What explains the increase in public social expenditure in OECD countries?

- Public Budget

- KOF Bulletin

Almost all industrialised countries now have higher public social spending than they did a few decades ago. How did this increase come about? A recent KOF study shows that globalisation, economic crises, rising unemployment and an ageing population are the main factors affecting social spending. The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to influence future trends.

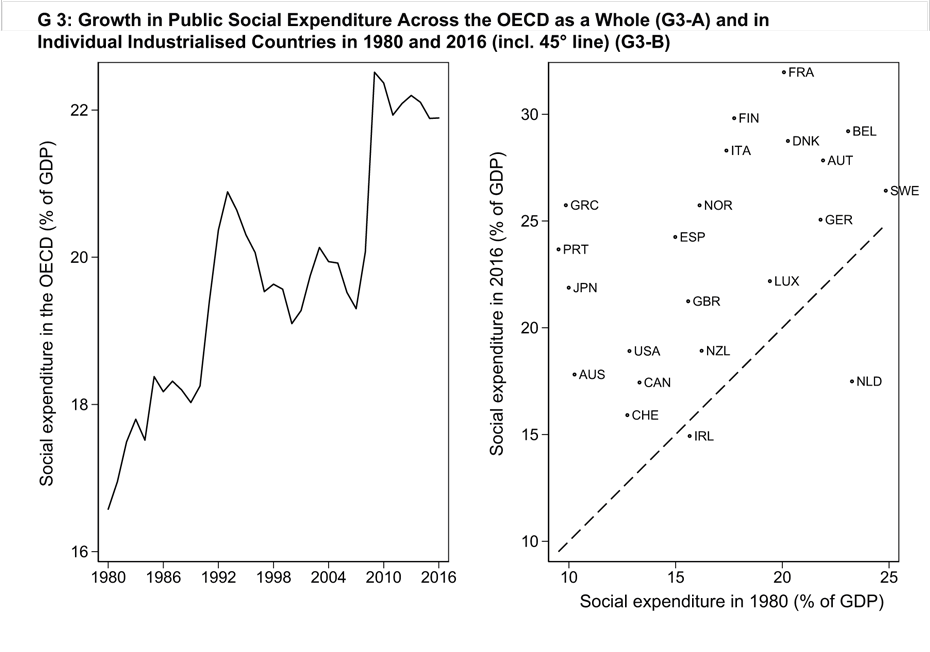

In recent decades, public social spending has risen sharply in industrialised countries. Whereas the social expenditure ratio, i.e. social expenditure as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), averaged 16.6 per cent in OECD countries in 1980, it reached almost 22 per cent in 2016. This increase was particularly sharp in the wake of the financial crisis from 2008 onwards (see G3-A). Even though the size of the welfare state traditionally varies greatly from country to country, growth in public social spending has been observed in almost all industrialised nations. (see G3-B).

Public social expenditure plays an important role in social protection, for example in the event of old age, illness, or loss of employment. In most industrialised countries, social spending is therefore the largest item of expenditure in the public finances. However, rising social expenditure can crowd out other expenditure items if revenues remain constant. This is a condition that commentators have called ‘social dominance’.

What explains the rising social expenditure ratio in industrialised countries, and what factors are responsible for the varying size of the welfare state in different countries? Economic research discusses a variety of determinants. These include economic and demographic factors such as the business cycle or the ageing of a society, but also the effects of globalisation or political-institutional factors such as a country’s governance system or the party-political composition of the government.

A variety of determining factors

A recent KOF study summarises all of the different determinants of economic research and uses statistical methods to identify the robust determinants of public social spending.

The economic determinants include the impact of the business cycle. For example, the social expenditure ratio rises in recessions as economic output declines while higher unemployment increases the need for public welfare benefits. Demographic factors – and, therefore, longer-term factors – include an ageing population, which is associated with rising pension entitlements.

Globalisation also has an impact on public social spending. Some theories conclude that globalisation reduces such spending. This happens when increased tax competition between countries as a result of globalisation reduces tax revenues, which can ultimately lead to lower government spending, including in the social sphere. Globalisation has a positive effect on social spending when a country's electorate demands higher levels of public support and income distribution in order to be better protected from the increased competition resulting from globalisation.

A large body of literature, in turn, refers to a country’s political and institutional framework. The party-political composition of a government can play a role in the level of social spending because left-wing parties traditionally prefer a more comprehensive welfare state than right-wing parties do. The theory of political budget cycles, on the other hand, shows that politicians raise government spending before elections to ensure that they are re-elected. Citizens’ political participation can also have an impact on social spending because, as participation increases, marginalised voters who benefit from an expanded welfare state tend to go to the polls.

Finally, the economic policy framework may also explain why public social spending varies between countries and over time. For example, strict fiscal rules such as a debt brake, conditionality imposed by supranational institutions, or rising debt can slow down any expansion of government spending, including in the social sphere.

Spending is determined by external – and other – factors

An extensive literature review of the determinants of public social spending has enabled 30 variables to be identified. Further variables are added if potential interaction effects are considered. The data set used covers the years from 1980 to 2016 for 31 OECD countries. The robust determinants of public social spending are identified using extreme value analysis and the Bayesian average method (see the box entitled 'Methodology').

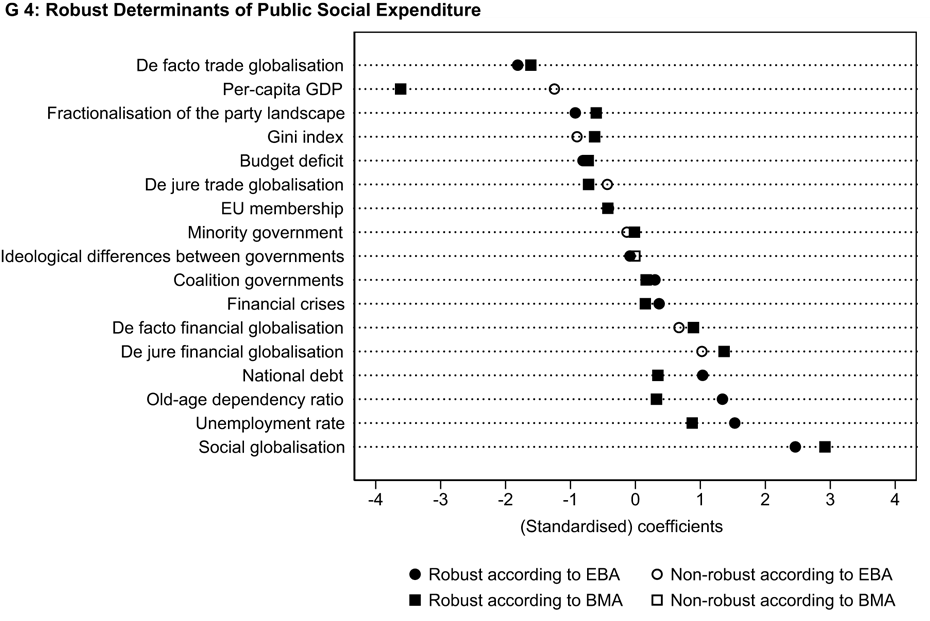

The results show that globalisation, economic crises, rising unemployment, ageing populations and a number of political-institutional factors in particular have an impact on public social spending. For example, the variables for trade globalisation, the fractionalisation of the party landscape and budget deficits correlate negatively with social spending. The variables for coalition governments, financial crises, the national debt, ageing populations, the unemployment rate and social globalisation correlate positively with social spending (see G 4). For example, an increase in the measure of (de facto) trade globalisation by one standard deviation is, on average, associated with a rise of almost 2 percentage points in the social expenditure ratio. On the other hand, an increase in the measure of social globalisation by one standard deviation is, on average, accompanied by a rise of 2.5 to 3 percentage points in the social expenditure ratio.

The results show that the high social expenditure ratio in many countries depends to a large extent on factors which seem to be exogenously predetermined for policymakers in a particular country. These include economic crises as well as longer-term phenomena such as the ageing of society and the effects of globalisation. Consequently, social spending can be expected to increase significantly even in the context of the current pandemic. Despite these external determinants, however, the results also show that policymakers still have the ability to influence a country's social policy by introducing domestic measures.

A full version of this study can be found here.

Methodology

The extreme bounds analysis (EBA) and Bayesian model averaging (BMA) methods are used to identify the robust determinants. Both methods estimate all possible model combinations with the explanatory variables identified above, with the social expenditure ratio as the dependent variable. This high number of estimated model combinations allows the distribution of the estimated coefficients of each explanatory variable to be examined as a second step. Under the extreme value analysis method, for example, a variable is identified as a robust determinant if at least 95 per cent of all estimated coefficients have the same sign.

This statistical analysis identifies 17 of the 30 variables that are considered robust determinants according to either method. Of these, nine of the variables identified are considered robust by either method. Chart G 4 shows the average of the coefficients across all estimated models for the variable identified as robust by one method. The coefficients are standardised with the standard deviation of the explanatory variables so that they can be compared with each other.

Contact

No database information available