What progress has been made on gender equality in the labour market?

- Labour Market

- Inequality

- KOF Bulletin

The main reason for the persistent gender differences in the labour market is the unequal distribution of unpaid work. This leads to women doing less work than men, which has a negative impact on their performance in the labour market.

Since 1971, when Swiss women finally got the right to vote and stand for election, much has happened in terms of gender equality. For example, the proportion of women on the National Council has risen from 0 per cent to 42 per cent. And the labour market has also become more female. The labour force participation rate among women has increased from 43 per cent in 1971 to 63 per cent in 2019, while the male labour force participation rate has decreased from 86 per cent to 74 per cent over the same period. In Europe, only Iceland has a higher female employment rate than Switzerland (data sources: Swiss Federal Statistical Office; Head-König 2015). And yet many women did not really feel like celebrating on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage. Far from it: tens of thousands of women throughout Switzerland took to the streets as part of the so-called ‘women’s strike’ on 14 June 2021, denouncing the persistent gender differences in the labour market and other areas of life.

Dispute over the unexplained pay gap

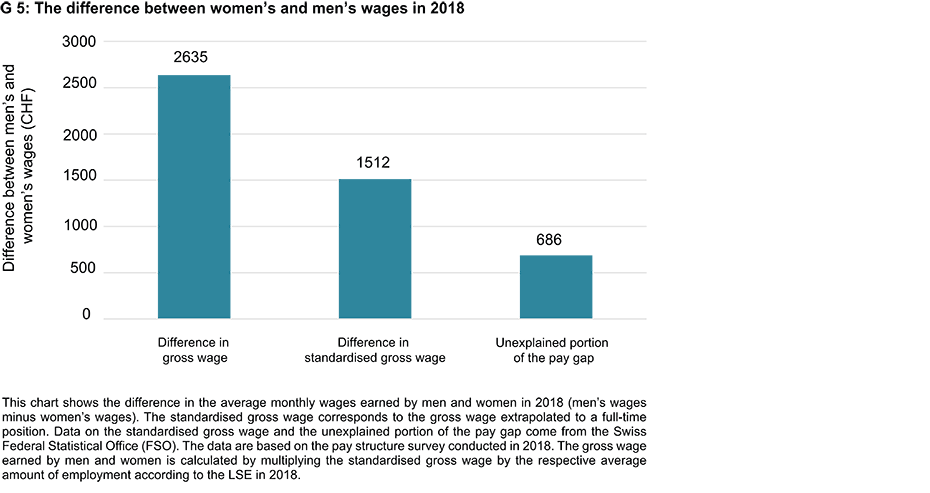

The political and media-led debate about gender differences in the labour market often revolves around the so-called unexplained pay gap. To arrive at this figure, the average wage earned by both men and women is extrapolated to a full-time position and the difference is divided into two parts: a portion that can be explained by objective factors such as education, work experience, sector, company size and hierarchy level, and an unexplained portion. The unexplained portion quantifies the pay gap between men and women who otherwise possess the same attributes and work in similar jobs. The Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) found in 2018 that around 55 per cent of the standardised (i.e. extrapolated to a full-time job) pay gap of CHF 1,512 could be explained by objective factors, while 45 per cent of the pay gap remained unexplained. This unexplained part is often interpreted as discrimination. Whether this interpretation is correct or not is the subject of intense debate.

One side in this debate complains that certain wage-relevant information is missing from the data and that discrimination therefore tends to be overestimated. Indeed, it is possible that the unexplained pay gap would be reduced if previously unobserved factors such as attendance on further education courses or effective work experience were taken into account. The other side in the debate, on the other hand, complains that the methodology used underestimates rather than overestimates actual wage discrimination since some of the supposedly objective factors are also the result of discrimination. This upstream discrimination is not captured by the unexplained pay gap. This criticism is justified. By treating hierarchy level as an objective factor, for example, the methodology used ignores the fact that it is presumably much more difficult for women to advance to higher hierarchy levels than for men (cf. e.g. Cullen and Perez-Truglia 2019).

The adverse effects of small workloads

There is a danger that other important dimensions of gender inequality will be lost in the sheer noise of debate about the unexplained pay gap. But gender inequality stems not only from the fact that women earn less than men for doing the same job but, primarily, from the fact that they do different jobs. Consequently, according to the FSO, the unexplained pay gap in 2018 was CHF 686 per month. However, the total pay gap between men and women amounted to around CHF 2,630 (see chart G 5). Around CHF 1,100 of this pay gap (the difference between the gross wage and the standardised gross wage) can be fully explained by men’s and women’s different average employment levels. Thus, whereas almost 60 per cent of all women worked part-time in 2019, just under 18 per cent of men did so.

A large proportion of the remaining pay gap is also indirectly related to the different workloads. Part-time work is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it offers the opportunity to balance work with family responsibilities. The high proportion of part-time working among Swiss women is probably an important reason for their high employment rate. At the same time, however, part-time work entails numerous disadvantages. Not only does it yield lower incomes but it also massively reduces the chances of advancement in a firm. This is because managerial positions still often involve working full time. In 2019, 86 per cent of all employees in managerial roles at companies with more than 50 employees worked full time (calculations based on the Swiss Labour Force Survey). This is probably one reason why women are still strongly underrepresented in managerial positions. In 2019, only 27 per cent of all employees on the management boards of companies with more than 50 employees were women.

However, part-time work also means that certain segments of the labour market are inaccessible. Many highly paid jobs such as in management consultancy, the financial sector and corporate law either implicitly or explicitly require very long working hours. These highly remunerated jobs remain out of reach for those who are not willing or able to work such long hours (cf. Goldin 2014). And, finally, part-time work provides a lower level of social security. This is especially true of the so-called ‘second pillar’ of the Swiss welfare system, where the coordination deduction and the entry threshold ensure that very little retirement capital is saved by those who work part time. A direct consequence of this system is the significantly lower pensions paid to women under the second pillar. The FSO’s latest statistics reveal that the median old-age occupational pension paid to men is CHF 2,144 per month, which is almost twice as high as that paid to women (median of CHF 1,160 per month).

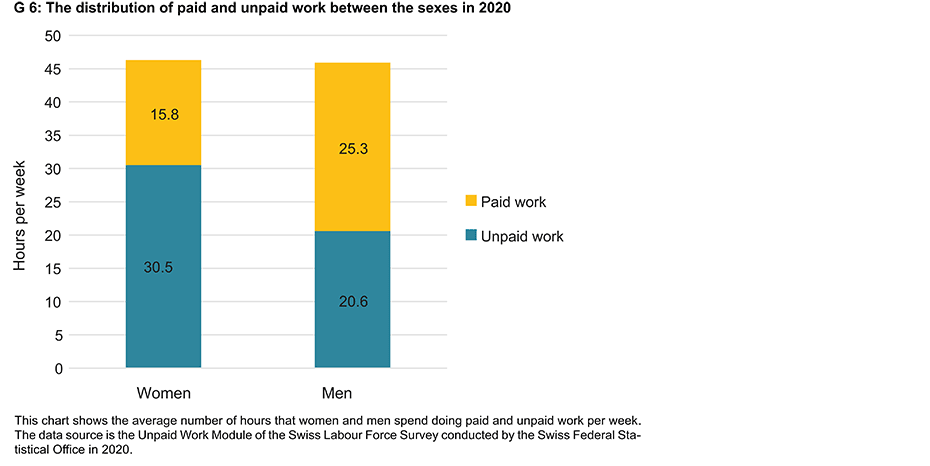

The private is economic

The main reason for the large gender gap in employment levels is easy to identify: women still do most of the unpaid work. This includes raising children, caring for family members, preparing meals, cleaning and gardening. According to the FSO, women spend around 30 hours a week doing unpaid work while men spend around 20 hours doing so. This ten-hour differential corresponds exactly to the difference in the number of hours that men and women spend on paid employment (see chart G 6). The unequal distribution of unpaid work is the main reason for the gender gap in the labour market. It means not only that women work part time more often but also that they take more frequent career breaks – especially after the birth of children. Studies show that such career breaks have a highly detrimental impact on women’s progress in the labour market (Bertrand et al. 2010). Moreover, because women still often bear most of the responsibility for raising children, they have to take jobs closer to home. This reduces the supply of available employment and can mean that women are forced to accept lower-paid jobs (Petrongolo and Ronchi 2020).

The most plausible reason for the unequal distribution of unpaid domestic work is the persistence of traditional gender stereotypes – not only among jobseekers but also on the part of employers. A study of the behaviour of recruiters selecting candidates on an online employment exchange shows that men looking for a part-time job are penalised much more than women who want to work part time when it comes to getting a job interview (Kopp 2021). If gender inequality in the labour market is to be reduced further, greater attention must therefore be paid to the distribution of unpaid work and the role of traditional gender stereotype.

Literature

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. American economic journal: applied economics, 2(3), 228-55.

Cullen, Z. B., & Perez-Truglia, R. (2019). The old boys’ club: Schmoozing and the gender gap. NBER Working Paper 26530.

Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. American Economic Review, 104(4), 1091-1119.

Head-König, A. (2015). Women’s gainful employment. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), version of 5 March 2015, translated from French. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/013908/2015-03-05/call_made, consulted on 8 December 2021.

Kopp, D. (2021): Men seeking part-time jobs are disadvantaged. KOF Bulletin 154.

Petrongolo, B., & Ronchi, M. (2020). Gender gaps and the structure of local labour markets. Labour Economics, 64, 101819.

A recording of the event entitled 'KOF Beyond the Borders: 50 years of women’s suffrage in Switzerland. How far have we come with equality?' is available here.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland