these categories has been rather slow so far. A widespread increase in jobs across sectors, demographics and countries is only just starting to emerge at the margin.

Structural deficits persist

Necessary reforms to ensure more robust and flexible labour markets have been introduced in many places. In the past few years, they have had a positive effect on labour market flexibility as estimated by the World Economic Forum. However, the dynamic economic development should not hide the fact that there is still room for improvement in many eurozone countries. France, for instance, needs investment in the vocational training system, measures to increase labour mobility and better labour market access for lower-qualified workers. In Italy, persistent problems consist of substantial regional differences in labour market conditions, high youth unemployment and low labour market participation among women. Spain is not only grappling with high youth unemployment but also high long-term unemployment. Over half of all unemployed have been out of work for more than a year, running an increased risk of permanent exclusion from the labour market.

1 The number of laws passed is merely an indicator of the progress of reforms. Germany‘s game-changing Hartz Reforms in the period from 2003 to 2005, for instance, are indiscernible in the graph.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland