How did short-time workers use their additional free time?

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

At the height of the coronavirus crisis, 1.35 million individuals in Switzerland were working short time. A recent special study by KOF looks at how those on short-time working used their extra free time in 2020.

Short-time working was probably the most important economic policy instrument used to limit the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market. As comparisons with other countries that have no short-time working arrangements suggest, there would have been an unprecedented wave of redundancies in Switzerland in 2020 if short-time working had not been available. At the height of the coronavirus crisis in April 2020 – when many shops and all markets, restaurants, bars and entertainment and leisure businesses had to remain closed – short-time working arrangements were made available to no fewer than 1.35 million individuals in total, which was almost 15 times more than at the height of the financial and economic crisis in 2009.

A new KOF special study conducted by Alexander Götz, Daniel Kopp and Michael Siegenthaler examines the question of how short-time workers used their additional free time in 2020. Did they take on a second job? Did they continue their education or look for another job? Did they do further unpaid work, for example by spending more time on childcare or gardening? The answers to these questions are important partly because they provide clues as to how ‘productively’ short-time workers used their additional free time.

To investigate these questions the authors used data from the Swiss Labour Force Surveys (SLFSs) for the years 2019 and 2020. Their study also benefits from the fortunate fact that households were asked in detail about the extent of their unpaid work as part of a special module completed in 2020. Short-time workers can be identified in the relevant data because respondents who worked less than contractually required during the week preceding the survey are asked about the reasons for their reduced working hours. Short-time working is one possible answer.

Full-time employees on short-time working gained an average of 3.5 hours per working day

The analysis provides a number of interesting findings. Firstly, the data suggest that short-time workers had additional free time between April and December 2020 owing to their reduced workload. For example, full-time employees on short-time working had an additional 3.5 hours of free time per working day. The loss of working hours was significantly greater during the lockdown than in the two quarters of the second half of 2020. Many short-time workers did not work at all between April and June.

Secondly, the analysis shows that short-time workers did not take up more secondary employment during the crisis. On the contrary, short-time workers were less likely to take on second jobs than before the pandemic. This decline is probably primarily a reflection of the reduced chance of finding employment during the crisis. This assumption is supported by the fact that the likelihood of taking on a second job also fell slightly among those who remained fully employed in their main jobs.

Less time for job searches during lockdown

Thirdly, the analysis shows that people who were on short-time working in the second quarter of 2020 – i.e. during the lockdown – were less likely to look for a job than they were before the pandemic. This, too, is likely to be mainly because there were few job vacancies during the lockdown, which is why looking for employment made little sense in many segments of the labour market. Accordingly, job searches also declined among the employed who did not have to go on short-time working. Only in the second half of 2020 did job searches by those on short-time working increase somewhat. Overall, however, just a few short-time workers – only around 12 per cent of the total – looked for a new job. Roughly 8 per cent of these workers were already looking for a job before the pandemic.

Fourthly, the surveys suggest that both employed individuals and short-time workers were significantly less likely to have attended a continuing education course or seminar in 2020. The decline compared with pre-pandemic levels was particularly pronounced during the lockdown. However, fewer such courses and seminars were attended in the second half of the year as well. Only those who became unemployed during the crisis were more likely to undertake further training in the second half of the year than they were before the pandemic. The general decline in continuing education and training (CET) activity is probably mainly due to the fact that many CET courses were no longer allowed to be held in 2020.

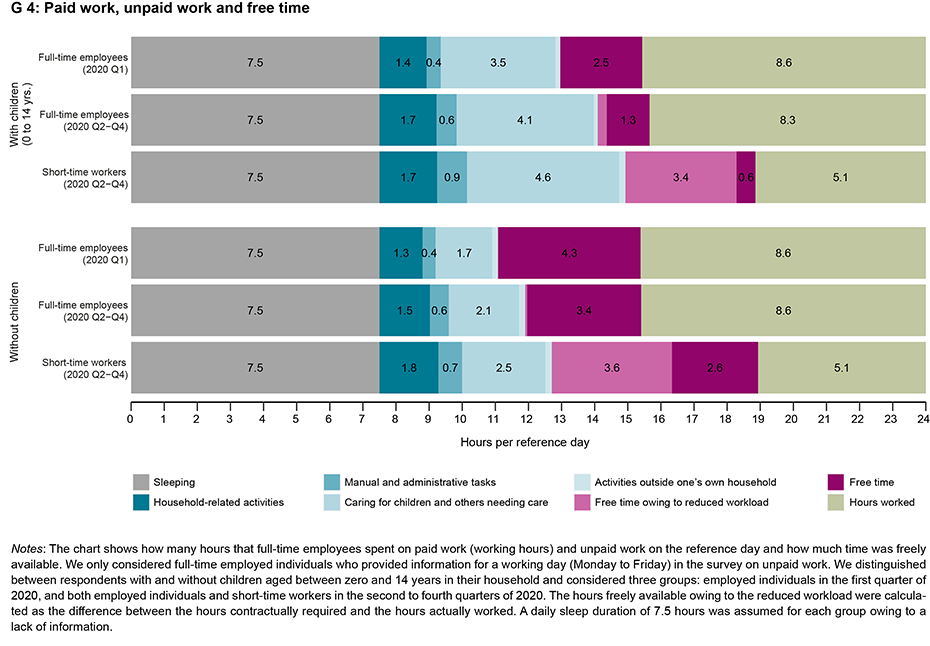

The analysis thus suggests that most of those on short-time working did not primarily use the time they had freed up in order to take up secondary employment, look for a new job or attend a further training course. Did they instead perform more unpaid work? We explore this question in chart G 4. As an indication of how much unpaid work is normally done by full-time employed individuals, we used the responses of employed people who were interviewed just before the outbreak of the crisis. We compared these answers with the responses of those who were either on short-time working or still fully employed during the crisis. In order to reduce the likelihood that differences between groups are due to different employment levels, we only considered full-time workers. We also distinguished between respondents with and without children aged zero to 14 in their household.

The chart first illustrates – by means of the red bars – how much time the various groups had at their disposal per working day. Immediately before the crisis this was an average of 2.5 hours for employed individuals with children aged under 14 and 4.3 hours for those without children in this age group. Free time during the COVID-19 pandemic decreased by about one hour for employed people both with and without children. On the other hand, full-time employees on short-time working had slightly more free time since they did fewer hours of paid work owing to their reduced workload and did not fully compensate for this by doing unpaid work. Short-time workers with children aged under 14 had about four hours of free time, while those without children had slightly more than six hours.

Working from home and home-schooling changed people’s daily routines

Unpaid work increased across all groups considered during the pandemic compared with the first quarter of 2020. The time spent on household-related activities such as preparing meals, washing up, setting the table, shopping, cleaning, tidying up and washing laundry increased by an average of around 0.3 hours per day. The time spent on manual and administrative tasks – including gardening – grew to a similar extent. The time spent on childcare and other individuals in need of care increased even more during the pandemic. These findings can probably be attributed to the increase in working from home and the fact that some children had to be home-schooled during the lockdown.

However, it is also striking that unpaid work increased particularly sharply among those on short-time working. Short-time workers with children, for example, spent 0.3 hours more on manual and administrative tasks than full-time employees with children who were able to continue working during the pandemic without short-time working. Short-time workers with young children spent half an hour more on caring for children or dependants than this group. Overall, the analysis suggests that short-time workers spent about one-third of their lost working hours on additional unpaid work.

The full version (in German) of this article is available here.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

ETH Zürich

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle