Do deflation and rigid wages harm the economy? The importance of wage rigidity for monetary policy

- Labour Market

- Monetary Policy

- KOF Bulletin

At the beginning of 2015 the Swiss National Bank abandoned the franc-euro minimum exchange rate, triggering a deflationary shock. How did incomes and unemployment of workers with and without rigid wages react to this?

Many economists consider deflation (i.e. a prolonged decline in general price levels) to be harmful for at least three reasons. First, consumers postpone purchasing decisions in anticipation of lower prices. Second, falling prices make it more difficult to meet nominal loan obligations. And third, businesses cut jobs in response to falling revenues if workers resist nominal wage cuts. Fearing these negative consequences for the economy in particular, most central banks aim to keep inflation well within positive territory.

Inflation has fallen in most OECD countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (by 0.5 percentage points on average). The fear of impending deflation is also reflected in the rapid cuts in key interest rates and the recently launched bond-buying programmes of many central banks.

Deflationary shock after the Swiss franc’s exchange-rate floor against the euro was lifted

However, there is little academic research examining the negative effects of deflation. Moreover, there is no consensus in the existing literature as to whether wage rigidities – i.e. lack of wage flexibility – are relevant (e.g. Basu and House 2016). We therefore investigate whether deflation due to nominal wage rigidities leads to lower incomes and higher unemployment (Funk and Kaufmann 2020). We use a new dataset on the incomes, employment and wages of the Swiss labour force. The data come from the AHV Central Register and the Wage Structure Survey, a company survey conducted by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. The survey data contain information on contractual wages, so we can divide individuals into two groups. The ‘treatment group’ includes individuals with rigid wages, i.e. those subject to a pay freeze in 2014. The ‘control group’ includes individuals with flexible wages, i.e. those subject to a modest pay cut in 2014. We then use the AHV data to analyse the different income and employment patterns in the two groups.

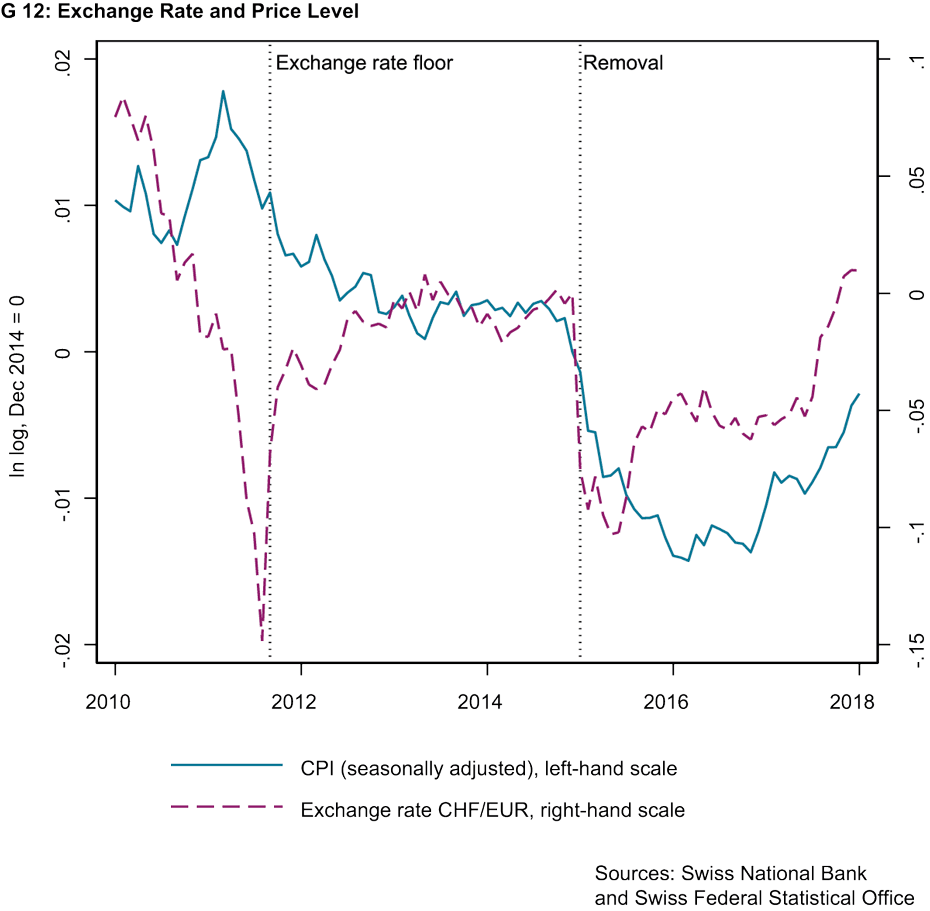

We use a natural experiment to measure the impact of a deflationary shock on the two groups. In January 2015 the Swiss National Bank abandoned the franc’s exchange-rate floor against the euro, which caused the currency to appreciate by 10 per cent and prices to decline by 1 per cent (see G 12). To measure this impact, we compare the different income and unemployment patterns in the two groups before and after the currency appreciation.

Deflation and wage rigidities lead to lower incomes and higher unemployment

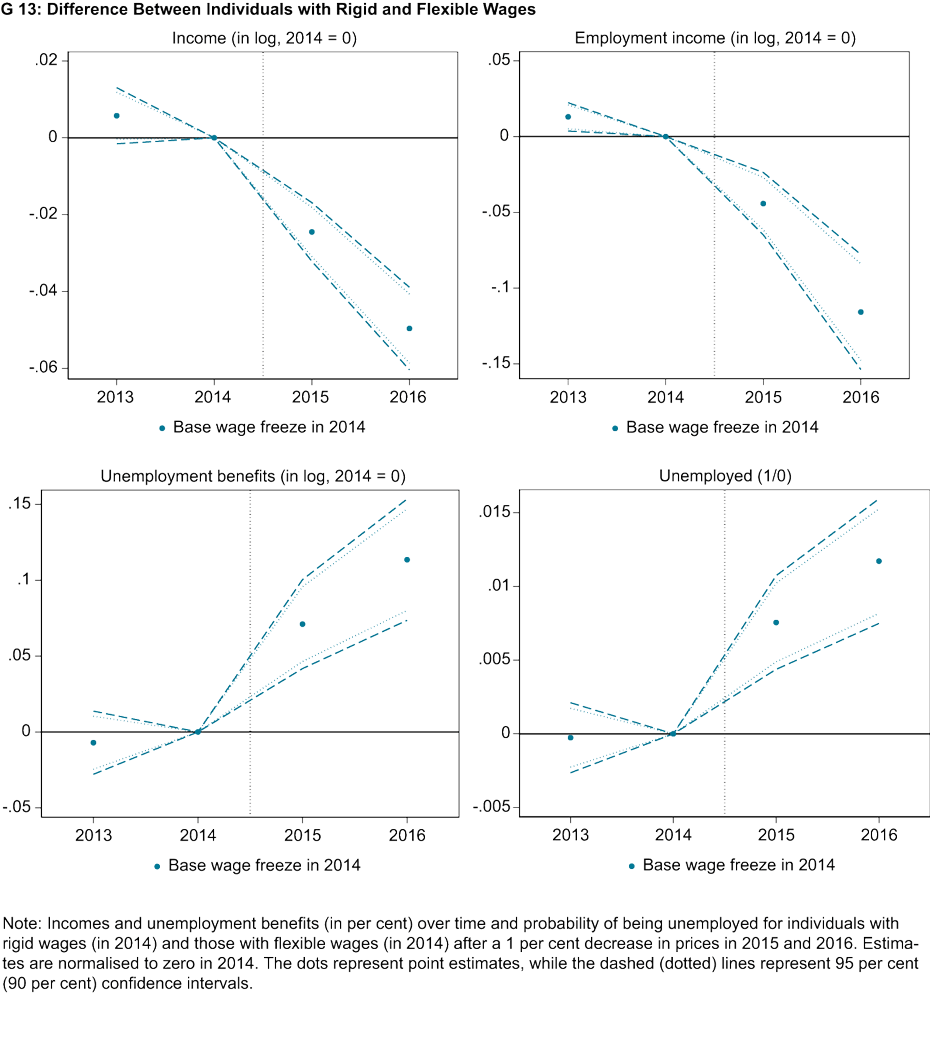

The impact of wage rigidities is considerable (see G 13). The incomes (employment incomes) of individuals with wage rigidities fall by 5 per cent (12 per cent) compared with the control group. The larger drop in employment incomes can be explained by the fact that unemployment benefit replaces part of these incomes if an individual with rigid wages loses their job. In fact, the probability of becoming unemployed is 1.2 percentage points higher for individuals with rigid wages.

For identification purposes we focus on individuals close to the origin of the wage change distribution. However, this means that the results are not representative of the economy as a whole. We therefore estimate representative aggregate effects by using our estimation model to predict income and employment for individuals in the treatment group without wage rigidities. We then use sample weights to aggregate these individual predictions together with the actual observations for individuals without wage rigidities. These effects are also relevant for the economy as a whole. Income and employment income are 0.4 per cent and 1 per cent lower respectively compared with a counterfactual situation without wage rigidities. In addition, the number of unemployed is more than 2 per cent higher.

What do wage rigidities mean for monetary policy?

Our findings have implications for monetary policy and the optimal level of inflation targeting. On the one hand, zero or slightly negative inflation is desirable because it minimises the cost of holding money (Friedman 1969). Moreover, deviations of inflation from zero are costly because of the misallocation of resources owing to relative price distortions (Yun 2005). On the other hand, some researchers argue that the cost of a (moderately) positive inflation rate is relatively low (Nakamura et al. 2018). In addition, positive trend inflation relaxes the effective zero-interest-rate bound (see Andrade et al. 2019) and reduces distortions arising from nominal wage rigidities (Tobin 1972, Kim and Ruge-Murcia 2009). These factors need to be weighed against each other to determine the optimal level of inflation targeting.

By the time the global financial crisis hit, most central bankers had recognised that an effective interest-rate floor clearly constrains monetary policy. The importance of wage rigidities for the optimal level of inflation is more controversial. Issing et al. (2003), for example, argue that "...the importance of nominal rigidities in practice is highly uncertain and the empirical evidence is inconclusive, especially for the euro area" and "...it seems difficult to rule out the possibility that such rigidities would diminish and even disappear in the context of a permanent and fully credible transition to a low inflation environment."

The Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) have thoroughly reviewed their monetary policy strategies in light of the challenges that arose during and after the financial crisis. Our findings provide new insights that are valuable for such strategic reviews. Nominal wage rigidities do not disappear even during a prolonged period of mild deflation. Moreover, nominal wage rigidities have negative effects on income and employment after an exogenous deflationary shock. Central banks and academics should therefore take nominal wage rigidities into account in their choice of monetary policy strategies, especially with respect to the type and level of nominal targets.

References

Andrade, P., J. Galí, H. L., Bihan, and J. Matheron (2019): The optimal inflation target and the natural rate of interest. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 3, 173-230, external page online.

Basu, S. and C. L. House (2016): Allocative and remitted wages: New facts and challenges for Keynesian models. In Taylor, J. B. and H. Uhlig, editors: Handbook of Macroeconomics. vol. 2, 297-354, Elsevier, external page online.

Funk, A. K. and D. Kaufmann (2020): Do sticky wages matter? New evidence from matched firm-survey and register data. IRENE Working Papers 20-06, IRENE Institute of Economic Research, University of Neuchâtel.

Friedman, M. (1969): The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago: Aldine.

Issing, O., I. Angeloni, V. Gaspar, H.-J. Klöckers, K. Masuch, S. Nicoletti-Altimari, M. Rostagno, and F. Smets (2003): Background studies for the ECB’s evaluation of its monetary policy strategy. European Central Bank, external page online.

Kaufmann, D. (2020): Is deflation costly after all? The perils of erroneous historical classifications. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 35, 614-628, external page online.

Kim, J. and F. J. Ruge-Murcia (2009): How much inflation is necessary to grease the wheels? Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(3), 365-377, external page online.

Nakamura, E., J. Steinsson, P. Sun, and D. Villar (2018): The elusive costs of inflation: Price dispersion during the U.S. Great Inflation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1933-1980, external page online.

Tobin, J. (1972): Inflation and unemployment. American Economic Review, 62(1), 1-18.

Yun, T. (2005): Optimal monetary policy with relative price distortions. The American Economic Review, 95(1), 89-109, external page online.

Contact

No database information available