Do Internships Really Pay Off?

- KOF Bulletin

- Vocational Education and Training

Increasing numbers of university students do internships during their time at university to prepare themselves for the labour market. However, there is little evidence whether or not such an investment actually pays off. A new study investigates this question.

Why do young people do internships during their time at university? According to human capital theory, students acquire skills during internships which enhance their productivity (Becker, 1964). The acquired human capital can be of a general nature, focus on a certain field or be exclusively relevant to the firm where the internship took place. The so-called signalling and selection theories (Spence, 1973, Stiglitz, 1975) postulate that internships allow students to reduce information asymmetries in regard of their skills. A third theory assumes that students on internships acquire social capital in the form of networks (Granovetter, 1973).

The question of the effect mechanism is of central importance, especially for policymakers. If the impact is mainly based on a signalling or selection effect, it is less important for universities to promote internships. However, if there is a human capital effect, universities could improve their degrees by giving internships more weight in the curriculum.

Internships increase income in the short and the long run

A current study conducted by KOF researchers therefore investigates the impact university internships have on income one year and five years after graduation. One difficulty associated with such empirical analysis is the fact that the decision in favour of an internship is connected with the personal characteristics of the graduates (e.g. motivation and drive). Information regarding any jobs students may have had alongside their degree may go some way to meet this challenge.

Moreover, an instrumental variable approach can be applied to exploit the differences between universities and fields of study in regard of their mandatory internship requirements. However, it is also possible that students select their university and field of study on the basis of these requirements. This problem can be addressed with an empirical approach that exclusively considers the requirements of the closest university.

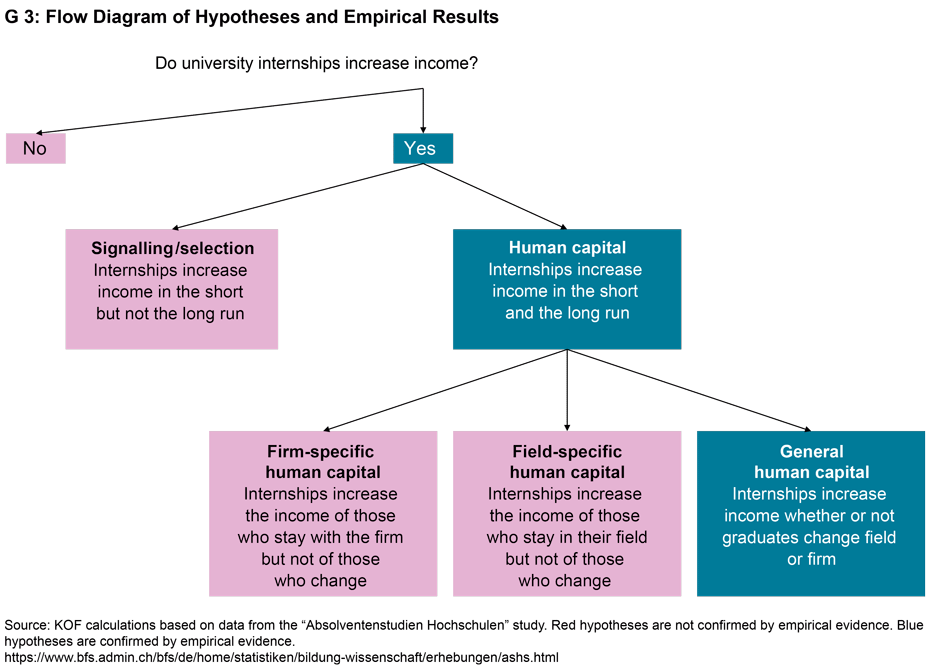

To distinguish between the various effect mechanisms, the applied analysis consists of several steps which are presented in the form of a flow diagram in Graph 3 below. As a first step, the impact of internships on income is analysed for both the short run and the long run (one year and five years after graduation). The results show that internships do increase income and that this impact is still present five years after graduation. The result does not confirm the hypothesis that the impact arises from the signalling of skills or from selection since the impact would then be of a short-term nature. Consequently, the result favours the human capital hypothesis.

Increase in general human capital

It is possible that the accumulated human capital is specific to the firm where the internship took place. To test this hypothesis, income gains are compared between graduates who remain in the firm where they did their internship and those who change to a different company. Since the results do not show any differences between these two groups, the hypothesis of firm-specific human capital is not confirmed.

Even if the human capital acquired during the internship is not of a firm-specific nature, it could still be field-specific. This can be analysed on an empirical basis through comparison of graduates who remain in the same field and those who change to a different field. The results do not show a different impact of internships for those who remain in the same field and those who change. Consequently, the hypothesis of field-specific human capital is also not confirmed.

The empirical results corroborate neither the hypothesis of firm-specific human capital nor the hypothesis of field-specific human capital. This indicates that the human capital acquired during the internship is of a general nature. Such general human capital may for instance consist of social skills, such as ability to work under pressure, ability to work in teams, reliability or commitment.

Universities could do more to promote internships

The results indicate that university internships increase income by enhancing the general human capital. Consequently, universities could do more to promote internships, for instance by giving internships more weight in the curriculum. However, students with work experience may benefit less from additional internships. In this case, universities could give students credits for their work experience.

Literature

Bolli, T., K. M. Caves, and M. E. Oswald-Egg (2019): Valuable experience: How internships affect university graduates’ income. KOF Working Papers, 459.

Becker, G. (1964): Human Capital. New York: NBER.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973): The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Spence, M. (1973): Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1975): The Theory of «Screening», Education, and the Distribution of Income. The American Economic Review, 65(3), 283-300.

Contact

No database information available

No database information available

No database information available