COVID-19 in Switzerland: have the containment measures worked?

KOF Bulletin

In the fight against the pandemic, countries are relying on non-pharmaceutical containment measures. In Switzerland, these have led to a decline in new infections. In addition, the population is helping by making voluntary adjustments to their behaviour.

The KOF Stringency Index documents the stringency of cantonal and national measures

The number of registered COVID-19 cases worldwide exceeded the 200 million mark in August 2021. In addition to vaccination campaigns, non-pharmaceutical measures are an important component in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. The Oxford Stringency Index provides an overview of the measures in place in more than 180 countries. Stringency is measured on a scale from 0 to 100, with a score of 0 indicating no restrictions and 100 indicating the most stringent measures in all categories of the index.

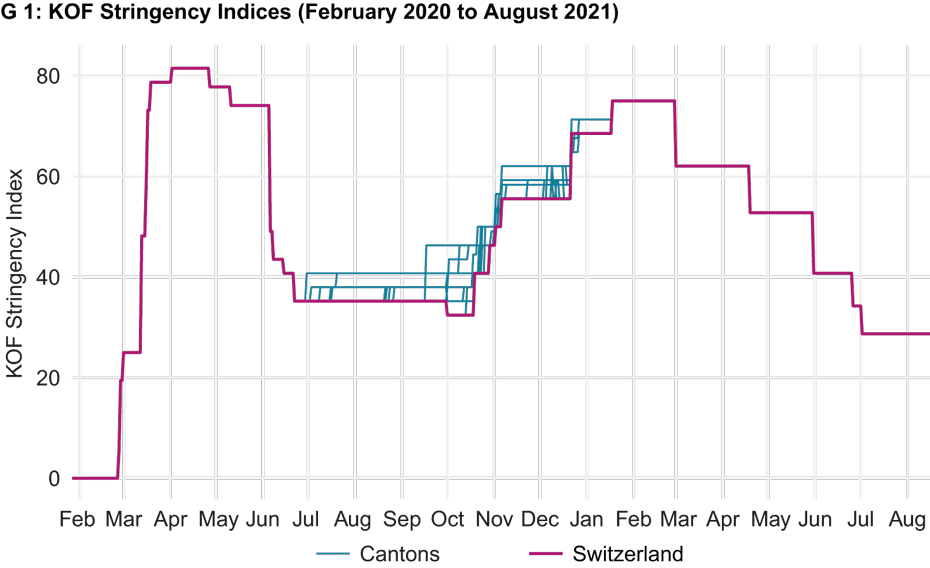

In the specific case of Switzerland, the Oxford Stringency Index is only available for the country as a whole. The considerable political autonomy of the cantons means that containment measures can differ from canton to canton. The cantons made use of this freedom in the autumn of 2020 in particular. KOF has therefore constructed a Stringency (-Plus) Index, which maps the stringency of these measures at both federal and cantonal level. The index comprises ten sub-indicators: the closure of schools and workplaces, bans on events and gatherings, restrictions on public transport, curfews, domestic travel restrictions, international travel restrictions, public information campaigns, and guidelines on the use of mouth and nose protection.

All COVID-19 measures introduced during the lockdown from 16 March to 19 June 2020 were taken by the Swiss government (chart G 1). The following summer was characterised by relatively low case numbers. As the nationwide lockdown restrictions were gradually eased, the cantons were able to impose their own restrictions. October 2020 saw a further rapid rise in new infections, in response to which the cantonal governments increasingly introduced more restrictive regulations. These measures were generally more stringent in the cantons of western Switzerland in autumn 2020. The pioneers of this approach were Geneva, Jura, Neuchâtel and Vaud. The main focus here was on stricter rules in the cultural and catering sectors as well as tighter assembly restrictions. The Swiss government has effectively been imposing these measures again since mid-January 2021, and so the cantonal indices are running at the same level.

What impact do these restrictions have on the rates of infection?

The divergence between cantons in the implementation of measures provides an interesting environment for studying the interactions between restrictions, the rates of infection and the behaviour of the Swiss population. Ideally, the introduction of restrictions leads to behavioural adjustments, which in turn contribute to a slowdown in the rates of infection. For example, closures in the retail sector and restrictions on events are intended to reduce the number of contacts and, thus, potential virus transmission. On the other hand, politicians want to prevent the health system from being overburdened and are reacting to an increase in the number of infections by introducing restrictions. Fear of infection is also leading to voluntary behavioural changes in certain sections of the population.

The interaction of these three factors (restrictions, behaviour and infection rates) was analysed for the period from the end of September to mid-April, which covers the second wave of infections in Switzerland. In this context, the rate of infection was represented by the effective reproduction rate, while the containment measures were represented by the KOF Stringency-Plus indicators.1 The behaviour of the Swiss population was documented in the form of debit card transactions and mobility data. For example, fewer payments are made by debit card while restaurants and shops remain closed. At the same time, mobility is also reduced because trips to restaurants and shopping centres are no longer necessary. Consequently, changes in mobility and in card payment volumes document both voluntary and imposed changes in society’s behaviour.

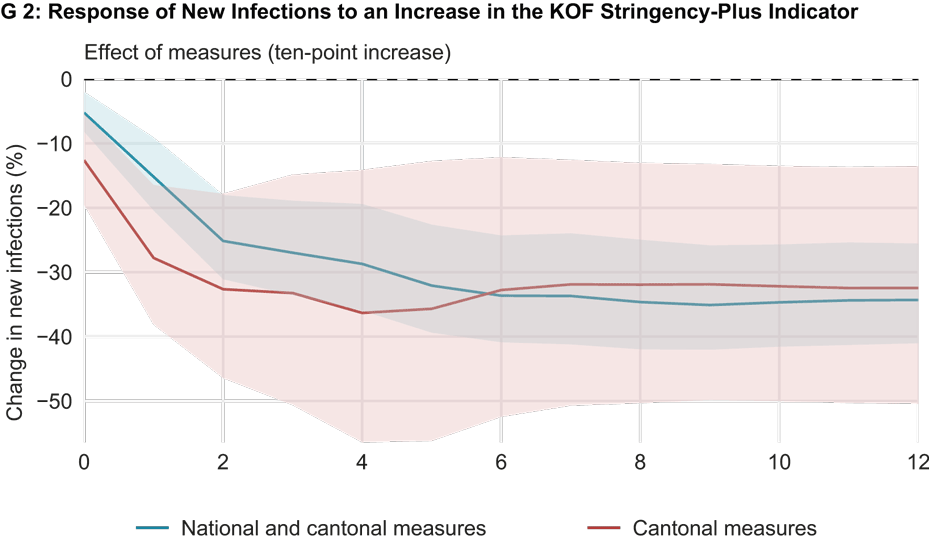

This analysis reveals that stricter measures lead to a reduction in card transactions and mobility and, ultimately, in new infections. Moreover, the effectiveness of these measures does not seem to depend on whether they are adopted at national or cantonal level. Chart G 2 shows in the case of two different models how new infections react to a ten-point increase in the KOF Stringency-Plus indicator over the following twelve weeks. The first model (blue) factors in the variation in all – i.e. national and cantonal – measures to analyse the effect of this stimulus. The second model (red) focuses on the variation in cantonal measures. In both cases, a ten-point increase in the indicator leads to an average reduction of around 30 per cent in new infections after two weeks. This is true of both national and cantonal measures. Since the first model takes account of both temporal and inter-cantonal variations, the effects are estimated with greater certainty and thus more precisely. The second model has the advantage that we consider cross-cantonal pandemic trends separately and, consequently, can better capture the direct impact of (cantonal) measures on the evolution of the pandemic. The difference between the blue and red lines is not statistically significant, which corroborates our assessment that the relationship found is causal.

How does the Swiss population react to an increase in new infections?

Any increase in the number of new infections, on the other hand, results in stricter measures and a decline in consumption and mobility. The response from policymakers is slower than that of the general population, which in turn suggests that at least short-term behavioural adjustments often occur voluntarily. This finding is corroborated if the direct impact of the measures on behaviour is eliminated from the model ex post: short-term changes in behaviour in response to an acceleration of the infection process are voluntary, while about half of the adjustments are triggered by stricter measures after a few weeks.

Which measures are particularly effective?

Any analysis of the effectiveness of individual measures is challenging. Many restrictions are introduced simultaneously, which means that the resulting effects cannot be distinguished from one another. Moreover, some containment measures hardly vary at all over time or show no differences between cantons, which makes statistical identification considerably more difficult. However, the findings for restrictions on gatherings and workplaces suggest that they are more effective than many other measures. These include restrictions on the numbers of people at private meetings, the requirement or recommendation to work from home, and the closure of restaurants and retail outlets.

--------------------------------------------

1) Summer 2020 does not form part of this analysis for two reasons. First, the low number of infections during this period is associated with considerable uncertainty in estimating the effective reproductive number. And second, such low infection rates are likely to suppress behavioural and policy responses to changes in infection growth. In contrast, the 14-day average infection rate during the remainder of the analysis period was usually well above the critical level of 60, raising public and political awareness of the epidemiological situation.

Contacts

No database information available