Despite Income Tax Holidays, the Swiss Hardly Worked More

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

Do we work more when it pays off? Not necessarily, as a new study by Isabel Martìnez, Michael Siegenthaler and Emmanuel Saez shows. On the basis of Swiss data, the authors demonstrate that a temporary total exemption from income tax has not really resulted in increased labor input.

Do people work more when their wage is temporarily higher? Macro-economists believe that they do and that this is a key driver of employment fluctuations. While working more when your wage is higher makes sense theoretically, can you do it in practice? Many people have jobs with fixed hours and may not be able to switch jobs easily. People have careers where harder work does not immediately translate into higher earnings. Those out of the labor force might not be able to find jobs quickly. So how do temporary tax changes affect the macroeconomic labor supply?

The Swiss income tax holiday

In a recent study (Martínez et al, 2018), Isabel Martìnez, Michael Siegenthaler and Emmanuel Saez break new ground on this important question by documenting the labor supply decisions of the entire Swiss population during an exceptional tax experiment: a massive, temporary increase in workers’ after-tax wages caused by one- to two-year long income tax holidays. During the tax holidays, earnings were fully exempted from income taxation––the average tax rate fell from around 11% to zero. The marginal tax rate fell from more than 20% to zero. The holidays thus created large incentives to work more in the tax-free years.

The tax holidays were a peculiar side effect of Switzerland’s change from a past-oriented tax system to a modern pay-as-you-earn tax system. To avoid double taxation, income earned during the transition had to be exempt from taxation so that people would not pay taxes both on past incomes (as in the old system) and on current income (in the new system). Interestingly, not all Swiss cantons transitioned at the same point in time. Two cantons had a tax holiday for years 1997 and 1998; 16 cantons had a tax holiday for years 1999-2000; four cantons had a tax holiday in 2000 only; and three cantons had a tax holiday for years 2001-2002.

Surprisingly small labor supply effects despite large incentives

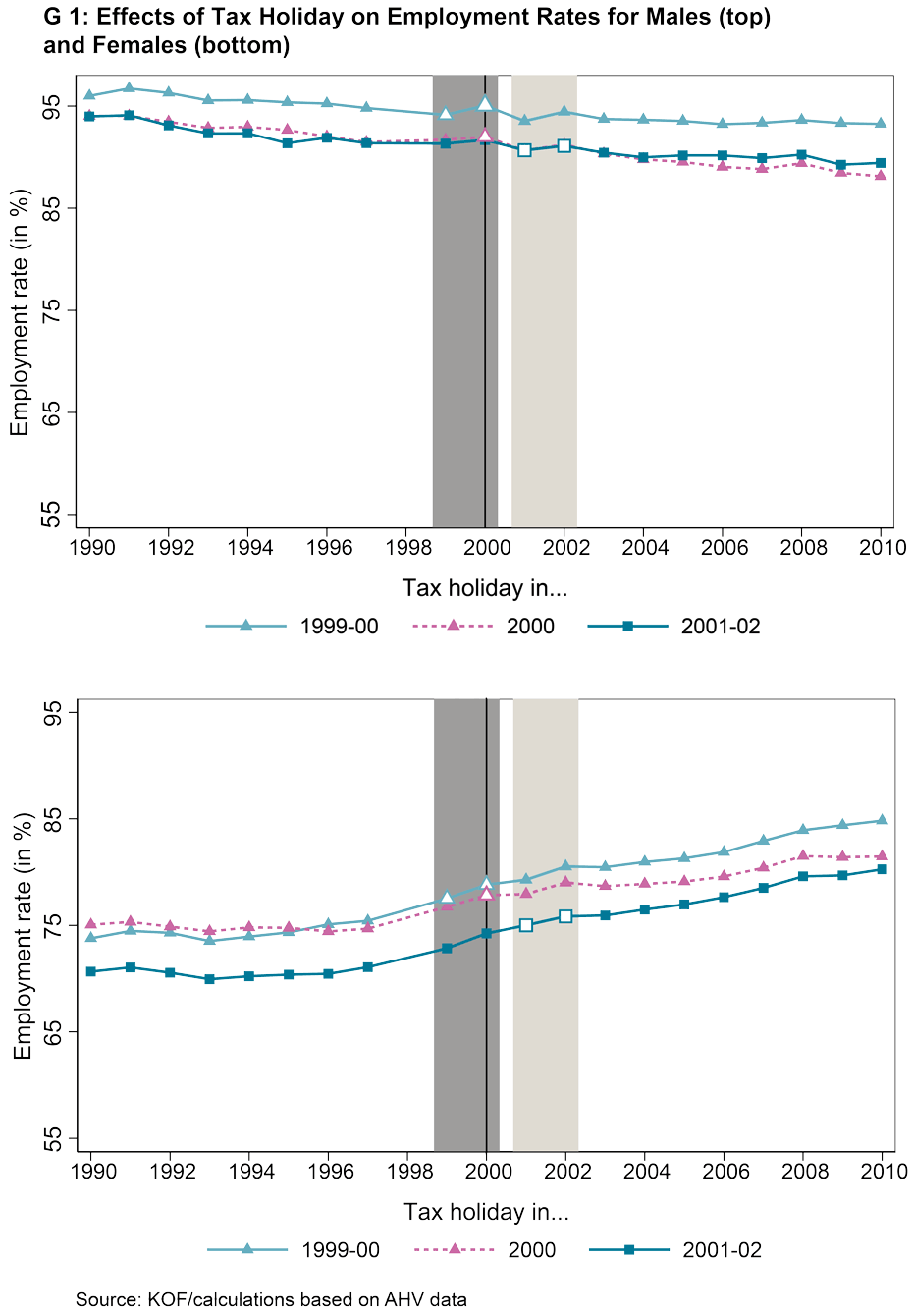

Did the zero tax burden during the holidays affect workers’ decisions whether or not to work? This question is studied in Figure 1 using population-wide social security earnings records matched to 2010 Census data. The figure displays the share of employed men (top panel) and women (bottom panel) in the total population aged 20-60 from 1990 to 2010. For the purpose of this column, these employment rates are only shown for three groups of cantons: 16 cantons with a tax holiday in 1999 and 2000 (in light green); four cantons with a tax holiday for 2000 (in darker green); and three cantons with tax holiday in 2001-02 (in brown). The employment rate is the fraction of individuals in the sample with positive labor earnings during the year.

Overall, there is surprisingly little evidence that the large drop in taxes affected the labor supply of the average worker in the population although workers had one or even two years to adjust. The authors find no evidence of a response along the employment, not even for subgroups usually considered to react more strongly along this margin, such as married women. The evidence suggests that people cannot easily adjust their labor supply to take advantage of the tax holidays. Therefore, the intertemporal labor supply responses appear to be very small on average at the macro-economic level. Some groups however, such as high earners or the self-employed, can take advantage of the tax holidays by artificially shifting their income into the tax holiday. This evidence of small real labor supply responses overall with large tax avoidance responses for specific groups who can avoid taxes is very consistent with the large literature on behavioral responses to income taxation.

Implications for Macroeconomics

Although this may not seem obvious at first, these results have important implications for macro models used to understand employment fluctuations during the business cycle. The reason is that the results identify a key parameter in these models: the so-called Frisch elasticity, which measures workers’ willingness to work more if the wage increases temporarily. The parameter is important in business cycle models because it governs the extent to which the models can match an important fact about business cycles: that recessions lead to large falls in employment but to only limited reductions in wages. If the Frisch elasticity is large, workers labor supply decisions can explain this fact: even a relatively small wage decrease in a recession induces workers to leave the labor force voluntarily. Comparing the prevailing wage with the gains from enjoying leisure time, they decide to abstain from participating in the labor market. The results suggest that voluntary withdrawals do not play an important role in explaining employment reductions during recessions. Indeed, the Frisch elasticities that the authors estimate are orders of magnitude smaller than the Frisch elasticities that many macro business cycle models require to match the employment reductions during recessions.

Literature

Martìnez, Isabel, Michael Siegenthaler, und Emmanuel Saez (2018): Intertemporal labor supply substitution? Evidence from the Swiss Income Tax Holiday, NBER Working Paper No. 24634.

Note

external page Note: On Ökonomenstimme and Vox you can read a detailed version of this article.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland