Five Insights About Wages in Switzerland

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

Although the Swiss economy went through a difficult phase in 2015 and 2016, real wages grew relatively substantially during this period, only to drop again in the subsequent two years. This development provides five key insights into wage setting in Switzerland.

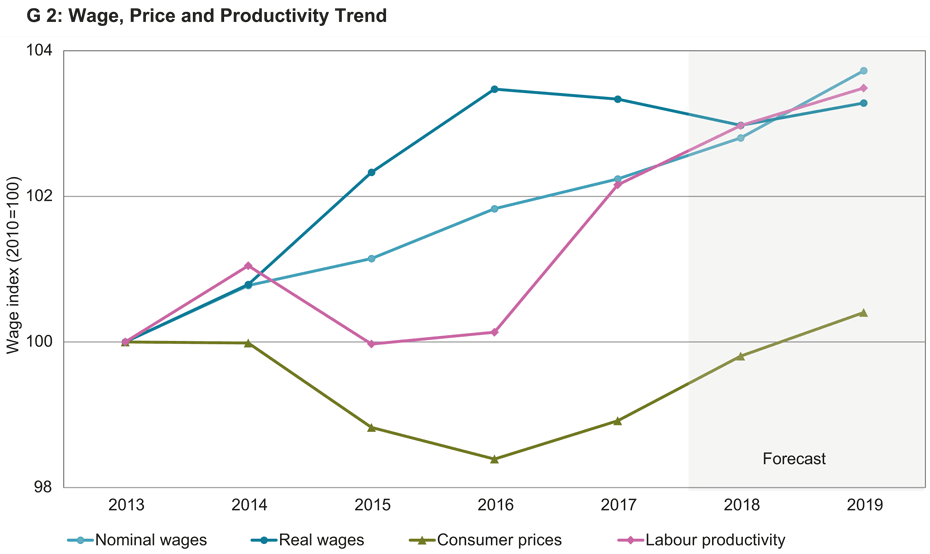

Although wages have declined in the last two years after deduction of inflation, they had been growing rather substantially in the preceding three years. The following graph (see G 2) illustrates this to and fro, showing the development of real and nominal wages, consumer prices according to the National Consumer Price Index (CPI) and labour productivity. All in all, real wages according to the Swiss Wage Index rose by around 3% between 2013 and 2018. Labour productivity recorded a similar gain. This is no coincidence since labour productivity is by far the most important long-term driver of wage growth.

The graph also shows that nominal wages rose rather evenly throughout the four-year period under review, while the trend in real wages was anything but constant. In the years 2015 and 2016, real wages recorded a relatively significant increase, followed by a decline in the two subsequent years. At first glance, this may seem surprising given that neither 2015 nor 2016 were easy years for the Swiss economy due to the Swiss franc shock.

The main reason for the substantial rise in real wages in these years was the unexpected drop in prices in 2015 and 2016. In 2015, for instance, prices of consumer goods in Switzerland came down by more than 1%. The leading cause for the falling prices was the suspension of the minimum exchange rate between the Swiss franc and the Euro, which resulted in the Swiss franc shock. Thanks to this revaluation, consumer goods from abroad became much cheaper in Swiss francs. As a result of lower prices, even those wage earners whose contractual wages did not change were able to afford more goods and services.

Little room for wage increases

The tables turned in 2017 when consumer prices started rising again. Although the business situation of Swiss companies improved gradually, many enterprises had little leeway for wage increases. In order to retain their customers, many exporters did not change their prices in Euro after the Swiss franc shock, although their prices slumped in francs. As a result, costs rose in relation to revenues. Due to lower margins, there was no money for investments in machinery and R&D. With numerous companies catching up on investments before granting higher wages, few employees received any wage rises in 2017 and 2018. By then, rising prices were once again putting pressure on consumer finances. As a consequence, real wages declined two years in a row. Prospects for wage earners are likely to remain gloomy in the coming year: According to the winter 2018 economic forecast, wages after deduction of inflation are unlikely to rise substantially in 2019.

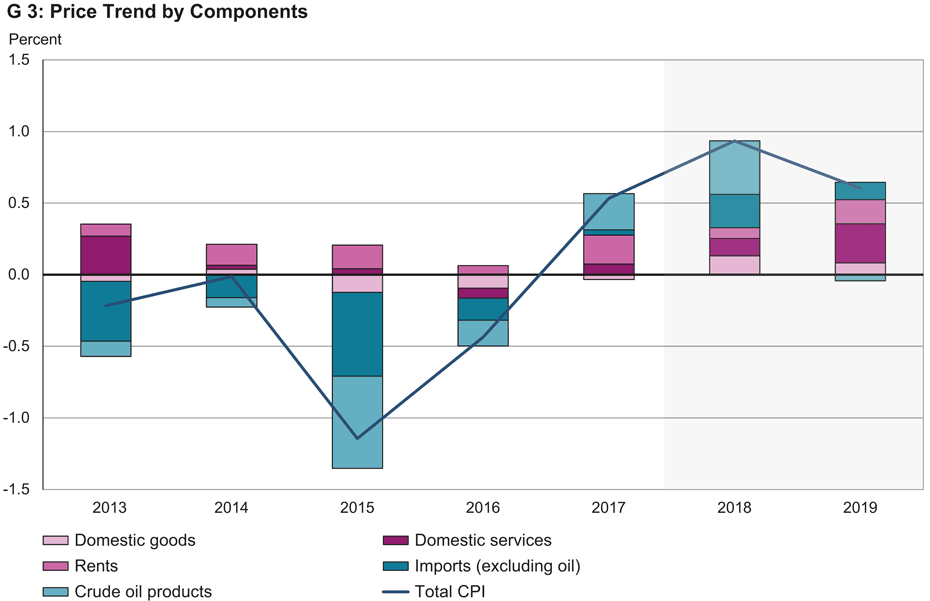

These observations show that the wage trend in Switzerland was largely dominated by the trend in consumer prices in the last few years. The following graph (see G 3) illustrates that the decline in prices was, in turn, driven by the exchange rate trend.

In 2014, the average price level was similar to the year before. However, due to the unexpected suspension of the minimum exchange rate, prices came under pressure in early 2015. Prices of both imported and domestic products declined substantially in 2015. This trend was reinforced by the international commodity price development. Compared to the preceding year, the price of crude oil on the global markets almost dropped by half in 2015. At -1.4%, annual inflation dropped to the lowest value of the century in August 2015. The price level of domestic goods also fell significantly within the space of a year (-0.5%), driven down by rising competition from abroad. Both domestic private and public services and domestic goods became cheaper.

2016 was also dominated by the Swiss economy’s adjustment to the Swiss Franc revaluation. Although the effects of the revaluation on imported goods started to peter out, increased competition from abroad pushed the entire average domestic inflation rate below zero. This was a new phenomenon in Switzerland. All in all, prices remained 0.4% below the previous year’s level. In early 2017, inflation climbed back above zero. Among other reasons, this was due to a stronger global economic trend and a prolonged stable exchange rate that lost considerable ground in the second half of the year. On top of this, prices of imported goods slowly began to recover and the rising global economic dynamics pushed up the price of crude oil. Hence, the dynamics of the last few years had finally reversed. For the first time since 2010, annual average inflation had climbed above zero again. This trend continued in 2018.

Analysis of the last few years shows that inflation was mostly dominated by two rather unpredictable factors: the price of crude oil and the development of the Swiss franc. Hence, for some wage earners, the 2015 Swiss Franc shock practically came as a belated Christmas present as the purchasing power of their wages went up significantly without any effort on their part.

All in all, a lot can be learned from the trend in Swiss wage setting in the last few years. Here are five insights.

1. Unexpected changes in consumer prices determine the trend in the wages’ purchasing power

As in other countries, wage negotiations in Switzerland focus on nominal wages, not real wages. It is true that inflation is included in the wage negotiations since unions or employers ask for inflation adjustments. However, if there are surprise changes in prices, as with the Swiss franc shock in 2015, the trend in real wages may deviate substantially from the trend in nominal wages. Hence, the risk of changes in consumer prices is borne by the wage earners.

2. Wages are adjusted to past inflation instead of future inflation

During wage negotiations in Switzerland, wages are predominantly adjusted to past inflation although it would make more sense to link wages primarily with expected rises in consumer prices.

3. The reaction of wages to cyclical fluctuations is weak and delayed

The economic trend affects wage growth in Switzerland, albeit to a moderate degree. The GDP fluctuates much more than nominal wages, which have gone up rather consistently in the last few years despite cyclical fluctuations. One reason for this delay is the fact that wage negotiations in Switzerland usually take place only once a year, in autumn. If an unexpected economic slump occurs thereafter, as in the case of the Swiss franc shock in January 2015, this will not be reflected until the wage agreements of the following autumn. One key exception to this rule are the wages of new employees, which react sooner and more substantially to cyclical fluctuations.

4. Nominal wage cuts in Switzerland are minor even in difficult phases

Companies in Switzerland are very restrained when it comes to lowering the contractual wages of their employees. This was even true after the Swiss franc shock, despite the fact that the latter significantly affected the competitiveness of many companies. This raises the question what actually holds companies back from cutting their employees’ wages. One key reason is probably the negative effect of wage cuts on staff morale and the potential departure of top employees.

5. In the long run, real wages grow in line with labour productivity

On a long term basis, wages in Switzerland rise precisely in line with labour productivity. If wages rose faster than labour productivity over a longer period of time, wage earners could secure an ever growing slice of the macroeconomic pie. Nevertheless, in Switzerland, this slice has been surprisingly constant. In the short term, however, the macroeconomic productivity and wage trends may well deviate from each other as during the Swiss franc crisis, when wage earners practically lived above their means – especially in 2015 and 2016.

This text appeared as a guest contribution in external page «Lohnbuch Schweiz 2019» (Swiss Wage Book) (in German) published by the Office for Economy and Labour of the Canton of Zurich.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland