First hard figures from the United States

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

The fight against the COVID-19 pandemic is causing severe distortions in goods, labour and capital markets. However, it takes several weeks or even months for the reality to reach official statistics and econometric models. In the US, important basic statistics are published earlier and in more detail than in many other countries. The first available indicators for March confirm scenario calculations that predicted a sharp recession.

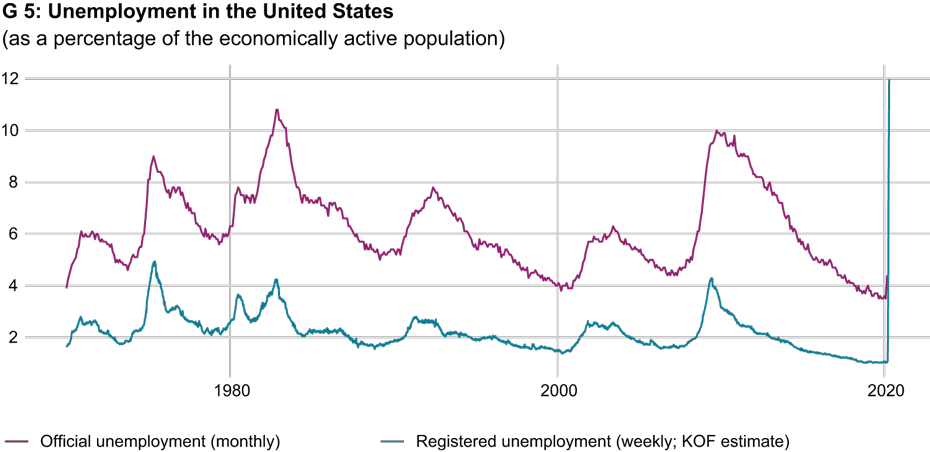

The effects of the containment measures have been seen particularly quickly in the US labour market. Applications for unemployment benefits have risen sharply since the start of the lockdown; at the end of April, almost 20 million Americans made the weekly (virtual) trip to the employment office. This corresponds to around 12 per cent of the labour force (Chart 5). The official unemployment rate is based on surveys and therefore includes, among others, unemployed people who have not registered for benefits. Accordingly, it is usually a few percentage points higher than the registered unemployment rate and is currently likely to exceed 15 per cent. As part of an unprecedented fiscal stimulus, the maximum period for which unemployment benefits can be received has been extended to 39 weeks, while at the same time the eligibility criteria have been relaxed. To this end, unemployment benefit, which varies from $200 to $700 per week depending on the state, will be increased by $600 from state funds.

Sharp slump in car production

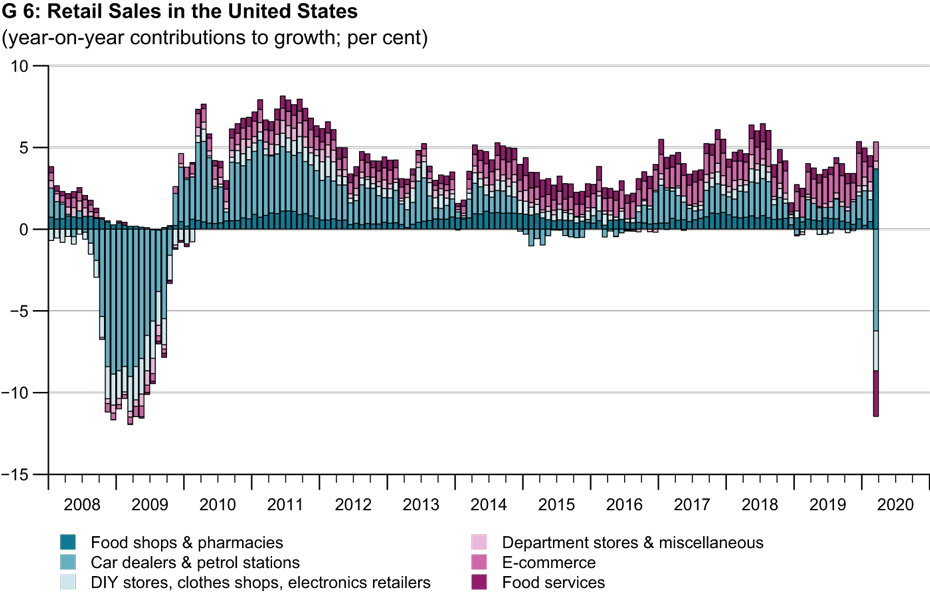

Business closures and social distancing have also turned the consumer behaviour of US citizens upside down. Retail sales in the United States slumped by almost 9 per cent in March compared with the previous month (Chart 6). Electronic equipment (down 15 per cent), car sales (down 27 per cent) and clothing (down 50 per cent) were particularly hard hit. Only sales of food rose significantly (up 27 per cent). Consumer sentiment, as surveyed by the University of Michigan, has deteriorated significantly, reflecting among other things a poorer assessment of the future financial situation of the households surveyed.

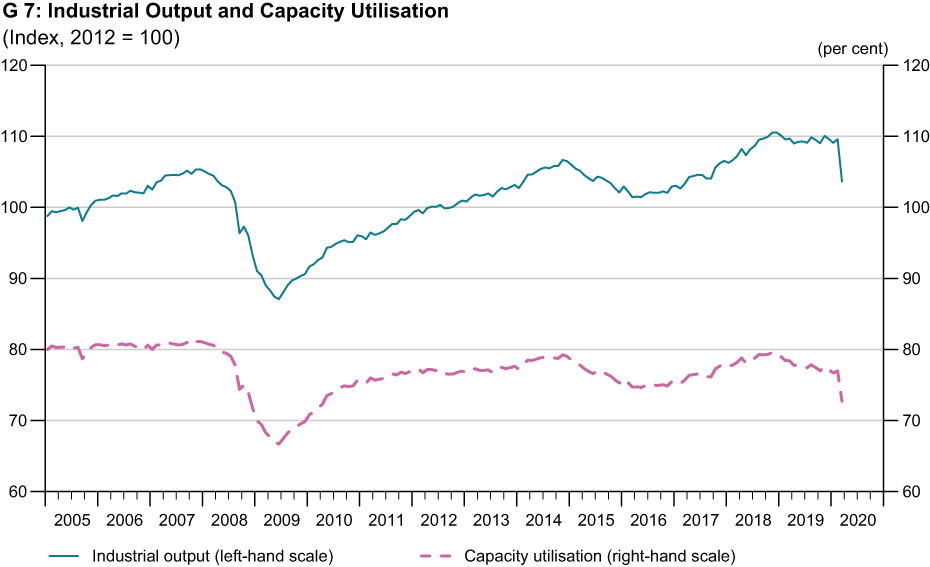

The measures taken to slow the spread of the pandemic are mainly aimed at social interaction and therefore first made themselves felt in consumer-related services. In the meantime, however, the crisis has spread to all sectors of the economy. Industrial production fell by 5.4 per cent in March, and manufacturing output fell by as much as 6.4 per cent (Chart 7). This is the most severe monthly slump since 1946, with the sharpest drop of 27 per cent recorded in the production of motor vehicles. Accordingly, capacity utilisation in industry as a whole fell by almost 5 percentage points to 73 per cent. The major car manufacturers, whose assembly lines have been at a standstill for several weeks, do not plan to resume production until the beginning of May. A further deterioration is therefore to be expected in April.

First flash estimate shows GDP slump

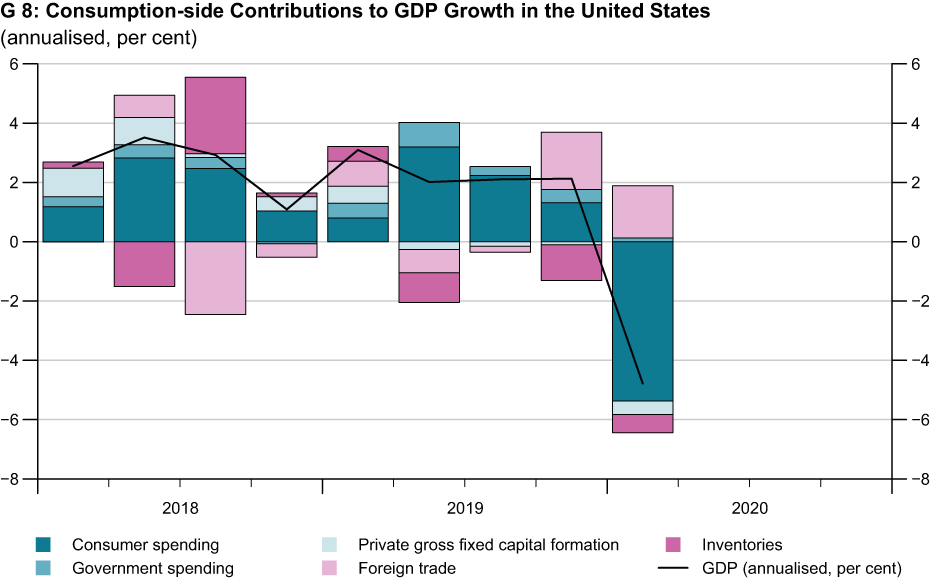

The first flash estimate by the Bureau of Economic Analysis for overall economic production in the first quarter of 2020 also paints a gloomy picture (Chart 8). GDP slumped significantly at an annualised rate of 4.8 per cent. As expected, consumer spending in particular weighed on the economy. Exports and imports also fell sharply, but the bottom line was a positive contribution from net exports. Public spending also had a supportive effect.

This GDP flash estimate is likely to be revised significantly in the coming months in view of the volatile basic statistics. The time lag with which important data are available also involves a high degree of uncertainty for predictions about future economic performance.

However, the difficult data situation is not the only reason why economic forecasts are currently very complex. Econometric models simplify real economic relationships that have existed in the past and extrapolate them into the future. An unprecedented shock like the global COVID-19 pandemic is therefore a major challenge. It forces economists to make strong assumptions and to calculate in scenarios.

In addition, economic forecasts are also dependent on exogenous factors; an example is the duration of the lockdown for various economic sectors. Furthermore, unlike weather forecasts, for example, economic forecasts are also influenced by endogenous factors. These factors come into play, for example, when economic entities change their behaviour and expectations based on the forecasts.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland