The US-China Trade War: Who Bears the Brunt?

KOF Bulletin

Since 24 Sep. 2018, the US has imposed tariffs on Chinese products worth approx. USD 250 billion, thereby affecting 50% of all US imports from China. While it is often assumed that these tariffs cause direct harm to the US economy, arguments frequently disregard the fact that the US government can impose strategic tariffs which allow it to pursue an optimised customs strategy. This can result both in higher customs revenues and in the generation of welfare gains which are financed by Chinese exporters.

With a considerable proportion of US imports affected by high import duties, it is important to understand the economic consequences and effects. Arguments frequently focus exclusively on the volume of US imports and rarely address the question of who ultimately bears the brunt of the new tariffs. Felbermayr and Zoller-Rydzek (2018a, b) have analysed the impact of the new US tariffs in the context of a simple partial model.

US import duties push up the prices of affected Chinese products in the United States, thereby reducing profit margins for Chinese companies. The spread of this effect depends on relative price elasticity. If consumers’ response to rising prices is weaker than that of producers, the tariffs primarily push up consumer prices. In the opposite case, it is primarily producer prices that decline, for instance because companies forgo their profit margins. This relative effect depends, among other factors, on the availability of substitute goods. The economic literature refers to the spread of the additional tariff burden as ‘tariff incidence’. Tariff incidence is reflected in the relative adjustment of consumer prices and producer prices.

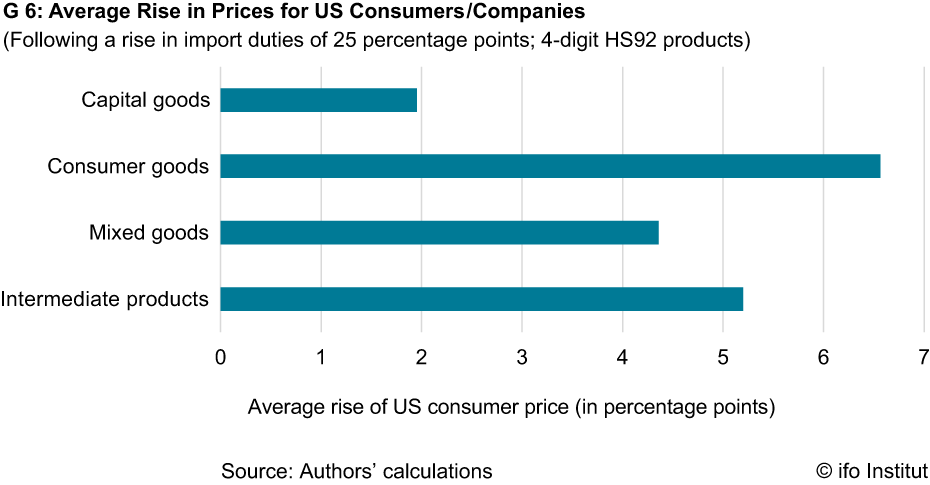

G 6 shows the expected average rise in the price of Chinese products (four-digit HS92) in four main categories. The biggest impact is on consumer goods, whose prices rise by over 6.5 percentage points in the United States. On average, US import prices go up by 4.5 percentage points.

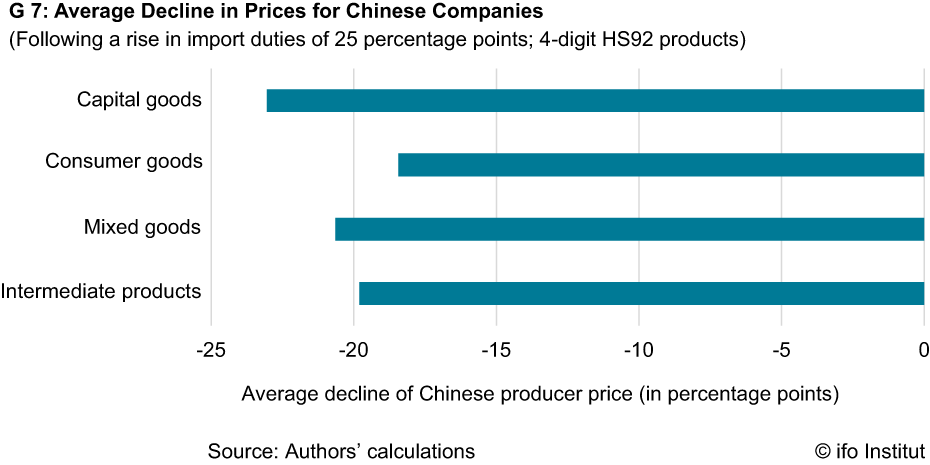

G 7 shows the price changes experienced by Chinese exporters. A large proportion of the burden imposed by import duties is borne by Chinese companies, whose prices fall by over 20 percentage points on average. Such a dramatic decline may motivate some Chinese companies to withdraw from the US market.

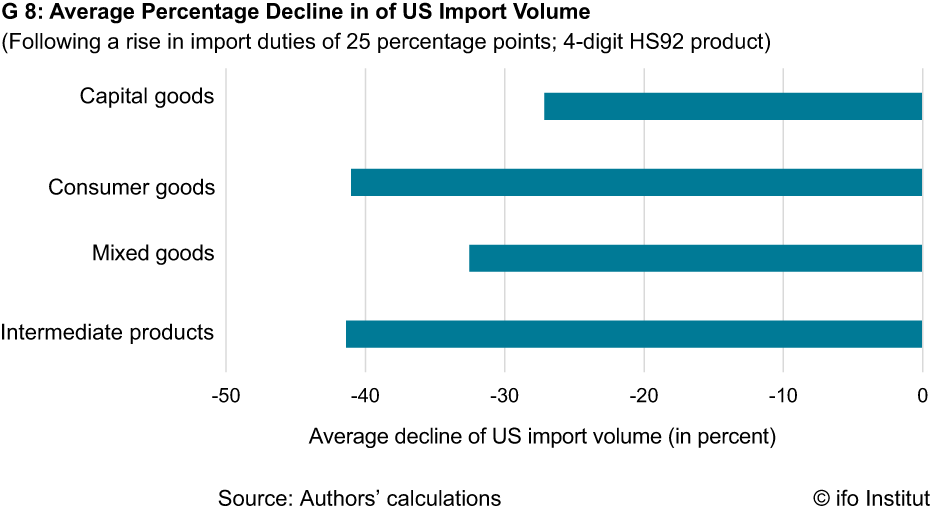

However, it is not only prices that adjust – import volumes also change. Both factors result in lower import volumes from China. Chart 3 shows the average decline in US import volumes as a result of higher import duties. Overall, Chinese imports fall by an average of 37 per cent. Assuming that exchange rates do not adjust, China imposes no punitive tariffs in retaliation and there are no demand effects in third countries, the decline in import volumes would reduce the US trade deficit with China by USD 63 billion to USD 312 billion.

The welfare loss aggregated across all goods in China and the United States amounts to USD 1.6 billion, of which a mere 33 per cent, or USD 522 million, relates to US consumers and companies. However, it should be remembered that a large proportion of the tariffs is not borne by US consumers or companies. Rather, the tariff incidence is mainly borne by Chinese producers. The additional customs revenues of USD 22.5 billion could now be used to compensate for welfare losses among US consumers and companies. With USD 18.9 billion paid by Chinese companies, the resultant net welfare gain for the US economy amounts to USD 18.4 billion.

If the trade dispute escalates, China is likely to impose strategic tariffs in retaliation, resulting in welfare losses in the United States. On top of this, any expansion of the US customs register might lead to a full reversal of the welfare gains in America, as this would then affect products with a less favourable tariff incidence from a US perspective.

The analysis should not be seen as a vindication of Trumpian trade policies. On the contrary: it merely illustrates that opportunistic customs policies following Adam Smith’s beggar-thy-neighbour approach can be successful.

Contact

No database information available