Coronavirus crisis: how does the Swiss labour market compare internationally?

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

Unemployment in Switzerland surged in the first half of the year as a result of the coronavirus crisis. Nevertheless, Switzerland has so far got off relatively lightly by international standards. Unemployment in Switzerland has risen less sharply than in the UK or Canada, for example, but slightly more than in Sweden or Germany. The example of Sweden shows that the crisis has hit the labour market hard even in cases where the authorities have not ordered a lockdown.

The coronavirus crisis caused an unprecedented rise in Switzerland’s unemployment in March and April. Adjusted for seasonal fluctuations, the number of people registered as unemployed at regional employment offices rose by no fewer than 50,000 in these two months, according to the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO). In total, the seasonally adjusted rate of registered unemployment at the end of May was 3.5 per cent, compared with 2.3 per cent at the end of February. This means that, in just three months, registered unemployment rose almost as sharply as in the first ten months of the financial and economic crisis in 2009.

Just over two-thirds of the increase in the number of unemployed was due to people joining the ranks of the jobless – because, for example, workers were made redundant or their contracts were not renewed. One-third of the increase was due to a sharp drop in the number of people leaving unemployment. The crisis has meant that many firms have stopped recruiting staff, making it very difficult for the unemployed to find suitable jobs. Fortunately, in May – once the restrictions had gradually been eased – unemployment rose by only a third as much as in the two previous months. The end of the lockdown has slightly reduced the impact of the crisis on the labour market.

Coronavirus crisis destroys many jobs worldwide in a very short time

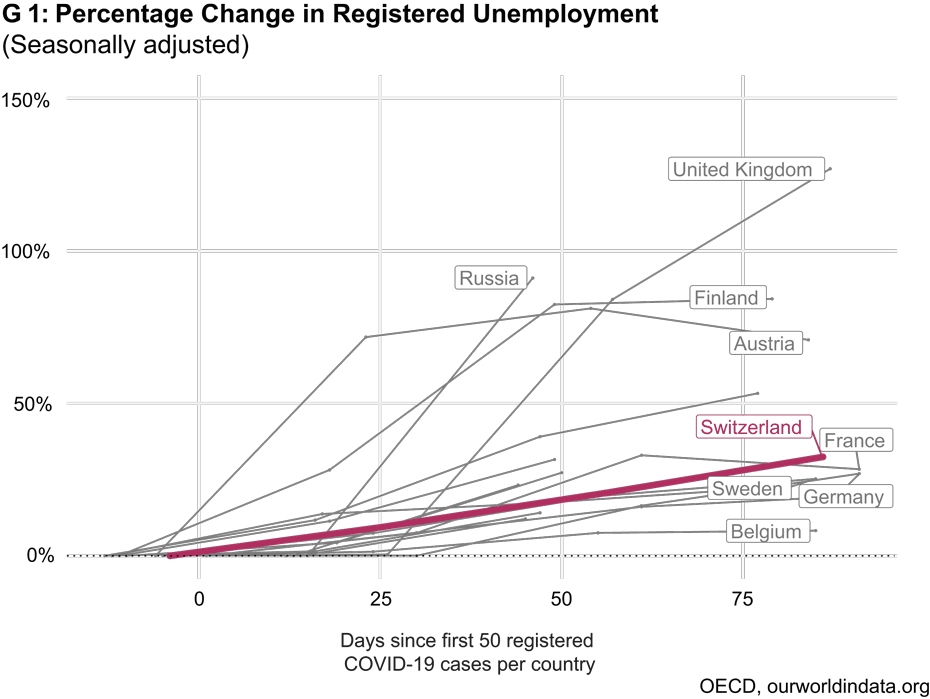

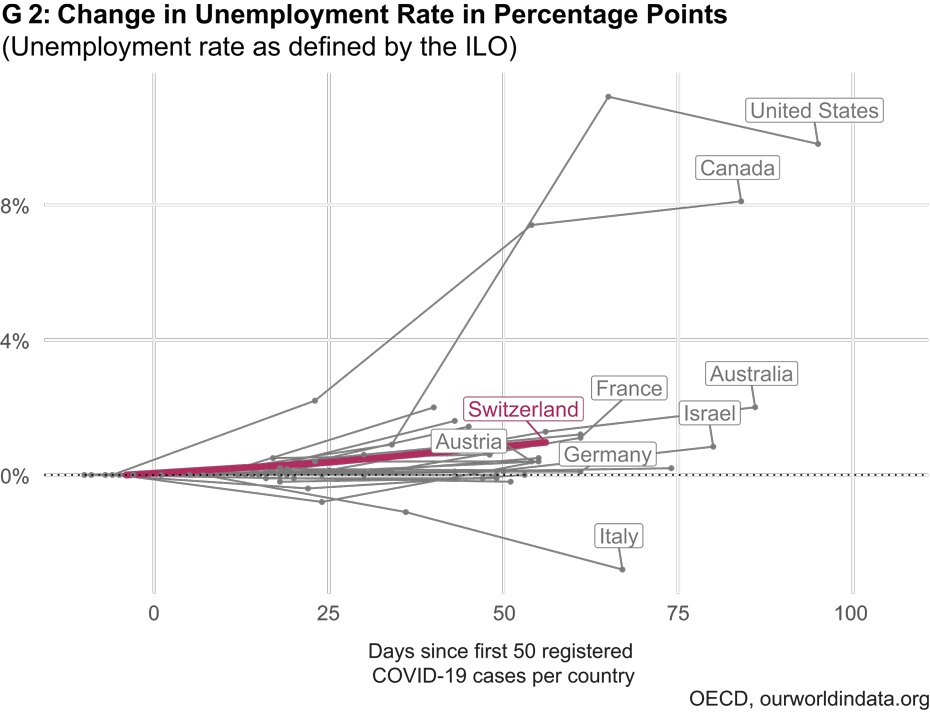

Switzerland is not unique with its unprecedented rise in unemployment in the first few months of the pandemic. The crisis has destroyed a great many jobs in virtually all economies of the world within a very short time. The charts below show the rise in unemployment across various countries based on OECD data. Drawing on the now familiar infection curve, the charts illustrate the growth in unemployment relative to the day on which the 50th COVID-19 case was reported in a country (the month before the 50th case was reported serves as a reference point).

The two charts differ in the way that unemployment is measured. Chart G 1 shows the increase in the number of registered unemployed – i.e. those jobless individuals who are registered with the public employment service according to national statistics. The figures are very reliable and are usually available in real time, as they are derived from register data. However, measuring unemployment on the basis of registration has several drawbacks. For example, a country with a generous unemployment insurance scheme has virtually by definition more people registered as jobless than a country where unemployment benefits are very low or very time-limited. The level of registered unemployment is therefore not internationally comparable. Consequently, the chart shows the percentage increase in unemployment compared with the day on which the 50th COVID-19 case was reported.

In addition, the second chart shows the changes in the unemployment rate as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO). These figures are internationally comparable and are based on internationally harmonised monthly or quarterly surveys of households. In Switzerland the unemployment rate calculated in this way is often referred to as the jobless rate and is determined by the Federal Statistical Office. In this case, the chart focuses on the increase in the unemployment rate in percentage points. We are interested in how the number of unemployed has changed in relation to the number of people in the labour force. The Swiss figures, which are only published quarterly, have been updated in the chart using the SECO figures up to the end of April.

Rise in unemployment is about average

Both charts show that Switzerland has so far seen an increase in unemployment that is roughly in line with the average for the countries being surveyed. Since the 50th COVID-19 case was reported, the seasonally adjusted number of registered unemployed has risen by approximately 32.5 per cent according to OECD figures. Although this increase is higher than that in Belgium, Sweden and Germany, it is much lower than in the UK and Russia. Looking at the figures as defined by the ILO, it is also apparent that Switzerland has got off much more lightly in terms of unemployment than the United States and Canada.

Several factors might explain the differences in unemployment growth between countries. This includes, firstly, the sectoral structure of a country, as countries with a large tourism industry such as Austria tend to be more seriously affected. The extent to which a country is affected by the pandemic and the countermeasures taken by the authorities also play a role. The example of Sweden shows that the coronavirus crisis is having a severe impact on the labour market, even though the authorities have not ordered large-scale closures of businesses. Here, registered unemployment has risen to a similar extent as in Switzerland since the 50th COVID-19 case was reported. The international interconnectedness of economies means that this crisis will have a significant impact on labour markets even in cases where the authorities do not order a lockdown.

Widespread use of short-time working in Switzerland

However, the most important factor in explaining these international differences is the instrument of short-time working. In countries such as Russia, Canada and the US, which do not have any system of short-time working, the lockdown and its economic effects have caused huge increases in unemployment. In countries such as Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, Italy, France and Sweden, short-time working has so far largely prevented many redundancies. By the beginning of June in Switzerland, for example, cantonal permits to receive short-time working benefits had been granted to 1.6 million employees in March and 1.9 million in April. This means that, at the peak of the crisis, more than a third of Swiss employees were affected by short-time working, so the use of this instrument in Switzerland is likely to be at the upper end of the scale on an international comparison, according to OECD data.

The example of Italy illustrates the pitfalls of using the ILO definition to measure the unemployment rate. According to the chart, the unemployment rate in Italy fell significantly despite the fact that the country was hit particularly hard by the pandemic. However, this decline in unemployment is measurement-related: since February, the number of economically inactive 15- to 64-year-olds – i.e. those who are no longer actively participating in the labour market because they are not attempting to find work – has increased by at least 3 percentage points, according to data from the National Statistical Office. Consequently, the unemployment rate measured according to the ILO definition has actually fallen, as the unemployment numerator only includes people who are participating in the labour market. This phenomenon should be taken into account in the next publication of the ILO’s unemployment figures for Switzerland as well. A representative survey of jobseekers in Switzerland showed that many of these individuals were significantly less active in their job search during the lockdown period owing to a lack of suitable job advertisements or that they had even discontinued their search efforts altogether (Lehmann et al., 2020).

Employment rate likely to remain below average for some time

The above charts allow an initial assessment of how the coronavirus crisis has impacted on national labour markets. However, this crisis is far from over. This also applies to the Swiss labour market, which continues to be underutilised from a historical perspective. Many companies can ramp up their operations simply by increasing the working hours of existing employees who are on short-time working. The lack of job vacancies will make it difficult for many unemployed people to find work, which is why the aggregate employment rate resulting from unemployment is likely to remain below average for months to come.

In addition, there is a risk that the recession in the global economy and the permanent consequences of the crisis for consumer behaviour will lead to business closures and mass redundancies in certain sectors in the second half of the year. Consequently, many individuals who currently still have a job or are on short-time working are likely to lose their jobs in the coming months. Accordingly, KOF is predicting in its economic forecast that the unemployment rate in Switzerland will continue to rise in the second half of the year.

References:

Michael Siegenthaler (2013): external page Die «Erwerbslosenquote» ist die eigentliche Arbeitslosenquote, Ökonomenstimme.

Lalive, Rafael, Tobias Lehmann, und Michael Siegenthaler (2020): external page Die Schweizer Stellensuchenden im Covid19-Lockdown.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland