Unemployment Goes Down When GDP Grows by 2%

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

In Switzerland, unemployment begins to decline when GDP growth reaches around 2%. However, the correlation between unemployment and GDP is less pronounced in Switzerland than in other countries. Among the main reasons is the fact that Swiss companies frequently hire foreign employees to meet their staff requirements.

When GDP growth goes up, unemployment goes down. This correlation is also referred to as Okun’s law, after the US economist Arthur M. Okun, who conducted the first in-depth research into the negative correlation between GDP growth and changes in the unemployment rate in 1962. The underlying mechanism is simple: When the economy is booming and demand for products and services is high, companies have a higher need for staff. Since they also hire unemployed individuals, the unemployment rate declines. The opposite happens during a recession.

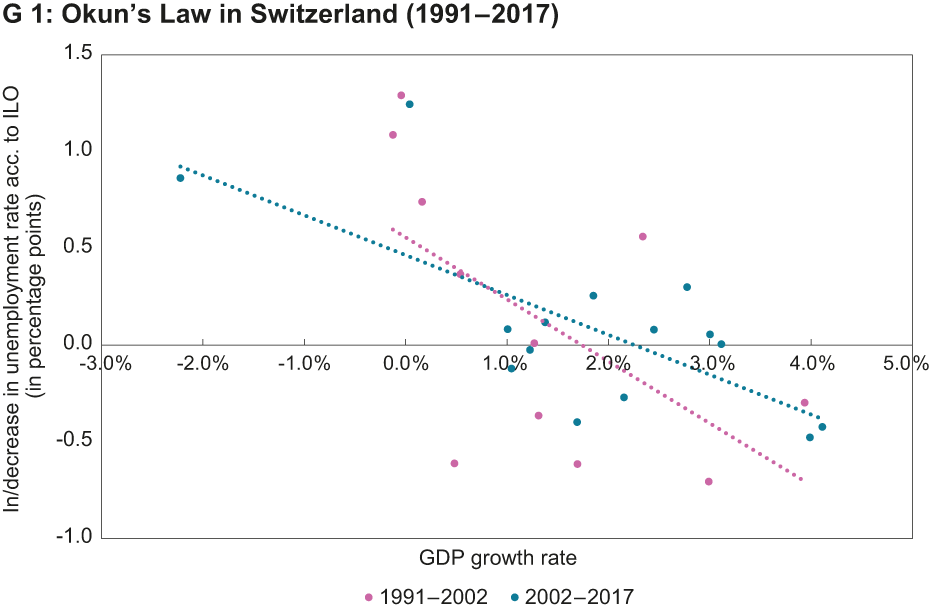

Graph 1 illustrates Okun’s law on the basis of annual data for Switzerland in the period 1991–2017. The x-axis shows the GDP growth rate compared to the previous year. The y-axis shows the year-on-year change in the unemployment rate according to the definition of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). We distinguish between the periods 1991–2002 and 2002–2017. The negative correlation between GDP growth and the change in the unemployment rate is obvious in both periods. The trend lines in the graph suggest that GDP growth of 4% reduces the unemployment rate by around 0.5 percentage points in the same year. However, if GDP contracts by –2%, as it did in the recession of 2009, the unemployment rate rises by close to 1 percentage point.

The ‘employment threshold’ lies at 2% GDP growth

The value at which the trend line meets the x-axis is another central indicator. This point, which is also referred to as ‘employment threshold’, shows which level of GDP is normally required to result in a decline in the unemployment rate in Switzerland. According to our graph, the employment threshold lies at a GDP growth figure of around 2%. However, this also shows that unemployment in Switzerland rises even if the economy records moderate growth, for instance of 1%. There are two explanations for this. Firstly, the labour force grows every year. In order to absorb the additional manpower and prevent an increase in unemployment, employment and hence the GDP must also grow. Secondly, labour productivity is rising steadily. If the value added per worker increases e.g. by 1% a year, production must expand by 1% in order to maintain employment figures.

Comparison of the two periods depicted in Graph 1 impart the impression that the employment threshold has been slightly higher in the last 15 years than in the preceding period. The correlation between GDP growth and changes in unemployment also seems to have declined: The angle of the trend line has become less steep. Hence a given GDP increase or decrease has a smaller impact on the unemployment rate than before. Although one should not overstate the importance of this comparison of the two periods since it is based on a very low number of data points, the conclusion is still relevant: In international comparison, Switzerland was already showing a low correlation between GDP growth and unemployment in the 1990s. In a study conducted by the International Monetary Fund (Ball et al., 2013), among 20 developed economies, Switzerland has the third-lowest correlation between GDP growth and changes in the unemployment rate. According to Graph 1, this low correlation has, if anything, become even lower.

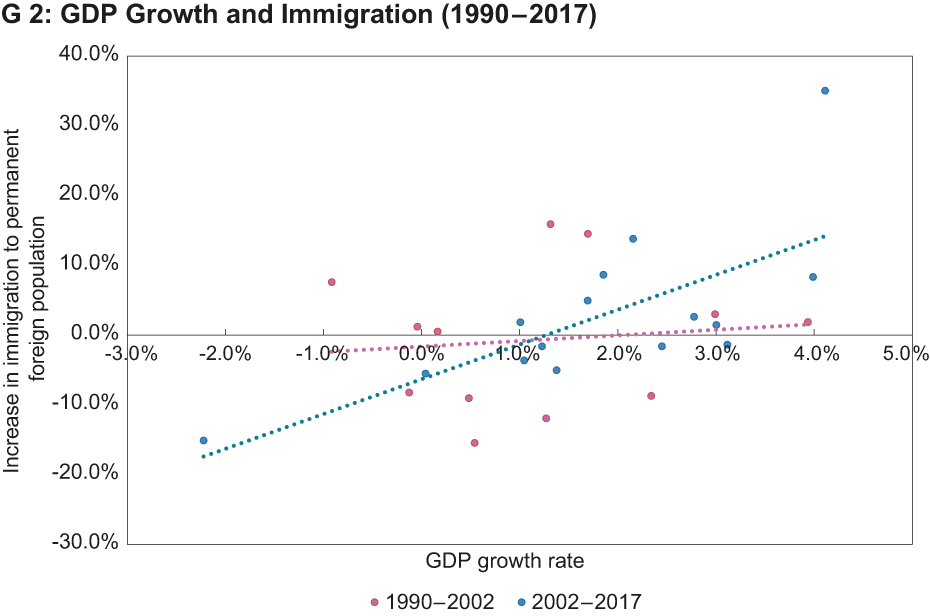

So what is the reason for the fact that the correlation between GDP and unemployment is lower in Switzerland than in other countries? The IMF authors provide a plausible explanation: When expanding their workforce, Swiss companies also hire foreign workers aside from the unemployed. Vice versa, it is traditionally the foreign workers who are particularly prone to losing their job in a recession. If they emigrate again, the decline in employment does not appear in the Swiss unemployment statistics. GDP and unemployment are thus not very closely correlated in Switzerland since the unemployed represent only one of two pools of potential workers when the economy is doing well. By contrast, GDP and employment do indeed correlate in Switzerland – and rather strongly in international comparison.

Graph 2 shows the significant correlation between the real GDP growth rate and the growth rate of immigration into Switzerland, or to be exact, the year-on-year growth rate of gross immigration to the permanent foreign population in Switzerland. According to Graph 2, GDP growth goes hand in hand with an increase in immigration into Switzerland. Vice versa, immigration declines in times of economic difficulty. The graph also suggests that the positive correlation between immigration and GDP growth has been more pronounced since 2002 than in the previous period – hence in the period before the introduction of the free movement of people. This shows that not only is immigration into Switzerland sensitive to business cycles despite the free movement of people, it is even more sensitive now than its was in previous years.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland