Why do households perceive inflation differently than firms and forecasting organisations?

Swiss households have been asked about their numerical inflation expectations as part of the SECO consumer sentiment surveys conducted since the beginning of 2023. Initial results show that households’ inflation expectations are higher than those of forecasting organisations and firms as well as the official inflation rates. Despite these distortions, the survey data provides valuable information on factors such as the anchoring of inflation expectations.

The prevailing level of prices is not the only key factor in an economy. Expectations about its future performance also play an important role. For example, households’ price expectations are central not only to their investment and saving decisions but also to their purchasing behaviour. In wage negotiations, the individual inflation expectations of both parties form the basis of such talks. Personal perceptions and expectations about current and future price trends therefore affect economic activity. A sound understanding of households’ expectations thus ultimately helps to shape monetary and fiscal policy.

By recently expanding its consumer sentiment survey to include two experimental questions on future inflation trends, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) has created a new data basis to better understand the price expectations of Swiss households and their implications for the economy. To accompany the first publication of the new data, a study prepared by KOF presents initial findings on household expectations and categorises these by using existing results from the literature and other countries (Abberger et al., 2024). Some of these findings are briefly summarised in this article.

Inflation expectations differ between households, firms and forecasting organisations

Subjective perceptions of inflation and expectations vary considerably between individuals and tend to differ from the expectations of firms and forecasting organisations. This is a phenomenon that has long been recognised in the empirical literature. These variations can be identified and reliably documented for various countries and time periods using data from established household surveys (e.g. Arioli et al. (2016) for various European countries).

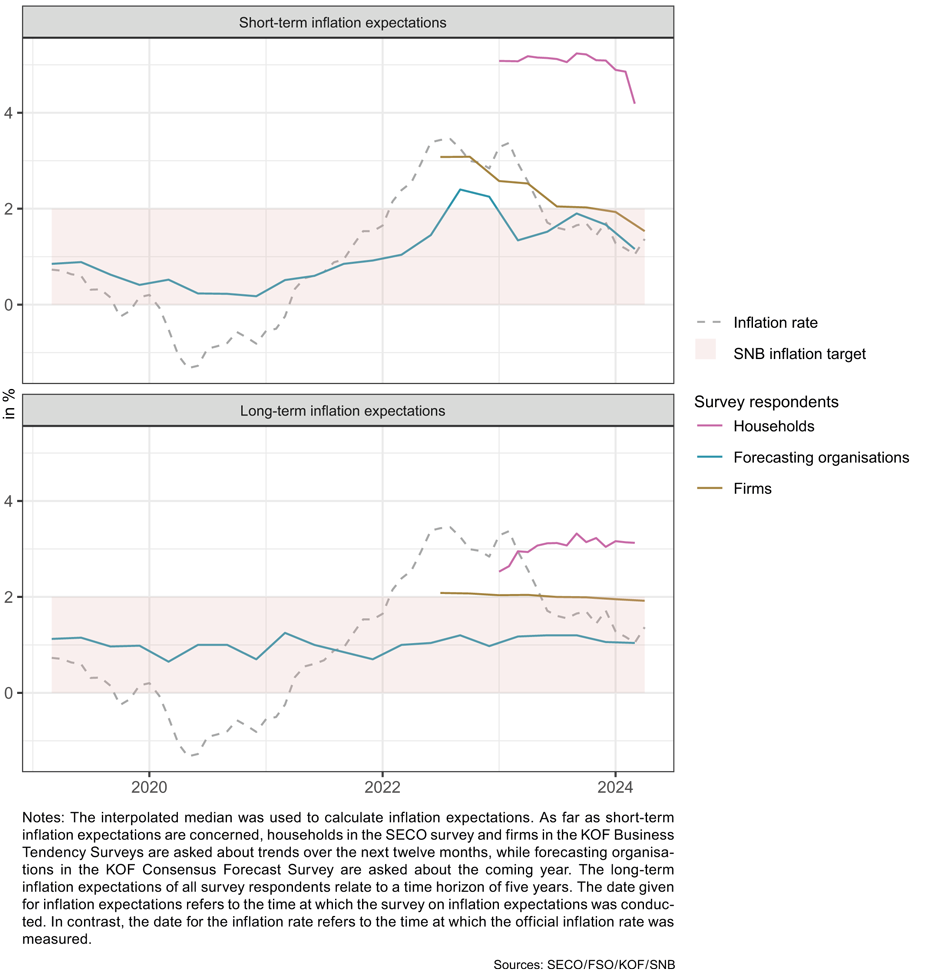

Given this situation, it is not surprising that the new data on the aggregated inflation expectations of Swiss households reveal distortions in terms of excessive expectations. On average, they are significantly higher than the officially published inflation rates and the inflation expectations of other economic agents such as firms and forecasting organisations (see chart G 3).

Consumer habits affect households’ price perceptions

Researchers discuss a variety of hypotheses as to why households’ inflation expectations are distorted. One of the most common explanations is that households perceive certain price signals more frequently than other economic agents owing to their consumption habits and daily activities – as is the case, for example, with food and petrol prices. Consequently, households tend to form their inflation expectations based on the goods and services they consume most frequently rather than on these goods’ share of the total expenditure of the basket of goods on which the national consumer price index is based. Inflation expectations are therefore distorted upwards by changes in the prices of the most frequently consumed goods and services.1

Experience and memories of inflation feed into expectations

Another explanatory approach emphasises cognitive aspects such as experiences and memories as factors that influence expectations about future inflation trends. The literature shows robust evidence across time and space that households overemphasise memories of inflation rates they have experienced themselves (see, for example, Malmendier and Nagel, 2016). People who have experienced high inflation thus automatically have higher inflation expectations than people from generations who have not had this experience.

In addition, households often have a downwardly distorted memory of past prices, which tends to create an exaggerated perception of current inflation. Moreover, people pay more attention to price increases than to price decreases. Even in an environment of low or negative inflation, households often do not expect deflation. This cognitive neglect of price reductions thus contributes to the general distortion of inflation expectations.

Households attach different levels of importance to different types of information when forming expectations

Finally, the selection, weighting and processing of public information that is directly or indirectly related to inflation plays a decisive role in the formation of households’ inflation expectations. Perceptions of current inflation are a particularly important factor in the formation of expectations. In addition, the information channels used by households influence their individual information base, with some attaching more importance to news and press releases from central banks than others.

The more frequent use of traditional media such as newspapers and television is associated with more accurate assessments of past and expected inflation (see Weber et al., 2022). And even the same information is given different levels of attention by different subjects, depending on how much they trust the source and to what extent the new information matches their world view. And, last but not least, each individual has his or her own personal understanding of the information and interprets it differently.

Budget expectations reflect changes in inflation

The fact that households’ surveyed inflation expectations provide valuable signals and information despite distortions is now increasingly becoming a focus of academic literature. D’Acunto and Weber (2024) show empirically that differences in consumption, saving, investment and debt decisions between individuals can be partially explained by differences in their subjective expectations.

Viewed from a macroeconomic perspective, changes in inflation expectations over time should also be of interest in addition to their level. Do inflation expectations react to movements in the actual inflation rate or to monetary policy announcements and adjustments? Households’ short-term inflation expectations, for example, have fallen in line with the downward trend in the actual inflation rate in recent months.

Long-term inflation expectations play an important role in monetary policy analysis, as they provide information on whether inflation expectations are anchored over a longer horizon. In the case of Switzerland, for example, forecasters’ inflation expectations over a five-year horizon are well anchored and have fluctuated only slightly in recent years. This suggests that they viewed the high inflation rates in 2022 and 2023 as a temporary phenomenon and are confident that the Swiss National Bank’s (SNB) price-stabilising strategy will enable inflation to return to its defined target range in the long term.

Although households’ long-term inflation expectations are more volatile than those of forecasting organisations and firms, they fluctuate less than those over a short-term horizon. This suggests that there is a certain anchoring of expectations among households. As the time series of household data is still relatively short, however, it will only be possible to assess this trend and its meaningfulness and anchoring more precisely once further observations are made over the coming years.

------------------------

1This frequency bias has been demonstrated several times in the literature on food prices, for example by D’Acunto et al. (2021).

Info box

In order to best meet the needs of data users, two experimental questions were added to the consumer sentiment questionnaire as part of a fundamental overhaul of the 2023 survey. One of these questions asks households about their numerical price expectations. external page The results are published monthly as an experimental time series on the webpage of SECO.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

References

Abberger, K., Mühlebach, N., Seiler, P., & Siegrist, S. (2024). Study on the Survey of Inflation Expectations in the Swiss Consumer Sentiment Survey. KOF Studies, No. 176. external page https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000658102

Arioli, R., Bates, C., Dieden H., Duca, I., Friz, R., Gayer, C., Kenny, G., Meyler, A., & Pavlova, I. (2016). EU consumers’ quantitative inflation perceptions and expectations: an evaluation (Working Paper No. 038). European Commission.

D’Acunto, F., Malmendier, U., Ospina, J., & Weber, M. (2021a). Exposure to grocery prices and inflation expectations. Journal of Political Economy, 129(5), 1615-1639.

D’Acunto, F., & Weber, M. (2024). Why survey-based subjective expectations are meaningful and important (Working Paper No. W32199). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Malmendier, U., & Nagel, S. (2016). Learning from inflation experiences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1), 53-87.

Weber, M., D’Acunto, F., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Coibion, O. (2022). The subjective inflation expectations of households and firms: measurement, determinants, and implications. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 157-184.