Measuring Uncertainty

- KOF Uncertainty Indicator

- KOF Bulletin

There are a number of indications that uncertainty has a negative effect on economic development. How can this be measured? As part of a project promoted by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the KOF calculates various uncertainty indicators for Switzerland.

If one were to sum up the current emotional state of the Western world in one word, then "uncertainty" would be a strong candidate for the most suitable description. Uncertainty, or general insecurity, comes in the form of referendums such as the Brexit vote, the chaos of war in the Near East, so-called IS or elections such as the upcoming US presidential contest. Subjectivity and expectations play a major role. Feelings of uncertainty also have negative economic impacts: consumers wait before deciding whether to spend, firms defer investments and the hiring of new staff. However, the precise definition of uncertainty is extremely vague, as is the way in which it can be quantified. For this reason, in a research project financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the KOF is investigating how economic uncertainty can be defined and measured.

In English (as in German), uncertainty clearly has negative connotations. We associate an increase in uncertainty with a rise in the likelihood that the outcome of an event may turn out to be less favourable than expected. In the economic sphere, uncertainty also relates to our expectations. However, economists define it as the variance in our expectations, in the sense that from an economic perspective, an increase in uncertainty raises not only the likelihood of an outcome that is worse than expected, but also of one that is better than expected. This means that an increase in uncertainty also offers opportunities.

Economic actors such as consumers and businesses constantly make decisions and continuously adjust their practices and activities to changing circumstances. On the one hand, businesses and consumers react to actual events: the receipt of an order is normally followed by production and a pay cut normally by reduced consumption. However, as well as reacting to events that have actually occurred, we also react to events that have not yet taken place. A business whose main competitor withdraws from the market will presumably increase its own production in order to be able to deal with any increase in demand. Although the higher demand has not yet arisen for the business, it will start to prepare for the expected increase in demand. This means that we react to changing expectations. In addition, we also react to changes in the variance of our expectations, in the sense that our actions are influenced by changing uncertainty.

Scientific studies show that rising uncertainty can make businesses and consumers more cautious. Businesses decide not to invest and hire staff, whilst consumers spend less. On the level of the economy as a whole, this means that increased uncertainty leads to lower employment and reduced investment. In addition, aggregate private consumption also falls. Uncertainty thus has tangible effects on the real economy.

The causes of uncertainty may often be found in political decisions. Although factors such as natural disasters or terrorist attacks also increase general uncertainty, a major element of uncertainty is rooted in politics. The Brexit referendum in the UK, the initiative against mass immigration in Switzerland or the decision by the Swiss National Bank to remove the exchange rate floor are all examples of how political decisions lead to increased uncertainty.

So how can uncertainty be measured?

Many indications suggest that uncertainty is generally harmful. How can this be measured? In order to minimise uncertainty and to be able to react appropriately to a sudden uncertainty shock, suitable indications are required that can measure the fleeting notion of uncertainty. Various yardsticks have been discussed in the scientific literature: a common indicator of uncertainty tracks the discrepancy between the expectations of businesses over time when questioned in surveys. Further examples include financial market volatility measurements (e.g. the so-called VIX or VSMI), the distribution of forecasting errors by businesses or the discrepancy between the forecasts of professional analysts. At present, the proposal of gauging uncertainty with reference to the number of newspaper articles that use a particular combination of words is given greater credit.

Uncertainty in the media

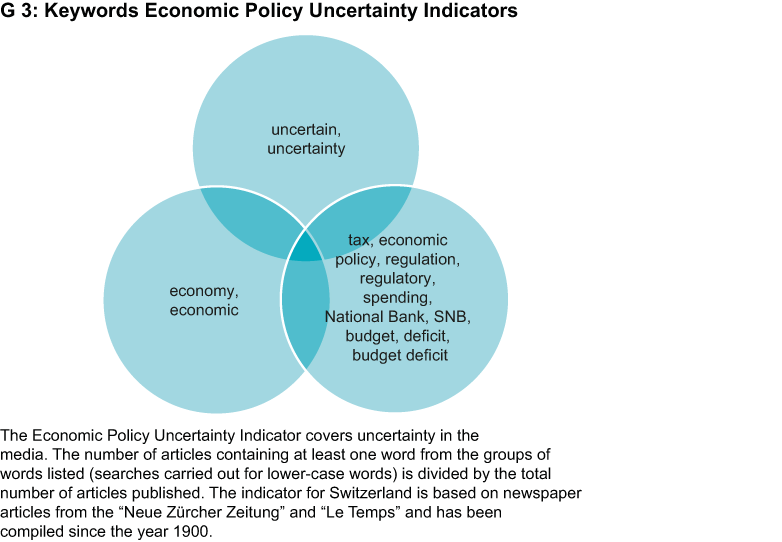

The KOF has recently started calculating all of these uncertainty indicators for Switzerland, as part of an SNSF project. One of the most significant uncertainty indicators is the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which is based on newspaper articles. This indicator is premised on the idea of counting newspaper articles that contain the words uncertainty and economy along with economic policy terms such as taxes, regulation or budget (see G 3). The indicator attempts to portray the perceived uncertainty of an economy and is based on the assumption that newspapers reflect the general mood (sentiment) of the population. The intuitive approach, the immediate availability of data and the long series of historical data make this indicator particularly attractive from an economic perspective. The KOF calculates the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index for Switzerland on a daily basis and publishes indicator figures dating back to 1900. The indicator is based on newspaper articles from the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” and “Le Temps”, whilst also drawing on articles from “La Gazette de Lausanne”, “Le Journal de Geneve” and “Le Nouveau Quotidien” for the pre-1998 period.

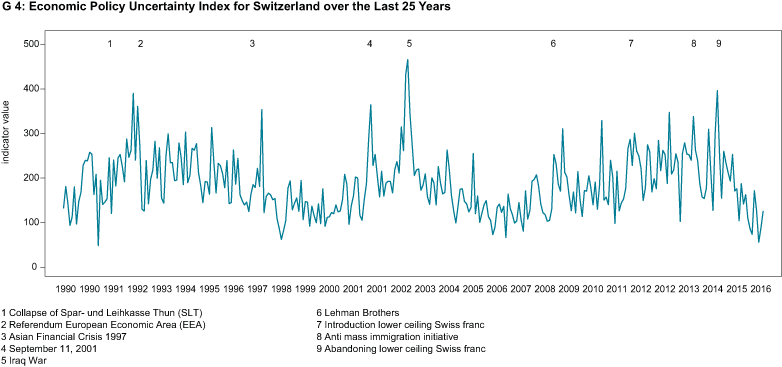

Initial results indicate that a wide array of events over the last 25 years has led to an increase in uncertainty in Switzerland (see G 4). It is apparent that above all the real estate crisis at the start of the 1990s, the 2003 Iraq war and the removal of the Swiss franc exchange rate floor at the start of 2015 led to an increase in uncertainty. However, the Economic Policy Uncertainty Indicator, which is measured against reports of uncertainty in the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” and in “Le Temps”, suggests that uncertainty has levelled out again to some extent over the last few months. Other indicators likewise do not point to an alarming level of uncertainty. This can therefore reassure us somewhat from an economic perspective, which should hopefully also result in a cooling of social, political and civic hysteria surrounding uncertainty.

All our uncertainty indicators are published here.

Contact

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Contact

No database information available