Globalisation and Its Impact on the Middle Class

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

A new study shows that globalisation has diminished the income share of the middle class. Even the poorer parts of the population saw their income shares decline, while the shares of high incomes has risen. This effect is driven by developments in transition and developing countries.

Today, it would be hard to imagine the world without globalisation and its far-reaching impact on politics, economy and society. However, research has so far failed to provide any conclusive and consistent results regarding its impact on income and income distribution. In-depth analysis requires more than mere reference to conventional inequality indicators such as the GINI coefficient.

The GINI coefficient mostly changes when the well-off population becomes richer, the poor population becomes poorer or both trends occur. A shift in middle incomes rarely affects the coefficient. It is therefore important to conduct in-depth research into income distributions with a focus on changes in the middle class bracket, as has been done in the present study.

Significant shrinkage of middle class in USA, special case of former socialist states

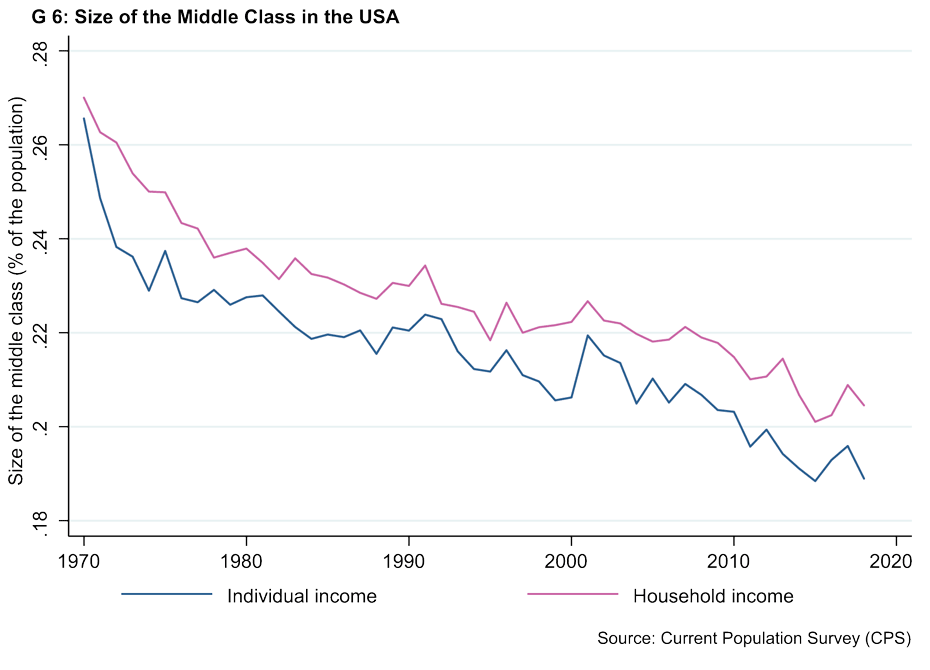

Based on the percentage of middle-income individuals and households, the middle class in the USA has seen a steady decline over a number of decades. In this context, middle income has been defined as any income between 75% and 125% of the median income. The two lines in Chart G 6 show that the middle class in the USA declined substantially between 1970 and 2017, both on the basis of individual incomes and of household incomes. While in 1970, around 27% of the population were part of the middle class, this percentage had fallen to around 20% by 2015.

Another indicator of the size of the middle class is based on the share of middle incomes in the total income of a country. Here, middle incomes have been defined as incomes between the 20th and 80th percentile, or the middle 60%. The share in the total income is calculated by adding together the incomes in this bracket and dividing the sum by the total income. This indicator thus measures the size of the middle class on the basis of its income share instead of the number of individual members.

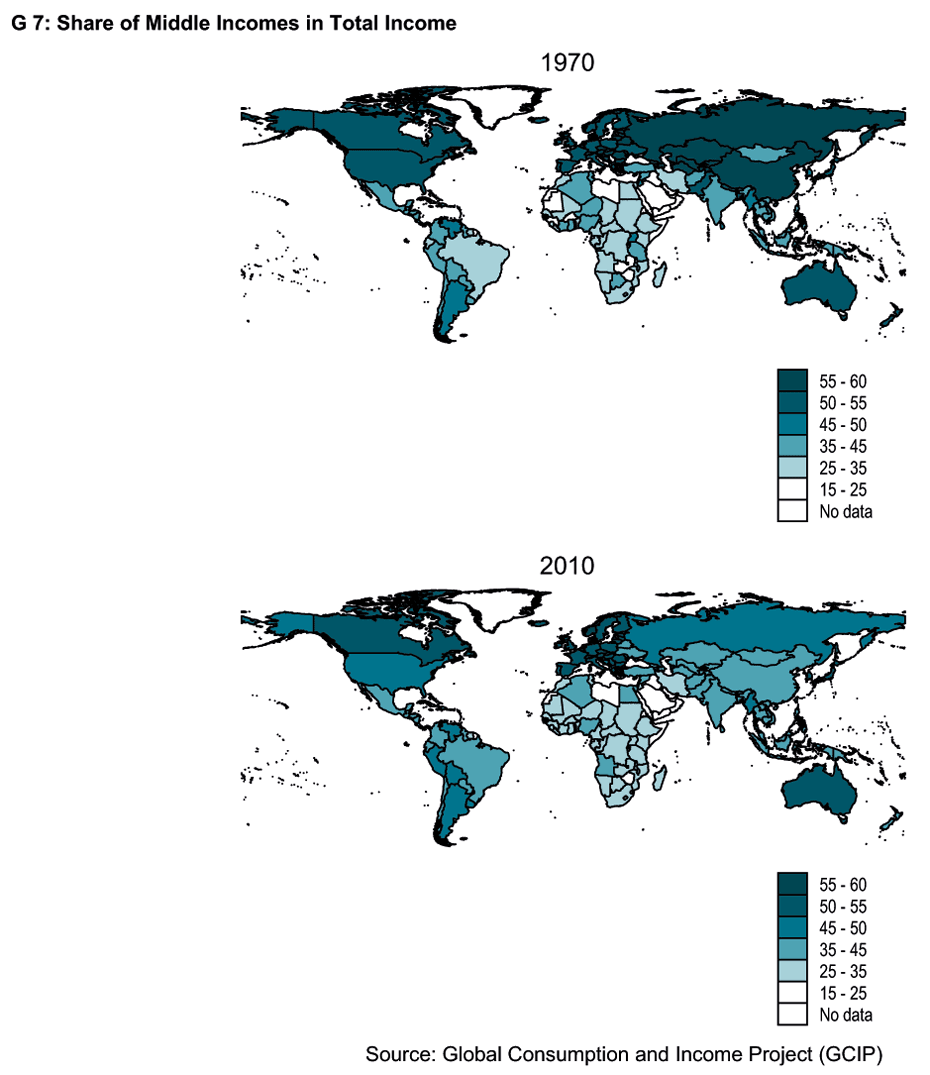

In the context of this indicator, the relative size of the middle class does not change. The worldwide average is 42%. At 50%, Switzerland substantially exceeds the average. The lowest percentages (around 18%) occurred in Burkina Faso and Mauritania in the 1960s. Sweden and Austria recorded the highest percentages (over 55%), also in the 1960s. In the 1970s, percentages in excess of 50% mostly occurred in the former Eastern Bloc countries.

Chart G 7 shows the percentages for the years 1970 and 2010. In general, the percentages have declined over time. However, in Europe, Canada and Australia, the figures have remained relatively stable. The biggest differentials can be found in Asia and Latin America. The former Soviet republics, which showed very high percentages of middle incomes until the breakup of the Soviet Union, represent a special case. Since the breakup, the percentages have been on the decline, especially in the countries bordering Russia, such as Kazakhstan or Ukraine. The USA is also showing a marked drop in the percentage of middle incomes.

Economic globalisation has a substantial impact on the share of middle incomes

Principally, the decline in the income shares of the middle class is due to a number of different reasons. However, according to the data, one specific reason is economic globalisation. This comprises any economic exchange between countries, with a distinction being made between de facto and de jure measures. While de facto measures comprise actual flows, such as imports, exports and foreign direct investment, de jure globalisation measures are associated with regulatory principles, such as import restrictions or financial regulation.

Analysis of 132 countries in the period 1970 to 2014 shows that de facto measures of economic globalisation have a significant impact on the income shares of the middle class. A decline in income shares was measured in the wake of escalating waves of globalisation. However, this effect can be exclusively attributed to actual flows of goods and services. Regulatory changes, for instance the introduction of import duties, do not have any statistically significant impact on income shares and hence on income distribution. This difference is not surprising since an increase in de jure globalisation in the form of reduced regulation may, but does not have to, lead to greater de facto globalisation.

High incomes absorb losses in low and middle income brackets

Further analysis also shows that increased de facto globalisation also leads to income losses among the poorer population, while high incomes record a statistically significant increase. Hence, high incomes absorb the income losses of the low and middle incomes and economic globalisation leads to greater inequality.

Chart G 7 clearly shows that the biggest changes in the shares of middle incomes in the period 1970 to 2010 occurred in lower-income countries. Middle incomes in the developed western countries remained largely unchanged. Consistent with these findings, statistically significant effects of economic globalisation on the shares of middle incomes were only found in the less developed countries. States which the World Bank classifies as middle-income countries recorded more substantial effects than developing countries. This is perhaps due to the marked decline in income shares in the former Eastern Bloc countries and China. Developed countries did not show a statistically significant effect.

The full version of this study is available on the external page Ökonomenstimme website and the KOF website.

Contact

No database information available