Have financial markets decoupled from the real economy?

- Monetary Policy

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

Reality for much of the year so far during the coronavirus crisis has consisted of lockdowns, working from home and living a dreary everyday existence while stock markets have kept hitting new highs. However, there are academic explanations for this apparent contradiction.

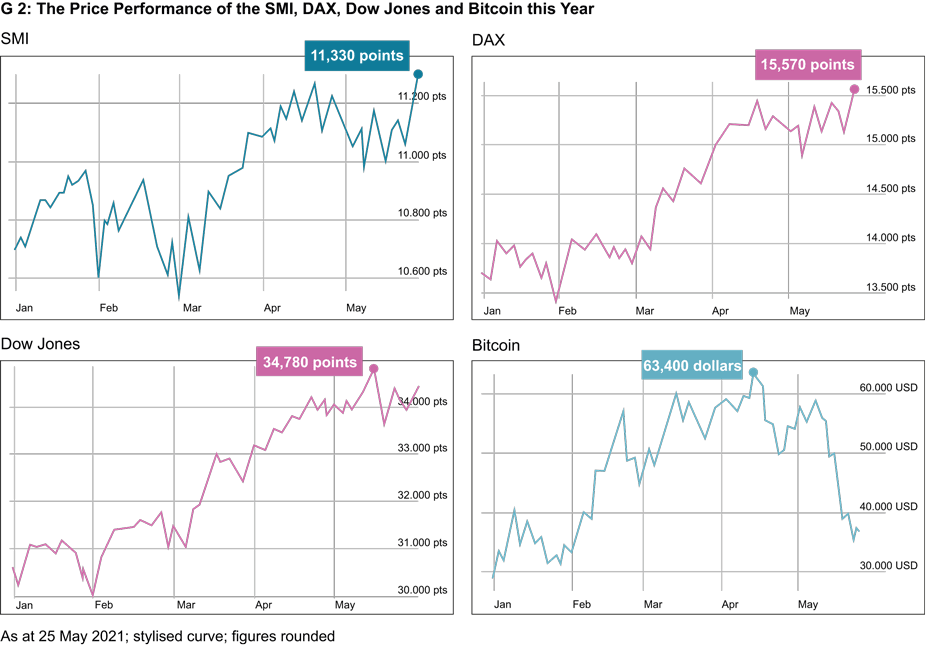

Prices on financial markets – whether technology shares, classic industrial stocks, cryptocurrencies, timber, wheat or copper – have risen sharply in 2021. Many share indices such as the SMI, the Dow Jones and Germany’s DAX share index have even reached all-time highs recently. Bitcoin also rose to record highs initially but has since fallen back again (see G 2).

At the same time, economic activity in almost all countries of the world continues to be constrained by the coronavirus restrictions. The tourism and hospitality sectors in many countries have remained idle for long periods this year owing to the forced closure of hotels and restaurants. The retail sector has also largely remained closed throughout much of Europe in 2021, leaving many consumers with little opportunity to spend their money except for online. This forced saving has caused more and more investors to turn to the stock market, and share prices have continued to rise since their coronavirus-induced low in March 2020.

Are we currently witnessing a bubble in financial markets?

So have financial markets decoupled from the real economy during the coronavirus crisis? Or, to put it another way, are we currently witnessing a bubble in financial markets? Heiner Mikosch, Head of KOF’s International Business Cycle Section, believes there is no clear answer to this question. "A bubble is not something we can see in reality or whose existence or non-existence we can investigate in the same way as the question of whether or not the object over there in the field is a horse. Bubbles are mental constructs."

It is difficult to define the term 'bubble'. "To define a bubble as a deviation from a fundamental value, I need a robust model that can calculate the fundamental value. This model in turn depends on fundamental assumptions about market participants. However, there is no consensus on these assumptions in economics. In retrospect – even years or decades later – it is therefore not possible to say with absolute certainty and definitively whether or not we have witnessed a bubble during a particular period," says Mikosch.

The concept of bubbles is controversial in economics

There are even economists who advocate a theory of rational markets and therefore believe that bubbles simply do not occur, although Mikosch does not hold this view. "Personally I think that bubbles do exist, or – to put it a little more philosophically – that there are always market phenomena that we can meaningfully call bubbles," says the graduate of economics, philosophy and political science. It is possible to adapt one’s model to reality so as to show that there has never been any such bubble. But whether the model then still makes sense is another question.

Are the current valuations in financial markets excessive?

Mikosch can – at least partially – understand the current highs on stock markets. "Market participants apparently do not believe that the coronavirus crisis will have a substantial long-term impact on economic performance. This view is also largely consistent with our research. Consequently, this will result in a discount on a (fictitious) scenario without any coronavirus pandemic, but these discounts are not very large," says the KOF economist. And investors are basically future-orientated. A company’s share price is – roughly speaking – derived from the firm’s discounted future profits, explains Mikosch, who has been researching macroeconomics at KOF since 2007.

However, Mikosch also finds that potential risks are currently being ignored by many market participants. During the coronavirus pandemic, for example, there was considerable uncertainty about future developments for some time, yet stock markets rebounded fairly quickly. "Even now, forecasts by almost all economic research institutes indicate that there are still clear uncertainty factors such as new variants. Although such uncertainties are normally priced into financial markets, this appears to be happening to a lesser extent than usual at the moment."

How central banks are driving up share prices

This trend, in turn, is essentially related to the monetary policies being pursued by central banks. "Market participants are apparently assuming that central banks want to prevent a downturn at all costs," says Mikosch. This is also the view of his colleague Anne Kathrin Funk, who has been researching monetary policy at KOF since 2015. "The sharp rise in share prices this year doesn’t really surprise me because there is simply an incredible amount of liquidity in the market. Central banks have been pursuing extremely expansionary monetary policies, and interest rates have been low throughout a very long cycle. The money is available now and this capital has to go somewhere. That makes for rising share prices," she says.

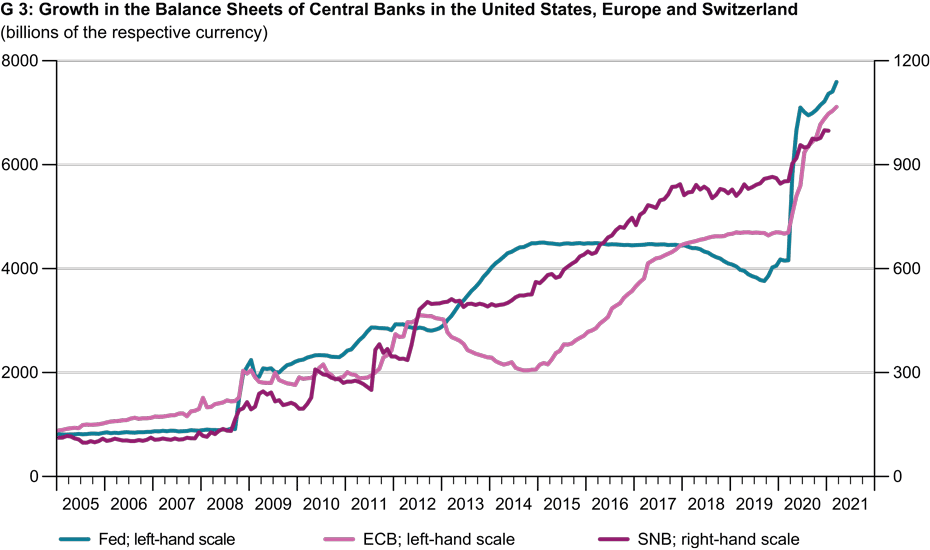

KOF Director Jan-Egbert Sturm also believes that the current stock market valuations are understandable. He emphasises the role played by central banks in the general rise in share prices across almost all sectors. “The movements in financial markets can be explained relatively well. Firstly, economic prospects have improved and, secondly, central banks have turned on the taps more than ever before during the coronavirus crisis, so there is a lot of liquidity in the market,” says Sturm. As chart G 3 shows, central banks in Europe, the United States and Switzerland have disproportionately increased the size of their balance sheets – which had already expanded after the financial crisis – during the coronavirus pandemic.

However, Sturm considers the surge in commodity prices to be partly a short-term phenomenon. "There have been logistical problems and production shortages on the way out of the lockdown, which has limited the availability of raw materials and thus increased prices," adds Sturm. This effect is at least partly temporary, so it is premature to talk of a new super cycle in commodities. Rather, it is merely a case of things returning to normal, as can be seen with the oil price.

Cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile

Sturm considers the hype around bitcoin, which recently rose to over 60,000 dollars, to be excessive. "For me, bitcoin is a financial product but not yet a means of payment. I can’t go shopping with bitcoin, just as I can’t go shopping with a share or bond, so I must first convert the bitcoin into a common currency," explains Sturm. Furthermore, the professor of applied macroeconomics is critical of the instability of cryptocurrencies. Their volatility means that no one can calculate in their heads what these currencies are worth, which we do as a matter of course with Swiss francs and euros.

How dangerous is the current expansionary monetary policy?

However, the idea of financial markets decoupling from the real economy is not completely absurd, stresses Funk. Financial markets are now less and less driven by news from the real economy, she explains. "For example, even when bad labour market data are announced, there are sometimes hardly any downturns in share prices." The economist considers the current monetary policy to be “correct and necessary” but also points out the risks. "If our exit from an expansionary monetary policy is accompanied by a stock market crash that triggers a banking crisis so that lending to firms and households grinds to a halt, the contagion can spread to the real economy and cause an economic downturn."

However, there would not necessarily be such a crash if central banks like the ECB scaled back their bond-buying programmes. "Technically, exiting an expansionary monetary policy is not a problem. Central banks simply have to shrink their balance sheets or raise interest rates. The Federal Reserve – the US central bank – has shown how this can be done," says Funk.

In addition to a potential stock market crash, she sees a further risk in rising government debt worldwide. "Very high government debt can also become a fiscal problem at some point. The example of Greece has shown that," says Funk. There are good reasons, she adds, why the EU has restricted government debt by imposing the Maastricht criteria.

Strong risk appetite; corrections to be expected

Like Mikosch, Funk is of the opinion that some investors are currently ignoring risk. "It is not the case that people are simply investing recklessly. However, investors’ risk appetite is relatively strong. In private equity especially there seems to me to be some excessive risk-taking because debt ratios are as high as they were before the financial crisis."

This is another reason why she expects to see corrections in financial markets. It is striking that the bull market in equities has lasted for such a long cycle. However, it is difficult to predict when the correction will come and how strong it will be. "At some point the bull market will be over but, at the moment, many investors are still looking to profit from this market," says the KOF economist.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

No database information available

Director of KOF Swiss Economic Institute

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland