The situation in the labour market remains challenging

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

On paper, employment in Switzerland has hardly fallen despite the coronavirus crisis. But a brief look behind the scenes shows that the pandemic and its economic impact have also affected the labour market. Many companies will remain reluctant to create new jobs on a large scale until the current uncertainty has subsided.

It is quite astonishing: in 2020 the Swiss economy was hit by the worst economic crisis in decades, yet at the end of the year almost the same number of people were employed as a year earlier. Expressed in full-time equivalents, only 0.3 per cent fewer people were employed at the end of 2020 than at the end of 2019. According to the Swiss Labour Force Survey, the number of people in employment in the fourth quarter of 2020 had virtually returned to the level of the previous year. However, a closer look at the labour market data reveals that these figures only show one side of the coin. There are at least three reasons for this.

Firstly, the employment rate – i.e. the proportion of the working-age population that is employed – fell. The reason for this is that Switzerland's population grew in 2020. According to KOF’s latest population scenarios, Switzerland’s permanent resident population increased by 0.7 per cent last year. The working-age population, i.e. individuals aged 15 to 64, is estimated to have risen by 27,000 – an increase of half a per cent. This population growth arises, among other things, from positive international net migration. The latest figures from the State Secretariat for Migration reveal that, despite the COVID-19 crisis, around 55,000 foreigners immigrated to Switzerland in net terms, as in the previous year.

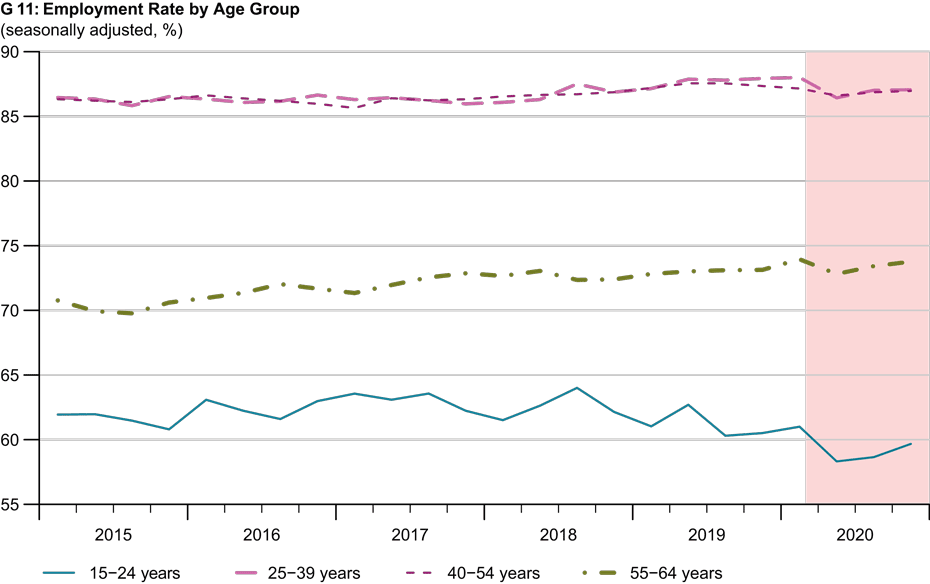

Chart 11 shows the employment rate for four age groups. It reveals that there was a decline in the employment rate especially among the two younger groups of people. For 15-24 year-olds, the employment rate in the fourth quarter of 2020 was a good one percentage point below its pre-crisis level. The chart suggests that the COVID-19 crisis has so far reduced the opportunity for young people in particular to take up gainful employment. According to figures from the Federal Statistical Office, there are currently considerably more young people who would be willing to take up employment in principle but are not actively looking for it. This is probably due, among other things, to the fact that younger workers are more likely to be employed in sectors that have been severely affected by the crisis.

Public sector driving employment growth across the economy as a whole

A second reason why the official figures conceal the labour market effects of the COVID-19 crisis is that employment levels across the economy as a whole were largely driven by the increase in public-sector employment. Most private sectors of the economy, on the other hand, have reduced their workforces – on a massive scale in some cases.

Chart 12 shows how full-time equivalent employment changed in various sectors between the end of 2019 and the end of 2020. The differences between industries are stark. Some service sectors saw considerable job growth despite or even because of the crisis. For example, full-time equivalent employment increased at banks (2 per cent), at insurance companies (1.7 per cent) and in the information and communication sector (2.2 per cent), although almost all of this contribution was made by the IT sector (up 4.5 per cent). However, the public service sectors such as healthcare and social services (3 per cent) and education (2.3 per cent) also grew strongly. Public administration in the narrower sense created over 3,000 new full-time equivalent jobs last year (2 per cent). On the other hand, there were huge job losses of more than 5 per cent in 2020 in the hospitality industry, at manufacturers of electrical equipment and among other business service providers, which include the cleaning and temporary-employment sector as well as travel agencies.

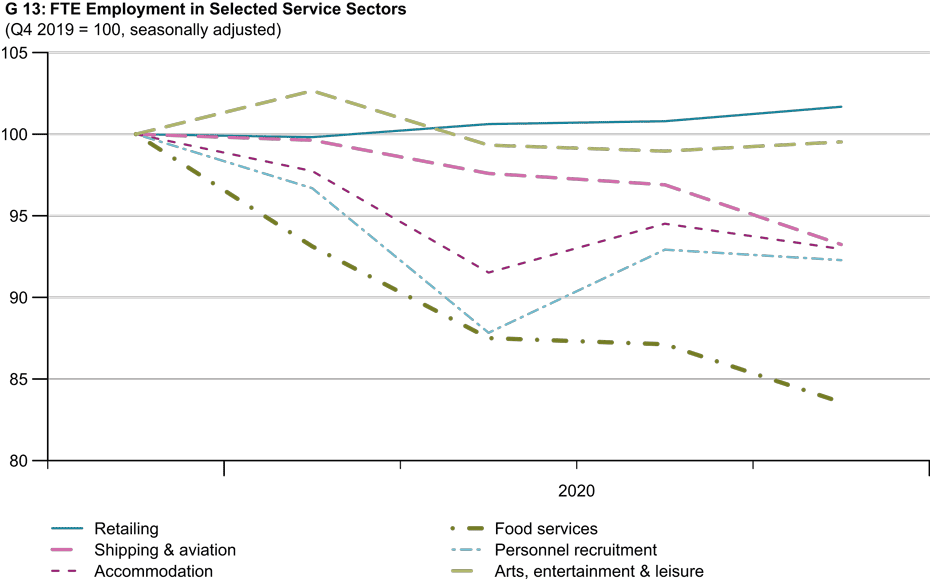

One in six jobs in the food service sector was lost despite heavy use of short-time working

Chart 13 looks more closely at the employment trends in some of the service industries particularly affected by the crisis. The largest decline in employment was in the food service sector. Almost one in six jobs in restaurants, bars and catering companies was lost over the course of last year – even though the sector made heavy use of short-time working. Accommodation, shipping and aviation also fared poorly, with employment down by about 7 per cent. At least the accommodation sector – having suffered a serious slump in the first half of the year – has seen some recovery since the summer. After witnessing a massive decline in employment in the first half of the year, the personnel recruitment sector also saw a slight recovery in the second half of the year. Temporary workers, who are hired as flexible labour in good times to cover peaks in demand, are sometimes the first to be laid off in times of crisis when these peaks in demand disappear.

The retail sector, on the other hand, which was also severely affected by the restrictions, increased its number of jobs in 2020. At the end of 2020 there were around 1.7 per cent more FTE employees than in the previous year. This represents a turnaround in employment trends within the retail sector, where employment had previously been declining for years. However, these figures are likely to conceal significant differences between individual businesses within the sector.

The loss of work during the crisis has been equally as great as the slump in value added

However, the most important reason why the employment figures conceal the extent of the crisis is that the coronavirus pandemic has caused a huge reduction in working hours. This is due to short-time working, which has enabled companies to reduce their volumes of work – and thus wage costs – without having to announce layoffs.

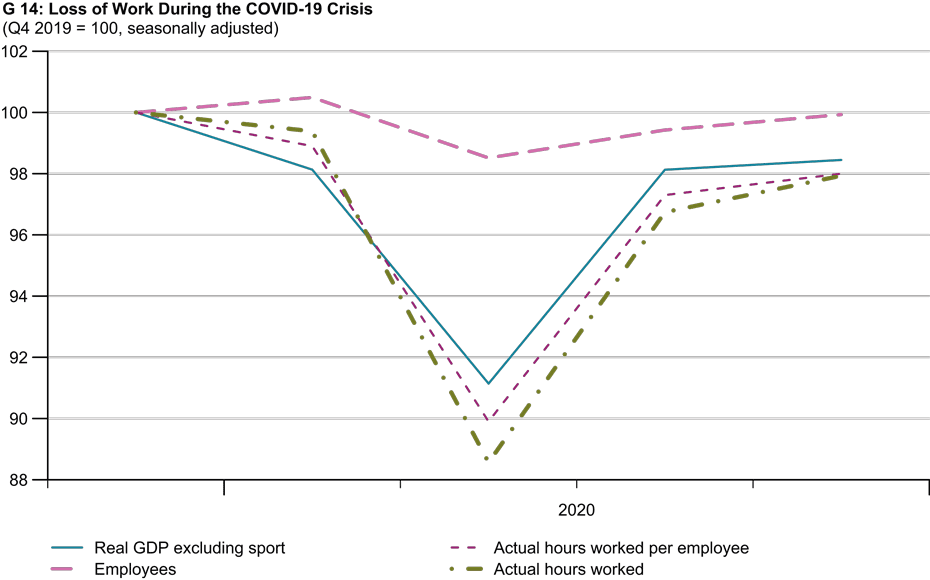

Employees reported as being on short-time working are fully counted in the employment statistics. Consequently, the employment and labour force figures massively understate the loss of work caused by the crisis. This is illustrated by the chart 14. It shows how real GDP, the number of those employed, hours worked per employee and the total volume of work – the total of all hours worked by employees – changed over the course of 2020. The chart uses figures on hours worked per employee published by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). The data is based on the Swiss Labour Force Survey.

The chart shows how dramatically working hours per employee fell in 2020. The decline during the second quarter was around 10 per cent compared with the fourth quarter of 2019. Working hours per employee in the third and fourth quarters remained at least 2 per cent below their pre-crisis levels. The data shows that the decline in hours worked per employee was at least as great as the slump in GDP. Firms whose demand collapsed or whose activity was curtailed transferred their drop in value added to the working hours of their workforce. Since the number of employees (red dashed line) decreased temporarily despite short-time working, the decline in total hours worked – i.e. the hours worked by all employees combined (green line) – was even greater than the slump in GDP (according to the data for the second to fourth quarters of 2020).

This chart has at least two key implications. First, many workers have felt the impact of the crisis by reducing their working hours. And, second, labour productivity – value added per hour worked – may have been higher at the end of the year than at the beginning, as real GDP excluding sport fell by less than total hours worked in the fourth quarter. If we were to measure labour productivity in terms of GDP per employee instead, we would arrive at the opposite result.

Short-time working almost six times as widespread as during the financial crisis

The massive reduction in hours worked per employee during the crisis is a major effect of the widespread use of short-time working. At the peak of the first lockdown in April 2020, 1.34 million employees – or about 28 per cent of all those employed in Switzerland – were on short-time working. By November 2020, 38,300 firms were still reporting almost 330,000 employees as being on short-time working. Companies' use of short-time working rose sharply again at the turn of the year after the restrictions were tightened in December and further plant closures were approved. The pre-announcement data suggests that between 500,000 and 600,000 employees will be reported as being on short-time working in February 2021. This means that about five to six times as many employees were affected by short-time working in February as at the height of the financial crisis in 2009. This shows that the crisis in the labour market is far from over. In fact, according to KOF’s latest economic forecast, seasonally adjusted total employment will fall slightly in the first quarter of 2021.

Catch-up effect in the second half of the year

The performance of the labour market in the coming months will largely depend on whether the vaccination campaign enables the restrictions to be relaxed as planned without the number of cases rising sharply. If this is the case, the labour market can be expected to improve over the coming months owing to the gradual easing of restrictions. Companies are likely to create slightly more jobs again, and those that are currently suffering particularly as a result of the crisis-related measures will cut back on short-time working. Finally, sectors such as food services which are once again able to operate without restrictions could benefit from certain catch-up effects on the part of consumers. KOF therefore expects catch-up effects to begin in the second quarter of this year and then to become visible in the employment statistics, particularly in the second half of 2021. FTE employment and the number of those employed will grow at an above-average rate and will be driven by job growth in sectors that were particularly affected by the restrictions.

Despite this recovery, the situation in the labour market is likely to remain challenging until the end of 2021. Many companies will remain reluctant to create new jobs on a large scale until the uncertainty about the further progress of the pandemic has subsided and their margins have improved. In addition, the number of business closures could increase this year. After all, a large number of employees are on short-time working and in some cases it could turn out that some of these jobs will not be needed after the crisis is over. Moreover, as the experience of the financial crisis suggests, layoffs are likely to occur in the second half of the year because the first companies will have used up the maximum entitlement period for short-time working, which is currently 18 months, and will be forced to cut the jobs affected.

The latest economic forecast for Switzerland can be found in the external page KOF Economic Forecast of the end of March.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland