When is state intervention needed?

Automatic stabilisers are normally sufficient to dampen fluctuations in the economic cycle. If the economy slides into a severe recession, however, state intervention is necessary.

If an economy falters, politicians are faced with the challenge of finding a way out of the crisis as quickly and smoothly as possible. But how should this be done and how much government is needed? While some rely on the effect of automatic stabilisers – such as unemployment benefit, the debt brake or income tax – others advocate active state intervention in the form of discretionary fiscal policy, i.e. spending specifically to stimulate the economy. This article deals with the question of why, how and to what extent the state should intervene to stabilise the economy in times of crisis.

Core function of the state

Stabilising the economy is one of the state’s core functions. An economic downturn leads to falling demand, unemployment and lower incomes. The state can take appropriate measures to try to mitigate this downward cycle (and, conversely, the upward cycle) and thereby help to stabilise economic activity. In addition to the short-term positive effects on employment and wages, a stable economy also promotes long-term growth and, consequently, social prosperity. This is because firms – as well as individuals – are more willing to invest appropriately and sustainably in an environment of planning certainty, thereby driving innovation.

An unstable economy, on the other hand, can cause social inequality and tensions, as certain population groups are more affected by economic crises than others. By stabilising the economy, the state therefore helps to promote social justice and economic efficiency.

Expansionary fiscal policy

How can the state intervene to stabilise the economy in times of crisis? It can use expansionary fiscal policy to boost aggregate economic demand: either by increasing government spending or reducing taxes. Both cause the budget deficit to rise. From a theoretical perspective, there are two main arguments for stabilising the economy by expanding government debt in the short term (see Brunnermeier and Reis, 2023).

The first is the neoclassical argument, which is based on the premise that most taxes and government intervention distort behaviour. During a recession, raising taxes or cutting subsidies – which would be necessary to balance the public finances – are probably counterproductive. This is because they would act as a further drag on the already weak economy and exacerbate the recession.

The second is the Keynesian view, which sees recessions as periods during which private saving is too high and therefore private spending is lower than would be socially desirable. If the state increases its spending or lowers taxes, it reduces public saving – and thus overall saving – and brings the economy closer to the desired equilibrium, i.e. full utilisation of economic productive capacity, in which employment, income and tax revenues are above the crisis level that would have occurred without state intervention.

The role of automatic stabilisers

There are a large number of government measures that can be designed as automatic stabilisers on both the expenditure and revenue side. This means that they compensate for fluctuations in economic activity without the need to develop and implement specific policy measures.

The tax system plays a key role on the revenue side. Incomes, corporate profits and sales fall during economic downturns, automatically reducing tax revenues. This lower tax burden can help to stabilise the labour supply, consumers’ purchasing power and corporate investment. Conversely, the higher tax burden during boom phases can dampen economic activity and help to prevent the economy from overheating.

There are also measures on the expenditure side that work in the same direction. These include unemployment benefit, which provides financial support in the event of joblessness. When unemployment rises during economic downturns, the number of people entitled to claim automatically increases. Unemployment benefit maintains their purchasing power. This cushions the decline in disposable incomes and thus stabilises consumption and the economy.

Automatic stabilisers make an important contribution to stabilising the economy without the state having to actively intervene. Their popularity is based on their efficiency, their political independence and their role in promoting social justice. However, they have their limitations. For example, they are not able to respond to all types of economic shocks. These include sudden changes in the international trading environment, such as supply shortages – as recently experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic – and geopolitical events such as wars and oil price shocks. Discretionary fiscal policy measures may be required to stabilise the economy in such situations.

Switzerland’s debt brake

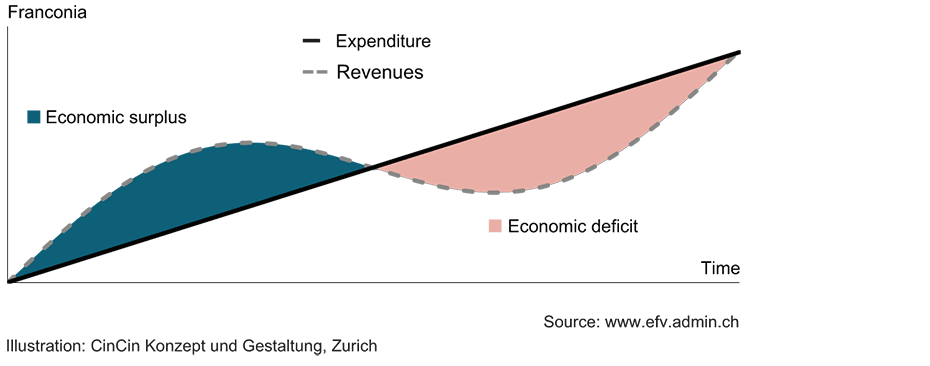

Another automatic stabiliser is the debt ceiling (‘debt brake’), which ensures a balanced (federal) budget over the medium term: ordinary expenditure is limited to the level of structural, i.e. cyclically adjusted, revenue (see chart 1).1

The debt brake plays an ambivalent role in stabilising the economy. On the one hand, it promotes long-term financial stability, which allows leeway for discretionary fiscal policy by keeping gross debt low (see the discussion in Baselgia and Martínez, 2023). On the other hand, it limits the scale of any short-term fiscal policy response during a recession, as ordinary expenditure must not exceed the level of medium-term revenue. The largely rigid design of the Swiss debt brake therefore enables the economy to be stabilised to a limited extent (Kemeny and Wegmüller, 2023). Given Switzerland’s very low level of debt, the question is therefore increasingly whether this ‘strict’ debt brake should be relaxed in order to allow more scope for government investment or tax cuts (cf. Brülhart, 2023). However, special investment funds already exist, and the debt brake permits one-off expenditure in extraordinary situations.2

Discretionary fiscal policy

Automatic stabilisers may not be sufficient to support the economy during severe economic crises. In such cases the state must use discretionary fiscal policy as a last resort and spend beyond the limits of the debt brake in order to stabilise the Swiss economy and prevent it from collapsing. The federal government was forced to offer temporary support to UBS during the financial crisis in 2008. And it issued guarantees totalling around CHF 100 billion and provided extraordinary expenditure of around CHF 30 billion during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Schaltegger, 2021).

The optimal level of state intervention

How much state intervention is appropriate in times of crisis? This question remains a constant challenge for policymakers acting under uncertainty. It is always easier to judge in hindsight whether an economic programme was too cautious or too expansionary. Economic history shows that government interventions have achieved varying degrees of success. Their fiscal stimulus may have been either too little, just right or too much.

It will undoubtedly be difficult to react at the right time and to the right extent during the next crisis. Switzerland can consider itself fortunate to be in a comfortable position now that the COVID-19 pandemic has been overcome. It has a very low level of national debt, which gives it the necessary leeway to be able to respond quickly, flexibly and, if necessary, comprehensively to future economic challenges. It is crucial to maintain this resilience and flexibility in order to ensure the stability and growth of the Swiss economy in the long term while, at the same time, taking social justice concerns into account.

This article first appeared in Die Volkswirtschaft under the title external page Staatseingriffe: Ja und nein (in German).

---------------

1The social security system is not included.

2Transport expenditure is already largely financed from earmarked tax revenue such as the Rail Infrastructure Fund (BIF) and the National Roads and Agglomeration Transport Fund (NAF). These two transport-related funds finance the operation, maintenance and expansion of transport infrastructure.

Bibliography

Baselgia, E., und I. Z. Martínez (2023): external page Wealth-Income Ratios in Free Market Capitalism: Switzerland, 1900–2020. The Review of Economics and Statistics.

Blanchard, O. (2023): Fiscal policy under low interest rates. MIT press.

Brülhart, M. (2023): Ist die Schweizer Schuldenpolitik zu streng? Die Volkswirtschaft. 13 November.

Brunnermeier, M. K., und R. Reis (2023): A Crash Course on Crises: Macroeconomic Concepts for Runups, Collapses, and Recoveries. Princeton University Press.

Kemeny, F. und P. Wegmüller (2023): Wie die Schuldenbremse die Konjunktur berücksichtigt. Die Volkswirtschaft. 14 November.

Schaltegger, C. (2021): Stärkste Stützung der Wirtschaft seit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Die Volkswirtschaft. 25 May.

Contacts

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Director of KOF Swiss Economic Institute

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland