Rising inflation: why is it only temporary, and what does the pandemic have to do with it?

- Inflation

- KOF Bulletin

Prices have risen recently in both the United States and Europe. But much of this price increase can be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic and is therefore likely to be only temporary.

Inflation has picked up – in some cases significantly – in many countries over recent months. In the United States the inflation rate has risen to over 5 per cent, while in the euro area it stood at 3.4 per cent in September. Both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank see price pressures as being temporary (Powell, 2021; Schnabel, 2021). Energy prices, base effects and supply bottlenecks due to the pandemic are driving inflation. But to what extent are temporary supply and demand effects and the price of energy actually contributing to inflation dynamics during the pandemic?

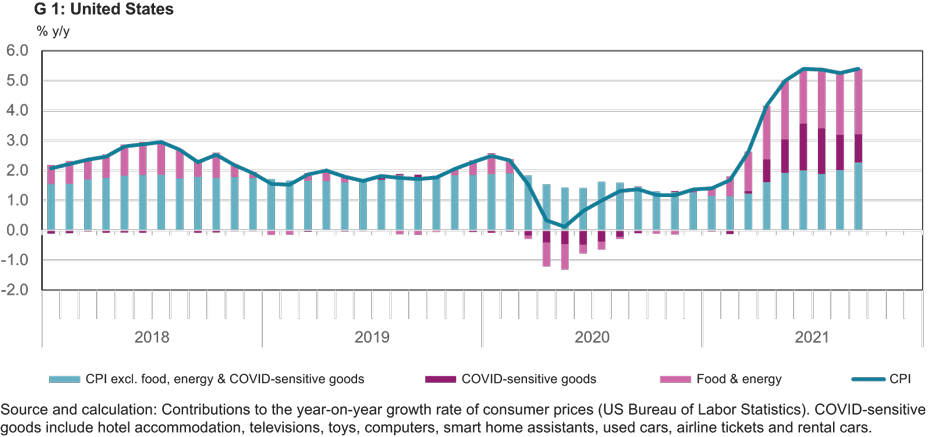

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recently argued in his speech at Jackson Hole that mainly a few goods drive inflation (Powell, 2021). To analyse this, KOF has broken down inflation rates in the US into three components: food and energy, COVID-sensitive goods and core COVID inflation, which makes up the remaining component of the basket (excluding food, energy and COVID-sensitive goods). The COVID-sensitive goods include seven index items that were either in particularly high demand at the start of the pandemic (e.g. computers and televisions), were hardly in demand at all (e.g. hotel accommodation, airline tickets and rental cars) or whose production or supply was temporarily cut back significantly so that there is now excess demand (e.g. used cars).

Inflation in the US is indeed mainly being driven by food, energy and COVID goods (see chart G 1). At the start of the pandemic these goods were still moderating consumer price dynamics. Energy prices fell at the start of the crisis and have returned to normal as the economy recovers, temporarily leading to high year-on-year growth rates. The contributions of other goods have remained much more stable and roughly similar to pre-pandemic levels. This confirms the impression that the currently high inflation rates are being driven by a small number of goods. Rental vehicle prices in May 2021, for example, were up 110 per cent year on year. COVID goods inflation declined slightly back in August, so inflation rates may return to normal in the coming months.

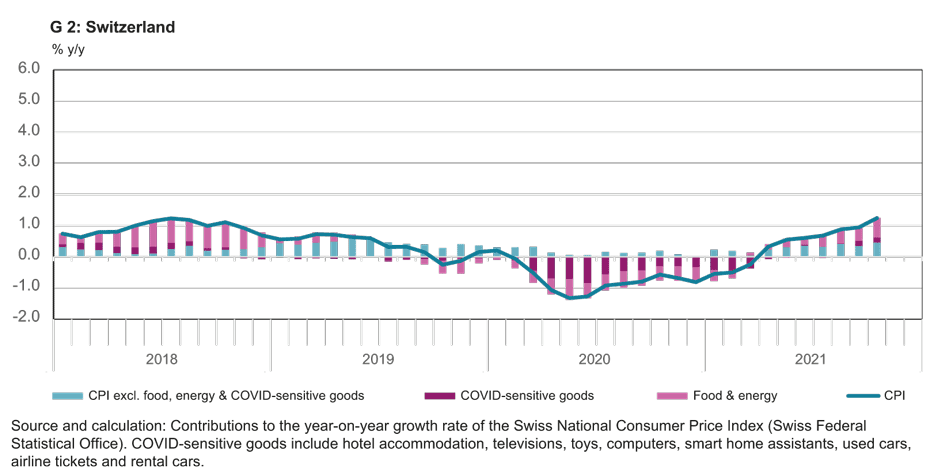

Can the same breakdown also explain the inflation dynamics in other countries? COVID-sensitive goods compressed inflation rates in Switzerland significantly in the pandemic year of 2020 (see chart G 2). The prices of package holidays and air travel, in particular, have contributed to low inflation rates. The prices of these goods have not yet rebounded much in 2021, so there will also be slightly stronger inflationary pressures in Switzerland if these prices return to their pre-pandemic levels. Even then, however, the higher inflation would only be of a temporary nature. The contributions of the remaining goods were positive last year – in contrast to overall inflation – and are rising modestly this year, but they remain at a low level.

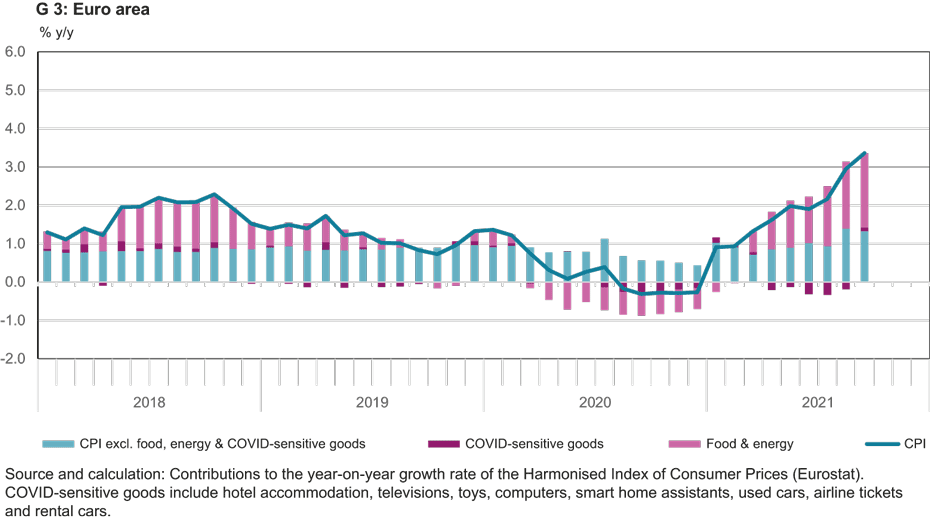

Inflation in the euro area has risen recently, albeit more moderately than in the United States (see chart G 3). The effect of COVID goods in the euro area is less pronounced than in the United States. Energy prices are having a stronger impact on inflation than COVID goods. COVID goods are still making negative contributions, unlike in the US. If we take account of base effects in the wake of the temporary VAT cut in Germany, the COVID core inflation rate also remains relatively stable in Europe and is currently around its pre-crisis level. The economic recovery in the euro area is less advanced than that in the US, which could be partly reflected in a delayed rebound of prices. Although inflationary pressures in Europe are also fairly temporary, it could take a little longer than in the United States for price pressures to ease again.

Consequently, the high inflation rates in 2021 and the low inflation of 2020 actually appear to be driven mostly by temporary effects. Between 50 and 60 per cent of the inflation rate is due to energy prices, food and COVID goods. The high inflation rates in the euro area and Switzerland in particular rather constitute a normalisation of the low inflation rates prevailing during the first and second lockdowns. COVID core inflation rates are relatively stable and remain within the range of pre-crisis levels. Nevertheless, prices may continue to rise if supply constraints persist for longer or if higher inflation translates into stronger-than-expected wage increases.

Literatur

Schnabel, Isabel (2021), New narratives on monetary policy – the spectre of inflation, Speech at the 148th Baden-Baden Entrepreneurs’ Talk, Frankfurt am Main, 13 September.

Powell, Jerome H. (2021), Monetary Policy in the Time of COVID, Speech at the “Macroeconomic Policy in an Uneven Economy,” economic policy symposium in Jackson Hole, 27 August.

Contacts

No database information available

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland