When national wealth grows faster than national income: a warning sign for the Swiss real-estate market?

KOF Bulletin

In this paper we show that the development of wealth as a percentage of income in Switzerland has followed a J-shaped pattern over the last 120 years: a very stable trend in the 20th century followed by a sharp increase since 2010.

The ratio of an economy’s wealth to its annual income is a useful measure of the importance of the capital stock or the national wealth of an economy. The interpretation of this ratio – which, for the sake of simplicity, we will refer to as β – is plausible. A β of 600 per cent means that we as an economy would have to save our entire income for six years and forego all consumption in order to save the existing capital stock of the economy. Any examination of the wealth-income ratio poses fundamental macroeconomic questions. What is the structure of a country’s wealth? How is national wealth divided into private and state wealth? How does aggregate wealth evolve over time and what role do savings and capital gains play in this process? In a recent Working Paper we combine various historical wealth and income series to estimate β for Switzerland and answer the above questions.

The development of private wealth in the 20th century

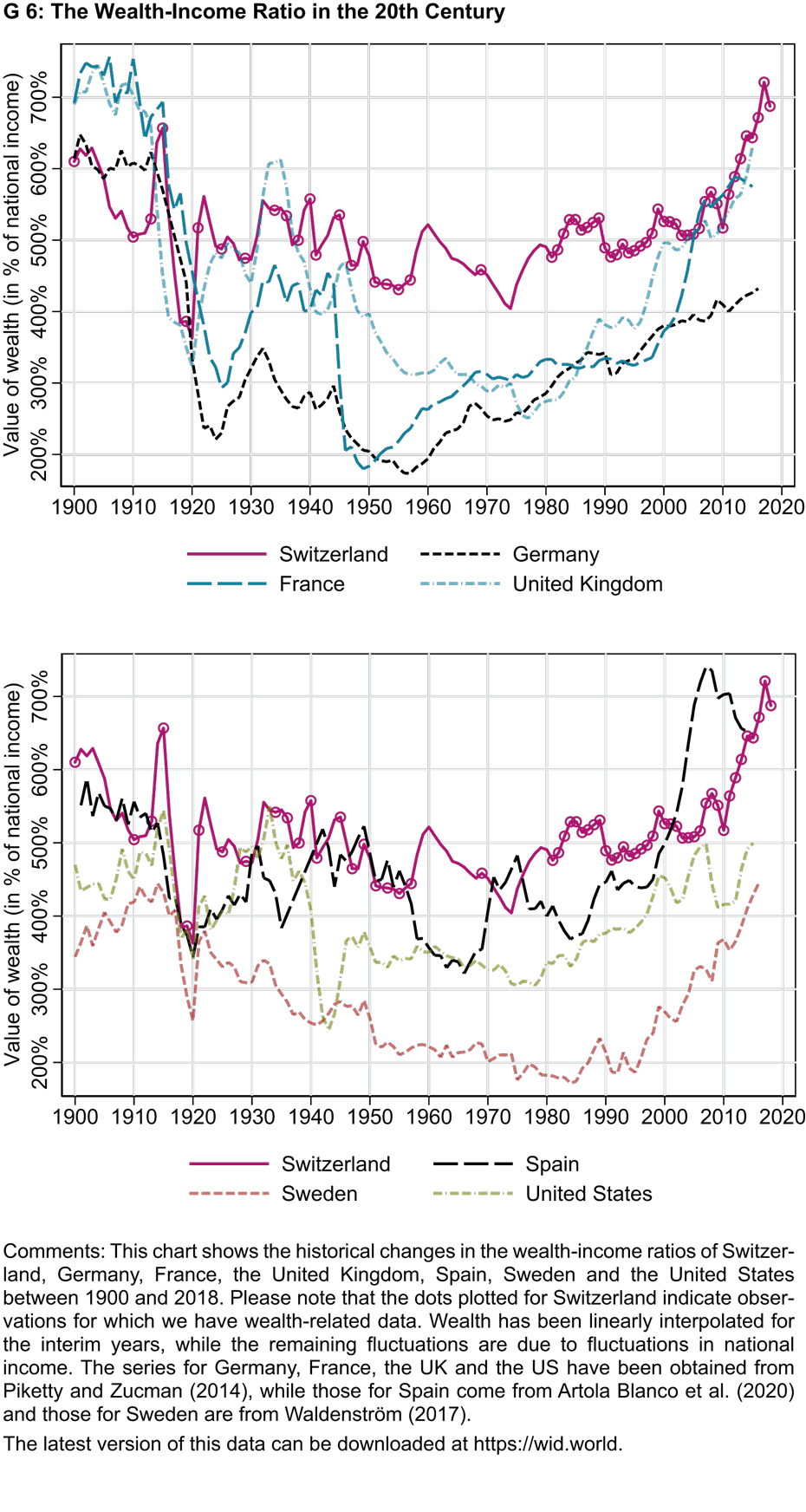

The national net wealth of an economy consists of the sum of private and state net wealth. Data on state assets only exist from 1990 onwards, which is why our historical analysis is limited to the development of private assets. At around 95 per cent, they account for the lion’s share of total assets. Chart G 7 shows the development of Switzerland’s private net wealth (as a percentage of net national income) for the period from 1900 to 2018 in an international comparison.

While Piketty and Zucman (2014) find that the ratio of private wealth to income in old Europe (especially France and the United Kingdom) followed a pronounced U-shaped pattern over the course of the 20th century, the picture for Switzerland is entirely different. Inevitably, a series of economic shocks and significant historical events, such as the First World War and – albeit to a much lesser extent – the Second World War, contributed to substantial fluctuations in Switzerland’s private β over the past century. Chart 1 illustrates, however, that the β of private wealth was more stable in Switzerland than in any other country throughout the entire 20th century. Thus, private β averaged 490 per cent during the period from 1920 to 2005. Previous work also concludes that wealth ratios in Switzerland were relatively stable throughout the 20th century (Dell et al., 2007; Föllmi and Martínez, 2017). Since 2010, however, we have noticed a significant deviation from the long-term trend in the ratio of wealth to income. Aggregate private wealth in Switzerland was equivalent to more than seven years’ income in 2017 – a record figure both historically and internationally.

The importance of state assets

From 1990 to 2018, national net wealth (private + state wealth) as a share of net national income increased from 522 per cent to 742 per cent. This rapid increase can be divided into state assets (from 32 per cent to 55 per cent of income) and private assets (from 522 per cent to 687 per cent). A few things are worth noting here. First, both state and private wealth have grown over the last three decades, with the relative increase in state wealth being much stronger. Second, the rise of 22.5 percentage points (pp) in public net wealth is exclusively due to an increase in the wealth of the cantons (up 17.5 pp) and municipalities (up 7.6 pp), while the federal government (down 1.7 pp) and state social security funds (down 0.9 pp) now hold less wealth relative to net national income than in 1990. Third, the 70 per cent overall increase in government net wealth is remarkable, especially when compared with many other countries where the government wealth-to-income ratio declined sharply over this period, such as Italy (down 81 pp), Germany (down 65 pp) and the United States (down 46 pp). And, fourth, government wealth is nonetheless relatively insignificant in the development of national wealth, as its share of total wealth was still only 7 per cent in 2018.

What explains the rapid increase in the ratio of wealth to income?

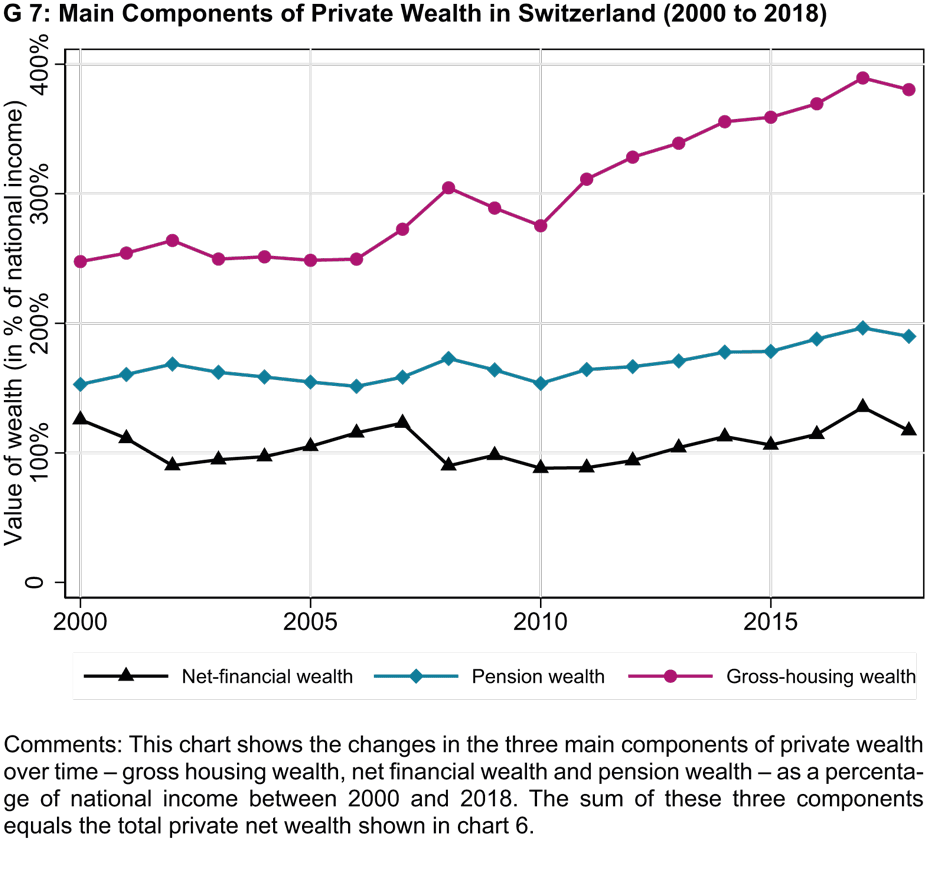

From 2000 to 2018, real national wealth grew by 1,704 billion Swiss francs, 88 per cent of which was due to an increase in private wealth. We therefore restrict our remarks in this section to private assets, which we further break down into the two main components of real-estate assets and net financial assets.

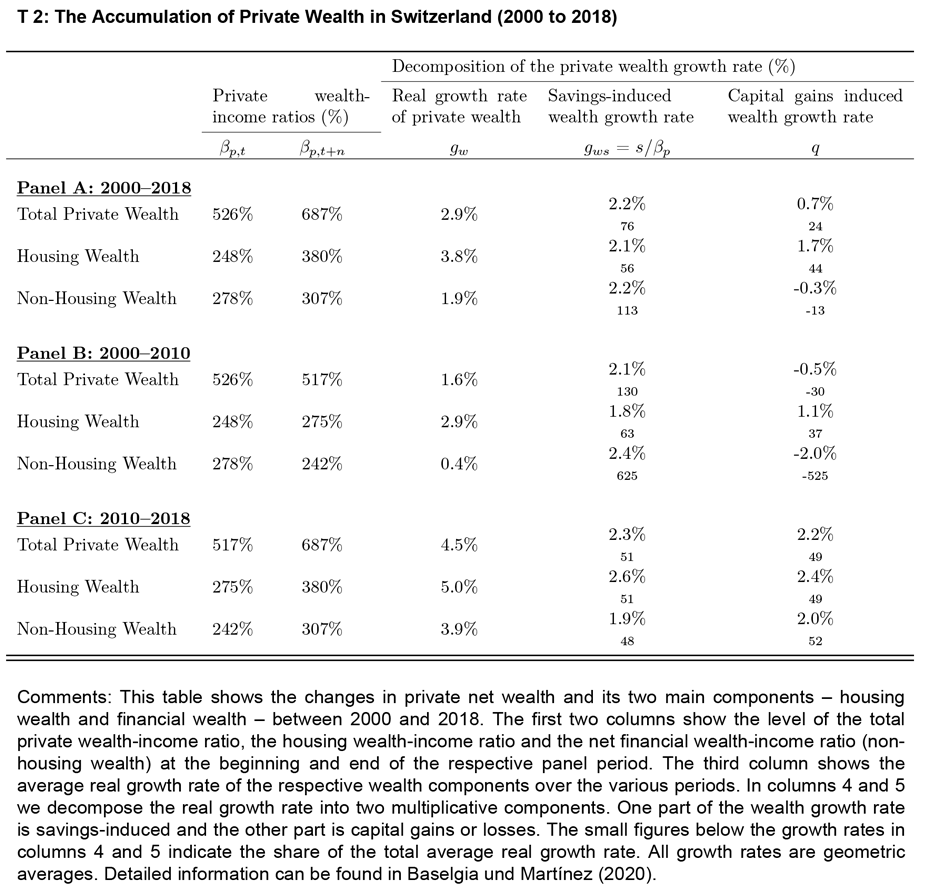

There are basically two possible drivers that could explain the massive increase in private β since 2010: lower income growth (including population growth) and/or faster wealth accumulation. The latter may be the result of higher savings or larger capital gains. In table T 1 we decompose the real growth rate of private wealth – and its two main components – between 2000 and 2018 into a savings component and a capital-gains component.

Real-estate assets grew by 3.8 per cent annually over the period from 2000 to 2018 – twice as fast as net financial assets, which grew at a rate of 1.9 per cent. The savings-induced growth rate of both asset components was roughly the same at 2.1 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively. What distinguishes the two asset classes from each other is the significant capital gains that accrued in the real-estate sector over the entire period, which contributed 1.7 pp (or 44 per cent) to the annual growth rate. In contrast, capital losses have dampened the growth rate of financial assets. The period from 2000 to 2010 was marked by the dotcom bubble and the financial crisis, both of which had a negative impact on financial assets. It was not until after 2010 that substantial capital gains (2.0 pp per year) were again realised on financial assets, so that the previous decline in the financial asset-income ratio was almost completely compensated for.

The rapid growth of real-estate assets accelerated further after 2010, once again driven by capital gains. This trend is especially remarkable because Switzerland is a country of renters. In less than a decade, real-estate assets in Switzerland grew by more than the size of aggregate annual income, about half of which can be attributed to the relative increase in real-estate prices. The substantial capital gains realised between 2010 and 2018 also coincided with a period of extremely weak income growth, which in turn caused an even stronger increase in β.

Conclusions

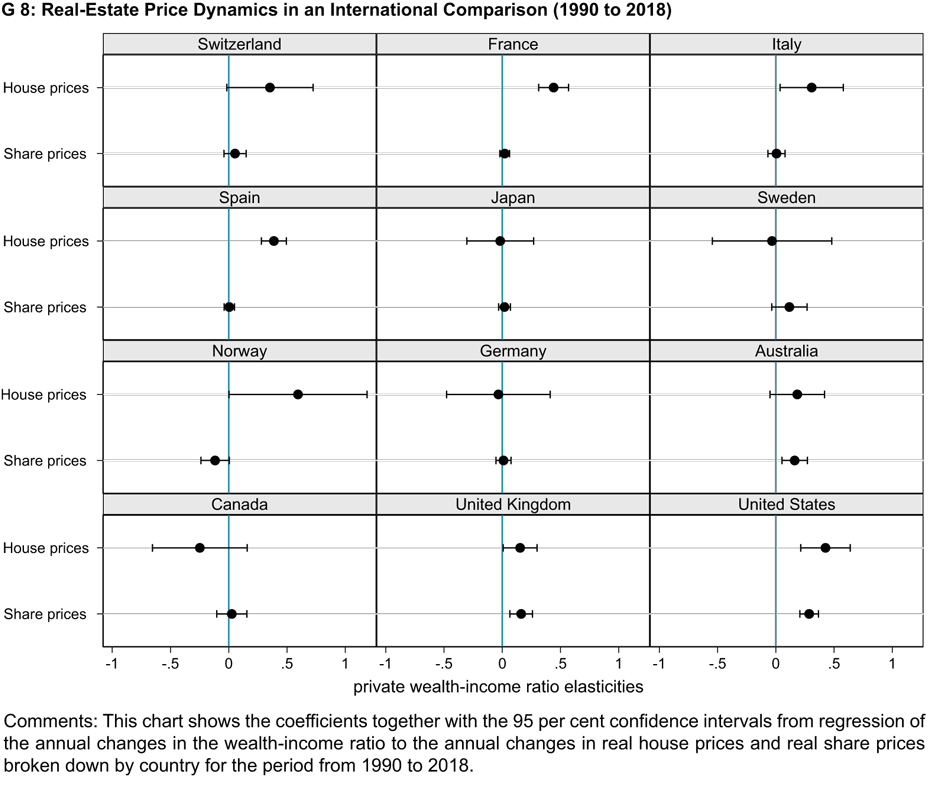

The study shows that the wealth-income ratio in Switzerland remained exceptionally stable throughout the 20th century. Since 2010, however, we have noticed a fairly dramatic deviation from this long-term trend. The sharp rise in the wealth-to-income ratio in the wake of the financial crisis has come about primarily as a result of considerable capital gains, particularly but not exclusively in the real-estate sector. Compared with other countries over the long term, Switzerland resembles the trend observed in Spain, where the significant increase in β was driven by a real-estate bubble (Artola Blanco et al., 2020). The recent levels of the wealth-income ratio can therefore be seen as another possible warning sign that the Swiss real-estate market may be overheating.

References

Artola, Blanco, Miguel, Luis E. Bauluz, and Clara Martinez-Toledano ( 2020): Wealth in Spain, 1900-2017. A Country of Two Lands. The Economic Journal, forthcoming.

Baselgia, Enea and Isabel Z. Martínez (2020): A Safe Harbor: Wealth-Income Ratios in Switzerland over the 20th Century and the Role of Housing Prices. KOF Working Papers No. 487: 1–77.

Dell, Fabien, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez (2007): Income and wealth concentration in Switzerland over the twentieth century. In Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries. eds. by Anthony B. Atkinson and Thomas Piketty, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 472–500.

Föllmi, Reto and Isabel Z. Martínez (2017): Volatile Top Income Shares in Switzerland? Reassessing the Evolution Between 1981 and 2010. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(5): 793–809.

Piketty, Thomas and Gabriel Zucman (2014): Capital is back: Wealth-income ratios in rich countries 1700–2010. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(3): 1255–1310.

Waldenström, Daniel (2017): Wealth-income ratios in a small, developing economy: Sweden, 1810–2014. The Journal of Economic History, 77(1): 285-313.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland