Wage Trend in Switzerland: Wages Stagnate, Glass Ceiling Remains in Place

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

In the last few years, real wages have risen substantially in Switzerland – despite the historically weak trend in nominal wages. In the coming two years, however, there may be no real growth in wages. A significant and problematic wage differential continues to exist between men and women.

Historically low growth in nominal wages in 2016

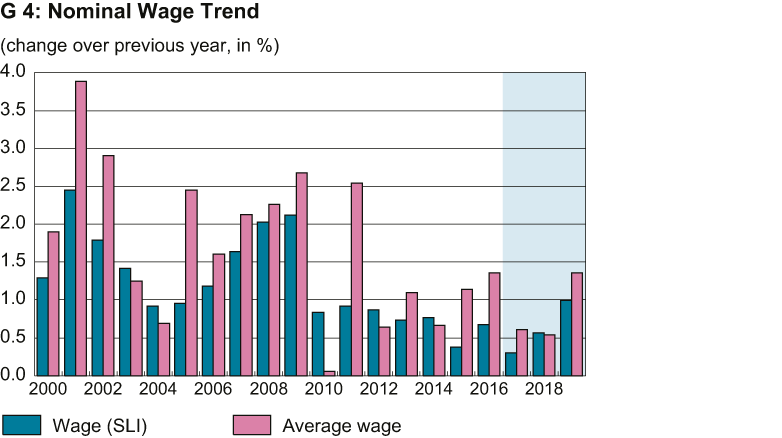

In the last few years, real wages in Switzerland have gone up considerably. Last year, the rise in real wages amounted to 1.1 per cent. This was, however, not due to high nominal wages. According to the Swiss Wage Index (Schweizer Lohnindex, SLI), growth in nominal wages has recently dropped to a historically low level. The Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) reports a nominal wage growth rate of 0.7 per cent for the past year. The latest FSO figures for this year indicate an even lower growth rate (+0.3%). In the entire close to eighty-year history of the SLI, there has been only one year in which the nominal wage growth rate was as low as 0.3 per cent. This was in 1999 when Switzerland started its slow recovery from a prolonged stagnation phase.

Instead, the significant growth in real wages in Switzerland was due to the decline in consumer prices, which led to a substantial increase in the wages’ purchasing power. According to the FSO, growth in real wages was particularly pronounced in the wholesale sector (+2.2%), the finance and insurance sector (+2.1%) and the chemical and pharmaceutical industries (+1.9%). Growth in real wages was considerably lower in food and tobacco production (0.3%) and was even negative in the wood product, paper and print product industries (-0.3%).

Although women’s wages are catching up slightly …

On top of this, a trend which has emerged again and again over the last few years has continued: Women’s wages grew faster than those of men. Last year, according to the SLI, women’s real wages grew by 0.8 per cent, while men’s real wages went up just 0.6 per cent. Over the last 20 years, the average annual growth rate in wages is 1.3 per cent for women and 1.1 per cent for men. A similar picture emerges from the figures compiled by the Swiss Earnings Structure Survey, Switzerland’s most comprehensive wage statistics. The survey covers around 40 per cent of all jobholders in Switzerland. While the wage differential between men and women still amounted to 16.6 per cent in the 2008 Swiss Earnings Structure Survey, it had declined to around 12.5 per cent by 2014.

… wage inequality remains

Nevertheless, in international comparison, Switzerland’s wage differential of 12.5 per cent is very high. In figures: In 2014, the median wage of a full-time male employee was 6,751 Swiss francs, meaning that half of all men earned more than 6,751 Swiss francs, the other half less. For women, the median wage was 5,907 Swiss francs – a difference of 844 Swiss francs per month, or around 10,000 Swiss francs a year. Furthermore, at 15 per cent, the differential was higher in the private sector than in the public sector. This state of affairs results in a number of factors aside from substantial differences in purchasing power. The pay differential may also contribute towards the fact that women’s participation in the labour market is lower than that of men, especially when the households involve care work and housework. Even if the wage difference is small, it appears sensible that the parent who earns more money takes over the role of wage earner while the other parent focuses on care and housework.

Around 60 per cent of the wage differential can be ‘explained’

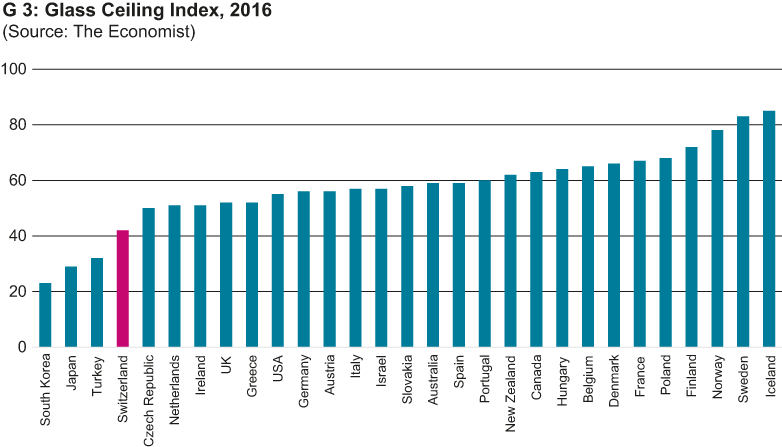

Part of the gender-specific 12.5 per cent wage differential is due to women working in different professions than men, having less work experience on average and coming from a different educational background. The position at work – executive level or below – also contributes towards the explanation of the wage differences. According to FSO calculations, if all of the factors that are included in the Earnings Structure Survey and have an objective impact on wage levels are considered, around 60 per cent of the wage differential between men and women can be ‘explained’. This leaves just five percentage points of the original 12.5 per cent wage differential ‘unexplained’. Breaking down the differential into an ‘explained’ and an ‘unexplained’ part throws an interesting light on the matter. Ideally, it may help to clarify whether men and women in the same job actually earn the same wage (see G 3).

However, this breakdown also masks an essential component of wage discrimination against women on the Swiss labour market, namely the fact that women and men do not work in the same jobs. For instance, one part of the wage differential between the genders can be explained by the fact that women do not earn managers’ salaries. However, rather than an explanation, this is part of the problem: Women are not moving up into management positions even if they have the same qualifications as their male colleagues. This is the so-called glass ceiling effect. According to the Economist’s Glass Ceiling Index, Switzerland ranks particularly high in this field. Among the 29 countries included, only three (South Korea, Japan and Turkey) have a higher index than Switzerland. Among other factors, Switzerland’s unfavourable position is due to high childcare costs and women’s comparatively low representation on boards of directors.

Stagnation of real wages

In the last few years, growth in real wages often exceeded macroeconomic growth in labour productivity. This was accompanied by a noticeable rise of the wage quota in Swiss GDP in international comparison. However, the flip side of this trend, which may be considered positive from a distributive point of view (wage distribution is less unequal than wealth distribution), consists of declining margins for companies. The drop in corporate profitability was not least due to the loss in price competitiveness caused by the Swiss franc appreciation. Low margins limit the leeway for wage rises. Many companies are therefore likely to try and keep nominal wage growth down this autumn. We do not expect nominal wages according to the SLI to go up by more than 0.3 per cent this year. Thanks to the improved economic outlook, at 0.6 per cent, nominal growth will be slightly higher in 2018. However, the growth in nominal wages is likely to be eaten up by a slight increase in prices (see G 4). Real wages will effectively stagnate both in 2017 and 2018.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland