China: a competitor to the EU, a partner to Switzerland?

KOF Bulletin

China’s growing economic and political influence around the world and the impact that this has on Switzerland were the topics of the KOF Economic Forum held on 11 June this year. In Switzerland's China strategy, China is primarily portrayed as a partner whereas, in the EU and the US, China is mainly perceived as a competitor or rival. How does China respond to the West’s approach? And what does this mean for the Swiss economy?

Although Switzerland has maintained diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China since 1950, it has only had a China strategy since March 2021. This is intended to improve the coherence of Switzerland’s relations with the People's Republic and to signal that Switzerland will pursue an independent China policy that continues to be based on partnership. Switzerland will uphold its values by cooperating with like-minded states in the EU and advocate an appropriate place for China within the rules-based multilateral system. In terms of economic policy, the Swiss government would like to see relations develop further. In particular, it is seeking to update the free trade agreement that has been in place since 2014. Cooperation in the financial sector, on tourism and through Swiss companies’ participation in the sustainable development of infrastructure in China and within the framework of the New Silk Road Initiative (BRI) are mentioned as economic policy priorities. The focus on infrastructure is related to the BRI Memorandum of Understanding of April 2019 concerning cooperation in third countries within the framework of the New Silk Road (KOF Economic Forum, June 2019), which has so far been ineffective for the Swiss economy. At the KOF Economic Forum entitled ‘China in Europe: how to strike a balance between partnership and rivalry?’, however, speaker Markus Herrmann, Director Switzerland at consulting firm Sinolytics, expected hardly any opportunities to arise for small and medium-sized Swiss firms in the infrastructure sector.

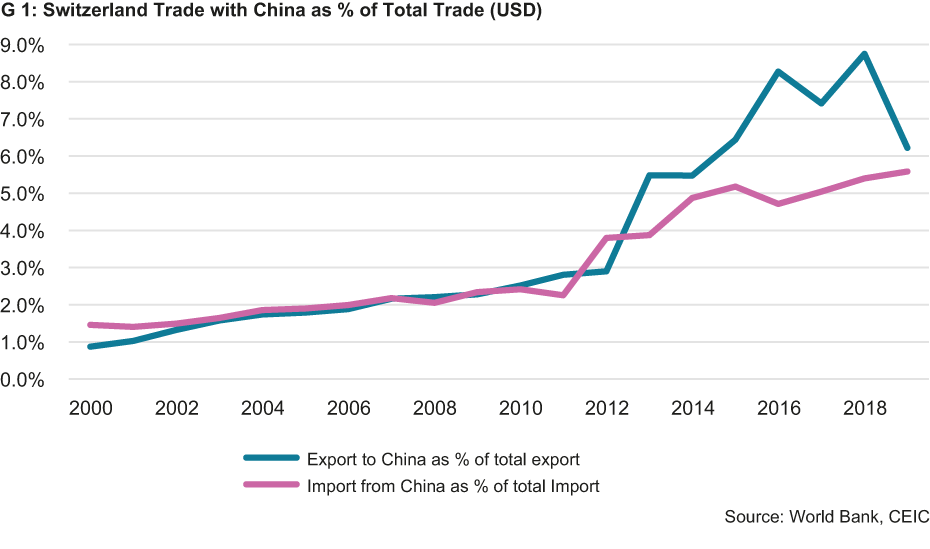

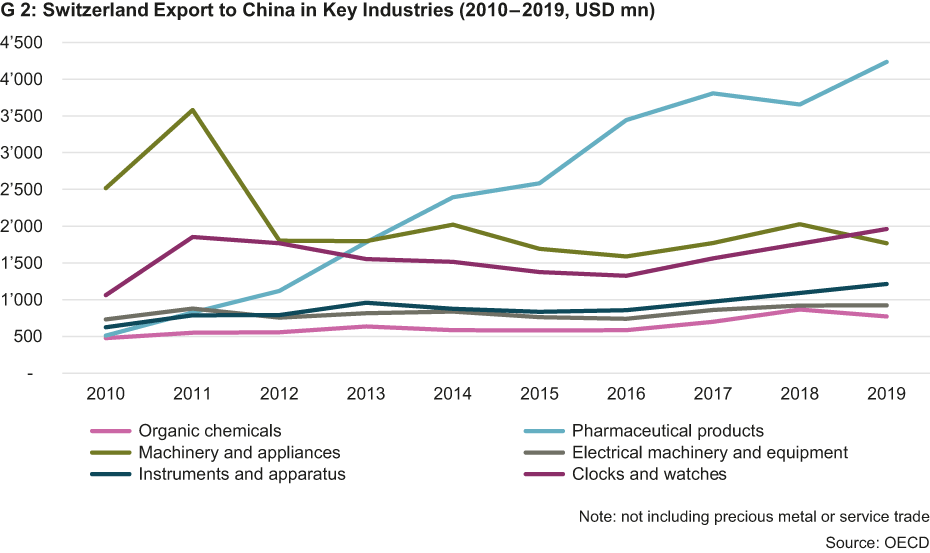

On the whole, economic relations between Switzerland and China have progressed very well in recent years. In 2018, more than five per cent of imports came from China, while six per cent of Swiss exports went to China (see G 1). Switzerland exports mainly pharmaceutical products to China (see G 2). The proportion of bilateral direct and portfolio investment (as a percentage of gross domestic product) has also increased over time. China is now Switzerland’s third most important trading partner, although at 5.7 per cent it is still a long way behind the European Union and the United States and only just ahead of the United Kingdom at 5.5 per cent (figures for 2020, FCA).

Imbalance in China-EU trade with increasingly similar value-added share of exports

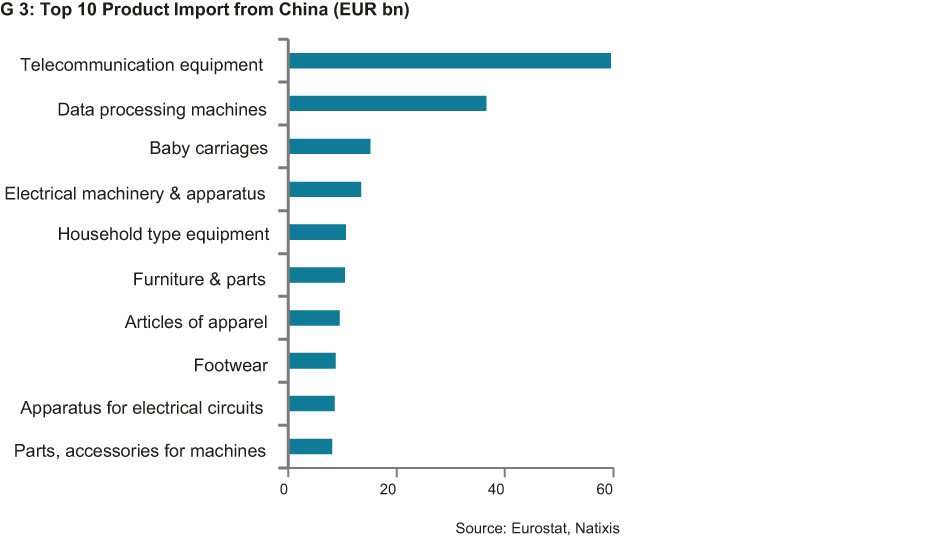

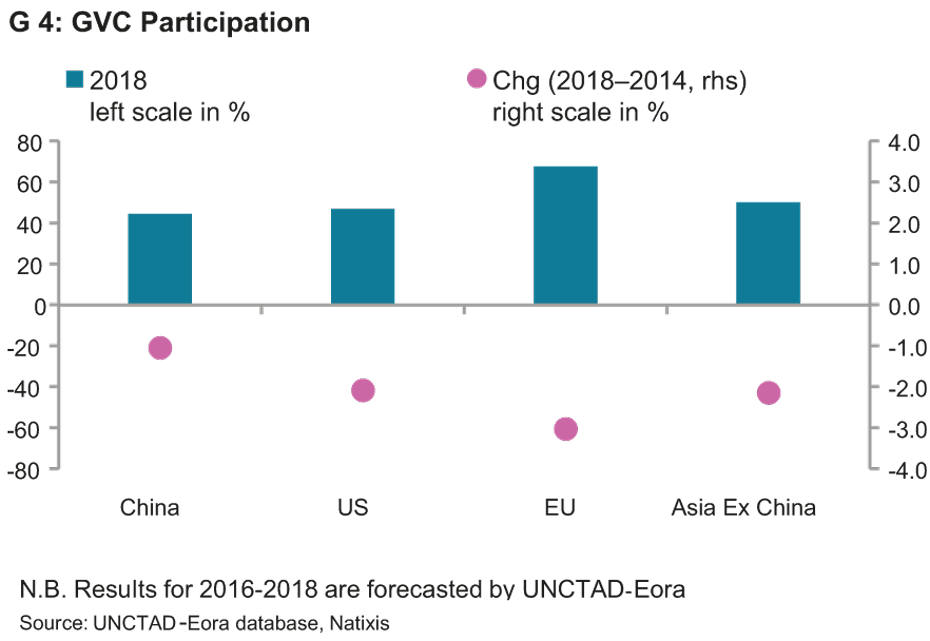

China is also a major trading partner to the member states of the European Union, accounting for 15 per cent of total foreign trade, although there is a large trade deficit, which is unusual for Europe. In addition, Alicia García-Herrero from investment consultancy Natixis emphasised that China’s share of trade with Europe should not be overestimated. The interest in China is mainly explained by the growth expected for the highly dynamic Chinese market. The value added by Chinese exports has increased rapidly in recent years. In 2018, telecommunications equipment and computers were Europe’s two most important imports from China (see G 3), while the EU exported mainly high-tech goods and motor vehicles. Although the value added by European exports to China is still greater than that of European imports from China, this gap is narrowing rapidly (see G 4). The EU is also still the leader at integrating into global value chains, with Europe’s share shrinking faster than the global downward trend in value chains. Alicia Garcia-Herrero explains this by pointing to the trend towards vertical integration – especially in China – and, to some extent also, the reorganisation of value chains. She stresses that the proliferation of state-owned enterprises and subsidies has distorted intra-Chinese competition, which affects the cost of exported products.

Unlike trade in goods, trade in services between the EU and China has stagnated at a very low level and is actually only half the size of Swiss trade in services with the EU. Europe’s exports have so far mainly consisted of tourism and education services, which can primarily be explained by China’s lack of openness in the area of services.

Chinese investment in European high tech and the investment agreement put on hold

The relationship between China and the EU is much more balanced in terms of bilateral investment than it is in trade. Despite the global downward trend in Chinese investment, the EU remains an important investment destination for Chinese firms. Compared with the United States, such transactions involve significantly more Chinese state-owned enterprises in proportional terms. China is increasingly investing in European strategic high-tech companies and the semiconductor sector. Although more than 60 per cent of the EU’s global investment is in the services sector, European investment in China is mainly in manufacturing – especially in those motor vehicles of which there is now an oversupply in China. This is worrying, notes Alicia Garcia-Herrero. Agreements could, in principle, help here and their ratification would send a partnership signal from the EU to China. However, the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between the EU and China is overrated because market access to many sectors in China is still either limited or non-existent, and the agreement would not guarantee better investment protection than existing bilateral agreements. Moreover, it is highly uncertain whether the CAI will ever enter into force as ratification by the European Parliament was put on hold on 20 May 2021. As the economic benefits of the CAI are considered to be modest, the finalised agreement could fail because the political mood has changed since negotiations began.

Differences in American and European perceptions of China’s rise

Geopolitical positioning vis-à-vis China has been high on the political agenda since Joe Biden took office, as the agendas of the G7 summit and the NATO meeting held in mid-June have shown. The United States under President Biden is pushing for other countries to position themselves more clearly on the side of the US. Mikko Huotari, Director of the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), a think tank in Berlin, points out that, in the United States, China is seen primarily as a rival by both Republicans and the governing Democrats and only then as a competitor and only in exceptional cases as a partner. The EU, on the other hand, sees China primarily as a competitor, and the quality of economic relations is paramount. The EU is particularly concerned that the competition rules of the internal market be respected and that European companies, in return for European market access, receive adequate access to the Chinese market. The differences between the US and Europe can be explained not least by a world power’s fear of loss. Moreover, with the exception of the United Kingdom and France, European interests in the Asian region have traditionally been relatively modest. Although some convergence of American and European China policies is likely under President Biden, differences will remain. There is already an intensive dialogue in the area of economic security – on investment controls, for example. Mikko Huotari also expects the transatlantic dialogue on digitalisation, digitalisation infrastructure and cyber security to intensify.

China’s development and government insecurity will determine the country’s foreign relations

Ultimately, it will depend on China how EU-China and Sino-Swiss relations develop. The Chinese leadership is preparing for the upcoming major domestic and foreign policy challenges with the fourteenth five-year plan, which is sometimes also viewed as a de-globalisation plan. The domestic market is to be strengthened over the next five years, which will lead to a de-prioritisation of economic openness but not a fundamental turning away from the world. The goal, according to Mikko Huotari, is to onshore innovation and value chains, and international cooperation will probably continue to be sought, especially in the area of research and development. He sees the insecurity of the Chinese leadership as the reason for the frantic political posturing and the need for more political control, which could lead to unpleasant situations politically and economically. China will increasingly exert influence extraterritorially – as expressed, for example, by the new anti-sanctions law. This anti-sanctions law is regarded by the panellists as a political warning signal. China is strengthening its defence mechanisms and raising them to the level of the established powers. The openly worded text of the law will provide the legal basis for the practice already applied to Australia and would allow any individual or company to be legally prosecuted for implementing sanctions against China. The law will exacerbate conflicts of loyalty for companies and could have a major impact on the business activities of individual firms. At the same time, the Chinese business climate will change as a result of the onshoring strategy of the five-year plan.

The panellists did not want to commit themselves on the future development of supply chain integration with China. The uncertainties here are too great owing to the geopolitical tensions between China and the United States in particular, and the debate around the resilience of supply chains sparked by COVID-19, among other things, is too recent. Given these challenges and China’s new anti-sanctions law, it is important for countries and companies alike to review their strategic dependence on Chinese imports and intermediate products. Based on his brief analysis of the main Chinese imports into Switzerland, Markus Herrmann concludes that there is no obvious strategic import dependency in the case of Switzerland, although more in-depth analysis – such as that conducted by the EU – would be useful.

An Asia-Pacific strategy debate in Switzerland and knowledge of supply chain risks are needed

Given the challenges and changes expected in the Chinese market, German business associations are already discussing how to diversify their target markets and value chains in the Indo-Pacific region. Markus Herrmann expects to see demands for an Asia-Pacific strategy in Switzerland soon as well and calls for more analysis and debate on the impact that regional integration in Asia will have on Swiss exports. In a recent survey conducted by Sinolytics on behalf of Swissmem, Switzerland’s umbrella organisation for the mechanical and electrical engineering industries, half of the 110 companies surveyed said that while the business environment in China has improved for their firms, just as many see the protection of intellectual property rights as one of the major challenges.

China’s rapid and successful integration into the rules-based multilateral system, global competition with a level playing field, legal certainty and market access in China would all be ideal for the Swiss economy. As geopolitical uncertainties are likely to persist for some time, the domestic political framework for the economy needs to be constantly improved and relations with traditional and new markets strengthened. Alicia Garcia-Herrero argues in favour of strengthening the European internal market by dismantling numerous existing internal market barriers instead of following the example of the large Chinese and American investment programmes. According to Markus Herrmann, Switzerland also needs an internal reform programme. As far as Sino-Swiss relations are concerned, he expects Switzerland to maintain a partnership-based and, above all, competition-driven relationship with China and to adopt rival positions only in selected individual cases. From Switzerland’s perspective the shift in the geopolitical balance of power must be manoeuvred prudently and largely independently and strategic import dependencies on China must be avoided. However, Swiss companies should be aware of the risks in their supply chains and hedge them so that they are prepared for highly challenging scenarios.

Contact