The Swiss Franc’s Equilibrium Exchange Rate: a Tentative Assessment

- Business Cycle

- KOF Bulletin

The turbulent history of the Swiss franc since the outbreak of the financial crisis has increasingly raised the question as to where the point of equilibrium is for the Swiss franc exchange rate. Although there cannot be any absolute point of equilibrium, attempts have nonetheless been made to assess the mispricing of the Swiss franc using the Behavioural Equilibrium Exchange Rate (BEER) model.

In recent years, the Swiss franc has increased in value by around 34% in nominal terms compared to its trading partners. What has driven this upward trajectory in the effective exchange rate? Part of this can be attributed to differences in price trends. Since foreign inflation rates have been higher than in Switzerland in this period, a nominal increase in the value of the Swiss franc compared to foreign currencies has been necessary in order to avoid an increase in price differentials.

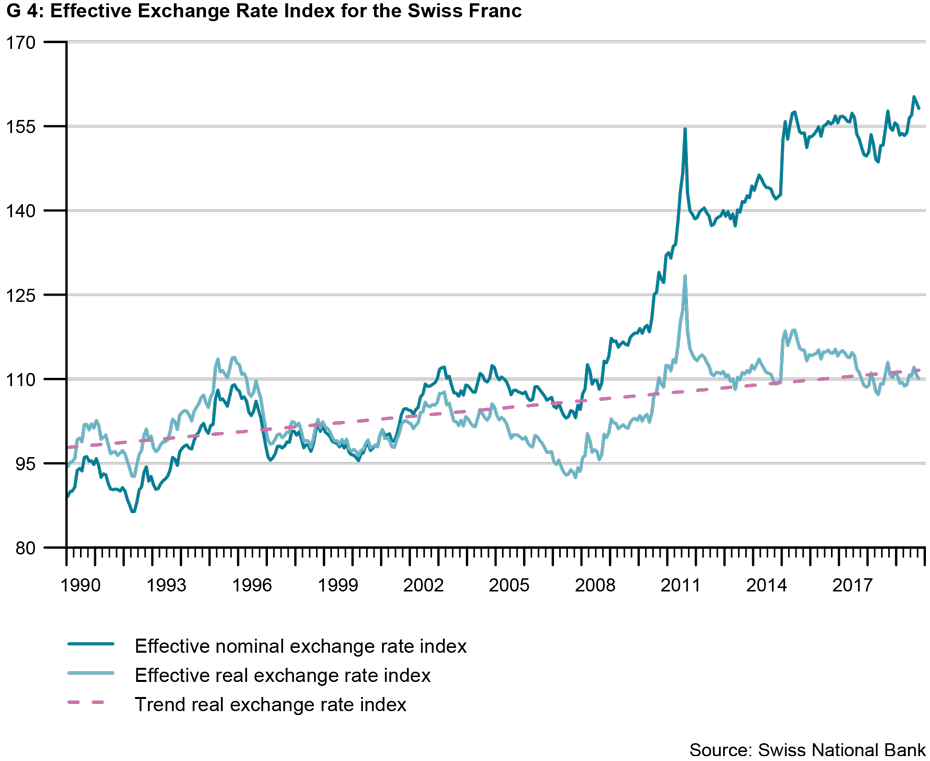

Graph 4 shows the change in the real exchange rate index between the Swiss franc and foreign trade-weighted currencies – i.e. the prices of domestic goods expressed in units of foreign goods. Although the 7% increase in the real exchange rate index over the last decade has been significantly less marked than the rise in the nominal exchange rate index, it is also following an upward trajectory. This means that the changes in the exchange rate must also be driven by other factors.

Which factors have had an influence on the exchange rate?

A KOF researcher has investigated which factors have impacted upon the exchange rate in recent years. The purpose of the Behavioural Equilibrium Exchange Rate (BEER) model is to estimate the correlation between fundamental factors in one country relative to another country along with the real exchange rate between the currencies of the two countries (Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2009). The following fundamental factors were considered:

- Productivity: under to the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, prices are high in high-productivity countries. According to the theory of purchasing power parity, high prices mean a strong currency. Productivity was approximated within the applied model using price-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

- Foreign assets: if Switzerland, compared to other countries, has a relatively high level of foreign assets as a proportion of GDP, it will be able to run a balance of trade deficit in future and nonetheless remain solvent. Foreign countries will conversely have to run a balance of trade surplus in future in order to ensure that intertemporal budget constraints are complied with over the long term. Switzerland is relatively wealthy thanks to its positive level of foreign assets; as a result, Swiss demand for goods is strong and Swiss goods have high prices. The high prices or inflated real exchange rate makes Swiss goods less competitive and therefore facilitates the achievement of a balance of trade surplus by foreign countries with Switzerland (Lane und Milesi-Ferretti, 2002; Mancini Griffoli et al., 2015).

- Real interest rate difference: a positive real interest rate differential with foreign countries will result in an increase in the value of the domestic currency. This is because capital flows from the low-interest country into the high-interest country with the result that demand for the high-interest country's currency increases.

- Terms of trade: the terms of trade show changes in the rate of exchange between exports and imports by dividing the price index for exported goods by the price index for imported goods. If the prices for exported goods relative to imported goods in Switzerland increase more strongly than abroad, Switzerland will achieve a welfare gain because more goods can be imported in return for a given quantity of exported goods. This additional income raises demand for tradable and non-tradable goods, which has a positive effect on the real exchange rate.

- Government spending: since the state consumes non-tradable goods in particular, any increase in government spending as a proportion of GDP in Switzerland compared to abroad will lead to increased demand for those goods, and hence an increase in their prices. This causes the real exchange rate to rise.

- Openness to trade: the openness to trade represents the sum total of exports and imports of goods and services as a proportion of GDP. If a country pursues a liberal trade policy, prices for domestically produced tradable goods are relatively low. This is associated with an increase in the value of the real exchange rate.

Factors that are not fundamental include, for example, monetary inflows triggered by the Swiss franc’s status as a “safe haven” or foreign exchange purchases by the Swiss National Bank. The reason for this is that these variables do not influence the fair value of the Swiss franc.

The overvaluation dynamic seems to have been ongoing since 2010

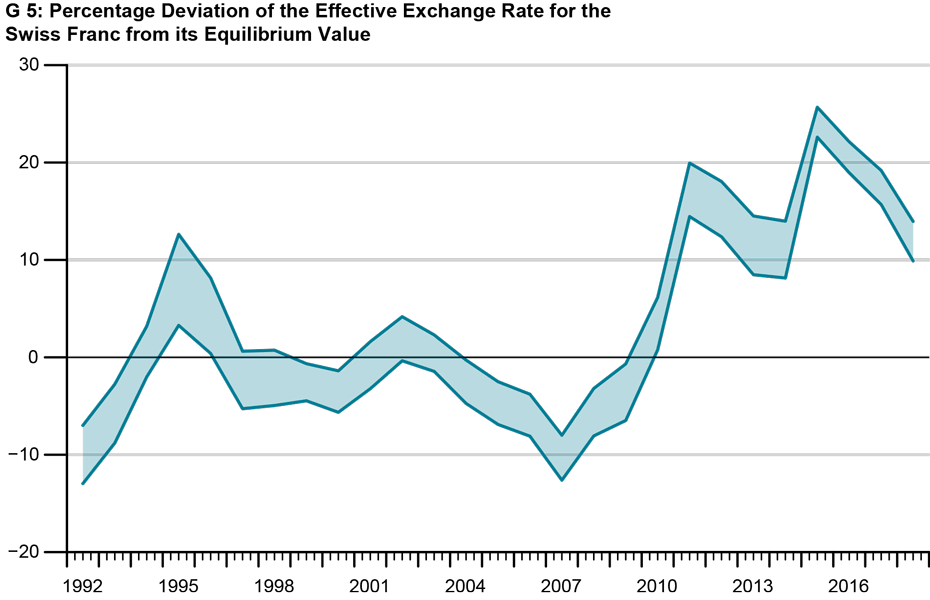

The equilibrium exchange rate can be established with reference to the coefficients estimated. Figure 2 shows the percentage mispricing of the Swiss franc compared to its trade partners as an area within which the values calculated fall. Positive mispricing means that the Swiss franc is overvalued.

The results suggest that the Swiss franc was undervalued between 2004 and 2009. From 2008 onwards, the undervaluation ended abruptly and turned into an overvaluation in 2010. Since then, the equilibrium exchange rate has not been re-established. The breadth of the mispricing calculated for 2018 is between 10% and 14%. Equilibrium exchange rates are highly sensitive to the variables used and the countries sampled. For this reason, the results have to be interpreted with caution.

The model also enables the variables that drive the exchange rate to be identified. In recent years price-adjusted GDP per capita has had the greatest influence, followed by foreign assets in second place. Both of these variables have a greater impact in Switzerland than in foreign countries, and have thus been drivers of the strong Swiss franc. The third most important variable is the real interest rate, which is relatively low in Switzerland and has thus had the effect of weakening the value of the Swiss franc. The other three variables are less significant.

Literature

Bénassy-Quéré, A.; S. Béreau, and V. Mignon (2009) : Robust estimations of equilibrium exchange rates within the G20: A panel BEER approach. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 56(5):608-633.

Lane, P. R. and G. M. Milesi-Ferretti (2002): External wealth, the trade balance, and the real exchange rate. European Economic Review, 46(6):1049-1071.

Mancini Griffoli, T.; C. Meyer; J.-M. Natal, and A. Zanetti (2015): Determinants of the Swiss franc real exchange rate. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 151(4):299-331.

Contact

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland