Swiss Internal Tax Competition and Inequality

- Fiscal Policy

- KOF Bulletin

Recently, there has been lively debate about Switzerland’s role in international tax competition. The author of this article investigates the phenomenon of ‘socio-spatial segregation’, one of the effects of inter-cantonal tax competition. ‘Socio-spatial segregation’ refers to the geographical concentration of households which are similar in terms of criteria such as income, wealth, age or ethnicity.

Does so-called ‘tax competition’ at the cantonal and municipality level favour public services à la carte? Cantonal tax autonomy and diverging tax rates in different localities have always been the rule in modern Switzerland. However, when taxpayers’ mobility was still low, diverging tax rates did not translate into competition for ‘good’ taxpayers. Proper tax competition which pursued this aim only began in the 1990s. This competition is often seen as one of the elements of the Swiss success story.

According to this view, there is a market on which local authorities determine the type and scope of their public services as well as the associated prices, i.e. tax rates and tax multipliers. Based on their preferences, residents decide which price they are willing to pay for specific types of public services and choose their domicile accordingly. Competition between the cantons and municipalities ensures that the public services are provided at a ‘competitive’ price according to the residents’ preferences.

However, the market analogy is not entirely accurate since Swiss residents are not ‘representative agents’ who distinguish themselves exclusively in regard of their public service preferences; they also differ in terms of income and wealth. Furthermore, cantons and municipalities predominantly provide public goods for which there are no markets or prices. And finally, a large portion of the expenditure of the Swiss cantons and municipalities consists of transfer payments, such as premium reductions and social benefits paid to the less well-off, which do not directly benefit those who pay for them. Hence, equivalence of payments and benefits is not given. In a progressive tax system such as Switzerland's, the resulting incentive to contribute as little as possible to the benefits provided by the public authorities rises disproportionally in relation to income and/or wealth.

Competition for ‘good’ taxpayers

As a result, cantons and municipalities have been competing for ‘good’ taxpayers, especially when it comes to natural entities’ income tax. Since tax considerations have the biggest impact on residence decisions made by those who are considerably better off, the latter are the focus of the study.

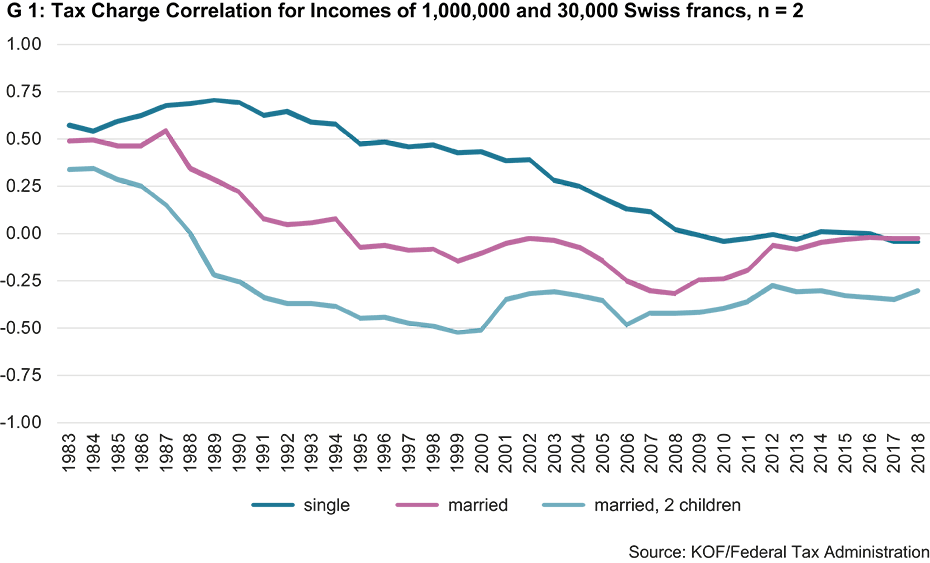

Once the social segregation that has thus been triggered sets in, such segregation tends to potentiate itself. Since the better-off do not qualify for income-related social transfers, tax income rises faster than expenditure, facilitating reductions of tax rates and tax multipliers. This is only true for high incomes; at the lower end there is no ‘competition’. Looking at the income tax paid by households with gross incomes of CHF 30,000 and CHF 1 million in the 26 cantonal capitals, Graph G 1 shows a striking trend in the correlations between the two variables between 1983 and today. Before the onset of tax competition, the correlations were significantly positive throughout, just to diminish rapidly in the late 1980s. They were, and still remain, significantly negative for ‘ideal-type’ single-earner families with two children, while declining towards zero for married couples and singles without children.

This means that, 35 years ago, the less well-off paid comparatively lower taxes in the cantons which also imposed lower taxes on the better-off (and vice versa), while, today, this is not the case at the lower end of the income distribution in cantons with comparably attractive tax rates for top incomes. For families with children, the opposite is true.

Increased segregation of the population

On top of this, the cost of housing is higher in areas where the better-off live. The resulting effect is equivalent to incentivisation: The better-off opt for towns which charge lower tax bills than their places of origin. The situation is different for the less well-off. With housing costs taking up a significant portion of their income, these costs determine how much is left after deduction of health insurance premiums and taxes. For these households, rising housing costs are thus an incentive to move to less expensive towns, especially since this has little effect on the households’ tax bills. Such relocations are not always voluntary as authorities set housing benefit ceilings and exert more or less gentle pressure on social benefit recipients to move elsewhere. The author of this article refers to this phenomenon as the ‘dark’ side of inter-cantonal tax competition.

The result is desegregation of the population: While the better-off are concentrated in locations with low tax rates for top earners and ample tax income combined with low expenditure for social transfer payments, the less well-off are concentrated in locations with high tax rates in the highest progressive tax brackets and low tax earnings combined with high expenditure for social transfer payments.

Financial equalisation limits impact of tax competition

The data presented by the author fit this picture. Lower tax rates for top incomes go hand in hand with high average taxable income at the cantonal level as well as high housing costs (with the exception of Geneva), and a comparably low incidence of poverty. Hence, the less well-off are concentrated in areas where the better-off incur higher tax rates. Since tax competition and its consequences occur both at the cantonal level and at the inter-cantonal municipal level, the above findings are more likely to underestimate the correlations than overestimate them.

There are different aspects to the effects of tax competition. What may make sense at the individual level (choice of domicile according to financial aspects) is dysfunctional at the social level. Consequently, financial equalisation at the national level, and at the municipal level in several cantons, aims to alleviate problems which are exacerbated, or created in the first place, by tax competition. In light of this, the question arises whether the posited efficiency gains and productivity growth offset the disadvantages caused by the resultant, demonstrable social-spatial desegregation, and also which population groups benefits from tax competition and which do not. While those who agree with the regulative premise of a ‘streamlined’ state will probably judge in favour, those who prefer a more egalitarian society are likely to find against tax competition.

The full version of this article is available in «KOF Analysen» 4/2019.

Contact

Dep. Management,Technolog.u.Ökon.

Weinbergstr. 56/58

8092

Zürich

Switzerland