KOF Globalisation Index: Globalisation Down Worldwide in 2015

The level of globalisation fell slightly in 2015. Overall, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Sweden were the most highly globalised countries worldwide. The current KOF Globalisation Index reflects economic, social and political globalisation up to and including 2015.

The level of globalisation worldwide increased rapidly between 1990 and 2007 and has risen only slightly since the Great Recession. In 2015, globalisation decreased for the first time since 1975. The fall was due to the decline in economic globalisation, with social globalisation stagnating and political globalisation increasing slightly.

KOF Director Jan-Egbert Sturm is proceeding on the assumption that globalisation will continue to flat-line into 2016 and 2017, which are not covered yet as data is not sufficiently available for these years. This is apparent in particular from political developments in various Western countries. According to Jan-Egbert Sturm, “Whilst economic globalisation is – given the world economic recovery – likely to have advanced further, in particular the isolationist policy of the USA along with that of the United Kingdom have resulted in greater compartmentalisation”. “I am somewhat sceptical regarding progress in globali-sation”, the KOF Director continues.

The basis for calculating the KOF Globalisation Index has been revised (see box below). A distinction is now drawn between de facto and de jure globalisation. Whereas from the perspective of de jure globalisation the conditions for globalisation improved compared to the previous year, a decline in de facto globalisation is responsible for the fall in the overall index. With regard to economic globalisation it is apparent that in particular de facto globalisation of trade, i.e. the cross-border exchange of goods and services, along with de jure financial globalisation, i.e. the regulatory environment for international financial glows, were responsible for the decline.

Country focus

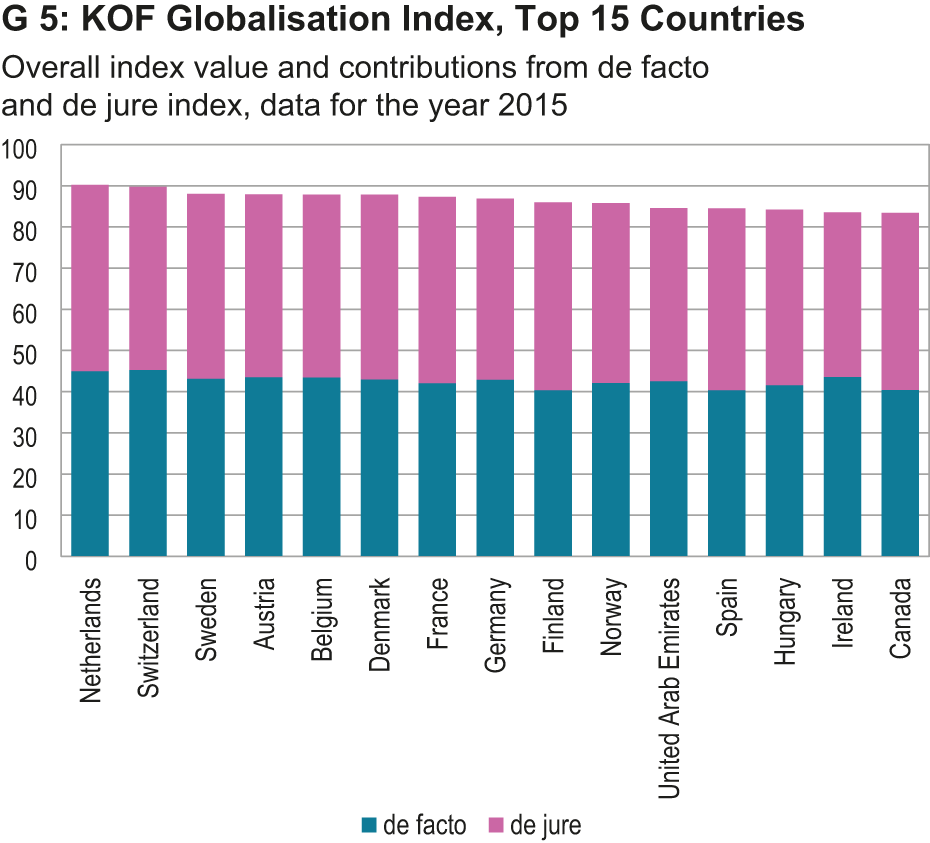

In 2015, the Netherlands was the most strongly globalised country in the world, followed by Switzerland and Sweden. The next places in the ranking were occupied by Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Ger-many, Finland and Norway. The first non-European countries were the United Arab Emirates in 11th place, Canada in 15th place and the United States in 23rd place. The lowest rankings in the table were held by Eritrea, the Central African Republic, the Comoros and Sudan.

Due to their greater degree of interdependence, for example with neighbouring countries, smaller coun-tries tend to be placed higher up in this ranking than larger countries. This leaves the largest national economies around the world in the mid-range. The USA held 63rd position for economic globalisation, as against 29th and 10th for social and political globalisation, respectively. The People’s Republic of China is in the lowest third – 88th in the overall index. Whilst it is ranked in the top 15 for political globalisation, its level of economic and social globalisation is significantly lower. The third-largest econ-omy in the world, Japan, is ranked 36th. Due to their high level of economic, social and political interde-pendence within the EU, the largest European economies – namely Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Spain – are overall much more globalised. Within the overall ranking, France and Germany occupied places 7 and 8, Spain 12th and the United Kingdom 17th. Whilst the United Kingdom achieved a high score in particular for social globalisation, Germany, France and Spain had stronger results for political globalisation.

The emerging economy India achieved very different levels of globalisation in the three sub-domains. Although it is ranked 11th for political globalisation, the level of economic and social globalisation is significantly lower. In these sub-domains India is situated at the lower end of the middle of the ranking.

Economic globalisation

The level of economic globalisation fell back for the first time since the Great Recession in 2009. The decline in economic globalisation was apparent in both sub-domains of de facto and de jure globalisation. This means that not only measured trade and financial flows fell, but also that there was a deterioration in the political framework conditions that facilitate these flows. The decline in de facto globalisa-tion is mainly attributable to the sub-domain of “trade globalisation”, whilst the indicator for “financial globalisation” moved sideways. In terms of de jure globalisation, both sub-domains of trade and financial flows receded somewhat. The most strongly globalised countries are countries that operate as financial hubs and/or trading centres. In 2015 these were, in descending order: Singapore, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Belgium and Malta.

Social globalisation

The level of social globalisation stagnated in 2015 – on the back of strong growth in previous years. De facto social globalisation fell slightly, although compared to de jure social globalisation it was slightly up. In 2015, the front runners in the area of social globalisation were Norway, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Denmark and Ireland.

Political globalisation

In 2015, the level of political globalisation increased overall. The top performer in 2015 in the sub-domain of political globalisation was Italy, followed by France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands.

Methodology

The KOF Globalisation Index measures the economic, social and political dimension to globalisation. It is used in order to monitor changes in the level of globalisation of different countries over extended periods of time. The current KOF Globalisation Index is available for 185 countries and covers the period from 1970 until 2015. A distinction is drawn between de facto and de jure for the Index as a whole, as well as within the economic, social and political components.

The sub-domain of economic globalisation covers both trade flows as well as financial flows. De facto trade is determined with reference to the trade in goods and services. De jure trade covers customs duties, taxes and restrictions on trade.

The sub-domain of social globalisation is in turn comprised of three segments, each with its own de facto and de jure segment. Interpersonal contact is measured within the de facto segment with reference to international telephone connections, tourist numbers and migration. Within the de jure segment, it is measured with reference to telephone subscriptions, international airports and visa restrictions. Flows of information are determined within the de facto segment with reference to international patent applica-tions, international students and trade in high technology goods. The de jure segment measures access to TV and the internet, freedom of the press and international internet connections. Cultural proximity is measured in the de facto segment from trade in cultural goods, international trade mark registrations and the number of McDonald’s restaurants and IKEA stores. The de jure area focuses on civil rights (freedom of citizens), gender equality and public spending on school education.

The sub-domain of political globalisation is regarding the de facto segment measured with reference to the number of embassies and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), along with partici-pation in UN peacekeeping missions. The de jure segment contains variables focussing on membership of international organisations and international treaties.

The Index measures globalisation on a scale of 1 to 100. The figures for the constituent variables are expressed as percentiles. This means that outliers are smoothed and ensures that fluctuations over time are lower. Due to the new methodology, the current Index is only to a limited extent comparable to the old KOF Globalisation Index.

The revised KOF Globalisation Index

The basis for calculating the KOF Globalisation Index has been thoroughly reviewed and revised. A clear distinction within the KOF Globalisation Index is now drawn between so-called de facto and de jure globalisation. Whilst de facto globalisation covers the cross-border flows and activities actually measured, de jure globalisation considers the activities and policies that act as the principal drivers for these flows and activities. Crossborder trade in goods for instance reflects de facto globalisation, whereas customs and other trade barriers fall under de jure globalisation. The distinction between de facto and de jure globalisation is taken into account not only within the overall index, but also in each subcategory of the Globalisation Index. The overall index is calculated from the average of the values for de jure and de facto globalisation.

Another novelty is the distinction between trade and financial globalisation in the sub-domain of economic globalisation. Within the sub-domain of social globalisation, a distinction is drawn between inter-personal globalisation, globalisation of information and cultural globalisation. Cultural globalisation is defined within the revised KOF Globalisation Index in broader terms than it previously was. Whilst in the previous Index cultural globalisation was largely understood as the dissemination of American-Western values, the current definition is not intended to be based on any predefined concept of values. The third sub-domain covers political globalisation.

The selection of the variables that go into the KOF Globalisation Index has been reviewed and expanded. Instead of the previous 23 different variables, a total of 42 are now included. A further change con-cerns the weighting of these variables. Time-varying weighting are now used at the lowest aggregation level of the Index. These weights are determined using a statistical process (principal component analy-sis). Aggregation at higher levels is done using equal proportions.

Find here interactive graphs and detailed rankings.

Contact

No database information available