What does a higher national debt mean for Switzerland?

- Public Finances

- KOF Bulletin

The coronavirus crisis is causing Switzerland’s national debt to rise. There is already vigorous debate about how to respond to this increase. However, Swiss public finances are still in good shape even in the wake of the crisis. Calculations show that the country’s debt ratio should fall relatively quickly even without fiscal austerity.

The pandemic has caused dramatic collapses in economic activity worldwide and, in some cases, massively higher government spending. As a result, gross public debt as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) has risen sharply in many countries.

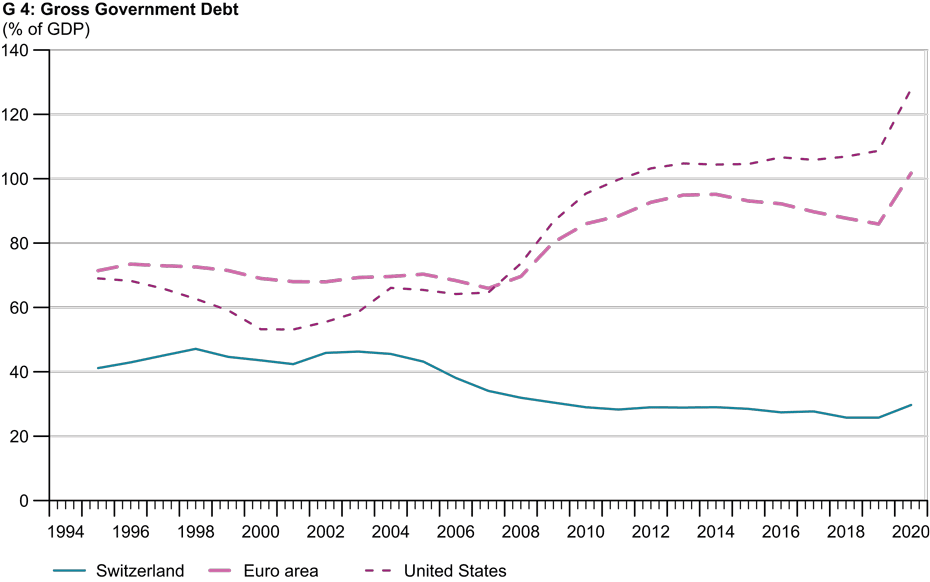

At the end of September the Swiss government expected the country’s debt ratio to increase by 3.4 percentage points (pp) from 25.8 per cent in the wake of the crisis.1 In October, KOF estimated that the Swiss government’s debt ratio would increase by 4.5 pp as a result of the pandemic. Compared with the euro area, where an increase of almost 16 pp is expected in 2020, and the United States, where a rise of over 19 pp is expected, Swiss public finances are in a fairly comfortable position (see Chart G 4).2

The second wave of the pandemic is preventing the increase in Switzerland’s debt ratio from being forecast more reliably. But even if it were to rise by 10 pp or – if things were much worse than currently expected – by as much as 20 pp, debt ratios of just over 35 per cent or even 45 per cent in the wake of the crisis would still be extremely low by international standards.

When government debt becomes problematic

Nevertheless, there is a lively debate in Switzerland on whether and, if so, how to respond to the crisis-related growth in public debt. Some actors in the spheres of politics and business are of the view that the national debt should be reduced as quickly as possible after the crisis. But does this higher nominal debt really have to be brought down swiftly? From an economic perspective this demand is not a compelling one.

Economists consider public debt to be particularly problematic when it is denominated in a foreign currency, so the debt increases when the domestic currency depreciates (the so-called ‘original sin’ of public debt). This is not the case in Switzerland.

Secondly, there is also agreement that the public debt ratio must not be allowed to rise permanently, because then the state's room for manoeuvre would be increasingly constrained as a result of the growth in debt service relative to the tax base. However, there is no consensus on the acceptable level of this ratio. A maximum of 60 per cent is politically desired in the euro area. Empirical research often cites values of around 80 per cent as an upper limit that can be tolerated, even though there is considerable disagreement about this. Economically prosperous countries such as the United States and Japan are well above this level at 125 per cent and more than 250 per cent respectively. Since the beginning of this millennium the Swiss government’s debt ratio had fallen from just over 45 per cent to just over 25 per cent by 2019 (see Chart G 4). Even if it were to rise to 35 per cent or as much as 45 per cent, it would still be well below those of the countries used here for comparison – and still below Switzerland’s highest debt ratio of the last four decades (47 per cent in 1998).

Debt service: Switzerland in a comfortable situation

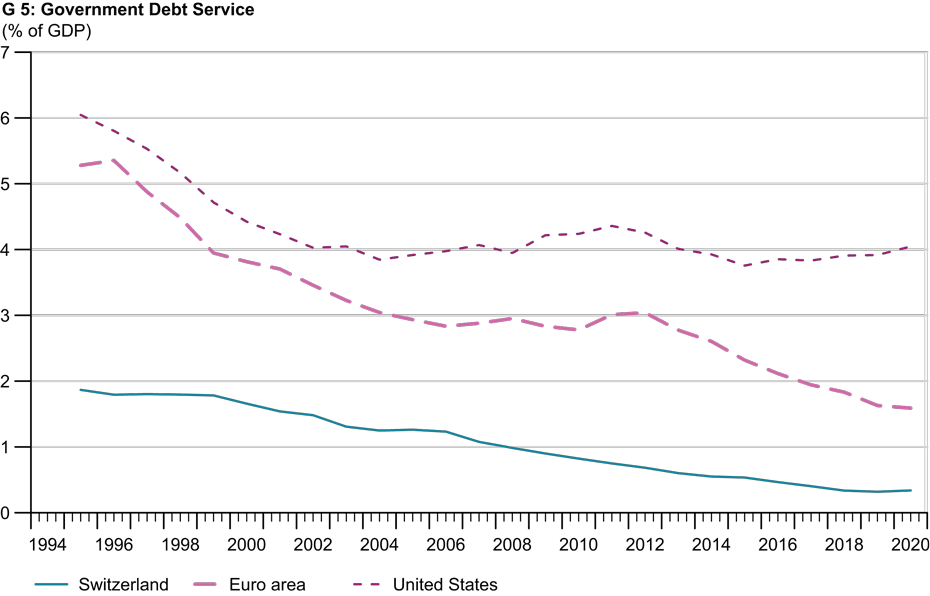

The third and fiscally most important aspect concerns debt servicing. This can become a problem even with relatively low debt ratios if the interest rates on revolving issues of government bonds shoot up, as the euro crisis has painfully shown. Here too, however, Switzerland is in a historically uniquely comfortable position. Debt service as a percentage of GDP has fallen significantly over the past 25 years and is currently less than 0.4 per cent – well below the corresponding shares for the euro area and the United States (see Chart G 5). The credit quality of Swiss government bonds should therefore be beyond doubt for the foreseeable future.

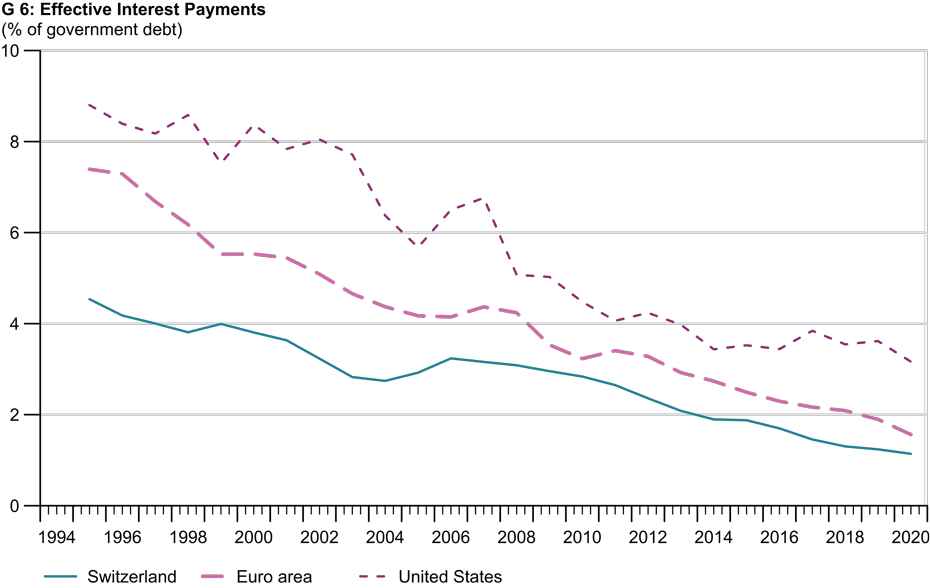

Interest rates on Swiss government bonds are currently negative, and effective interest payments have fallen from 4.5 per cent of outstanding Swiss government debt to only 1.2 per cent over the past 25 years (see Chart G 6). Financial investors are now even prepared to pay a fixed negative long-term interest rate for safe Swiss bonds. Since outstanding government debt is reissued on a revolving basis, the current record low interest rates mean that these effective interest rates for servicing Swiss government debt will continue to fall for some time. And even if today’s interest rates were to rise again (which does not look likely for the foreseeable future), the servicing of government debt would only gradually become more expensive.

Balanced national budget would quickly reduce debt ratio

Consequently, Swiss public finances will remain in good shape in every respect both during and after the current crisis. The rapid debt reduction that has been called for by many is therefore not imperative, especially since a return to a balanced budget over the economic cycle would swiftly reduce the debt ratio.

The arithmetic behind this is simple: the rate of change in a ratio is the difference between the rates of change in the numerator and denominator. The debt brake requires that the budget be balanced over the economic cycle after the crisis, i.e. the rate of change in the level of debt should be zero. The rate of change in the debt ratio over the economic cycle in the long term then corresponds, with the opposite sign, to the growth rate of nominal GDP, i.e. the sum of real economic growth and the inflation rate. Assuming a balanced budget and positive nominal economic growth, the debt ratio would thus converge towards zero by itself.

Given the current outlook, the following is an outline of the scenarios under which the country could return to its pre-crisis government debt ratio. As things stand today, the increase in Switzerland’s debt ratio expected as a result of the pandemic may amount to about 5 pp. We can cautiously assume real economic growth of 1.5 per cent and inflation of 0.5 per cent after the crisis or, more optimistically, real economic growth of 2 per cent and inflation of 1 per cent (the SNB's ‘unofficial’ inflation target). Assuming the scenario with a 5 pp increase in the debt ratio and moderate growth in nominal GDP, the pre-crisis debt ratio would be reached after nine years whereas3, under the scenario with stronger growth, this ratio would be reached after just six years. If the debt ratio were to increase by 10 pp, it would return to its initial level after eleven years in the event of strong economic growth, while it would return to this level after 17 years in the case of moderate economic growth. Should there be any further waves of pandemics in Switzerland that increase the debt ratio by a full 20 pp, it would return to its initial level after 30 years even under the scenario with nominal economic growth of only 2 per cent. Swiss government bonds of this maturity are currently being subscribed at negative interest rates, so the government would earn income even if it kept its nominal debt constant until the debt ratio had fallen back to its pre-crisis level.

-------------------------------------------

1) See external page https://www.efv.admin.ch/efv/de/home/themen/finanzstatistik/daten.html.

2) The data have been taken from the AMECO macroeconomic database. Debt levels are calculated according to the Maastricht criteria. Switzerland’s debt ratios up to 2019 have been obtained from the Federal Finance Administration. A KOF forecast has been used for the period from 2020 to 2022.

3) The calculation is as follows: the rate of change in a fraction is the difference between the rates of change in the numerator and denominator. If the level of debt remains constant, the rate of change in the numerator is zero and the debt ratio then changes, with the opposite sign, in line with the growth rate of nominal GDP. An increase in the debt ratio from 25 pp to 30 pp corresponds to a rise of 20 per cent. Once nominal GDP has increased by 20 per cent, the debt ratio has returned to its initial level. Assuming annual (exponential) growth of 2 per cent, this happens after nine years.

You can find the full version of this post in the blog external page «Ökonomenstimme».

Contact

Dep. Management,Technolog.u.Ökon.

Weinbergstr. 56/58

8092

Zürich

Switzerland