“Inflation will come down again”

- Inflation

- Monetary Policy

- KOF Bulletin

KOF economist Alexander Rathke talks about rising prices in the United States and Europe, the special case of Switzerland and the challenges of monetary policy over the coming years.

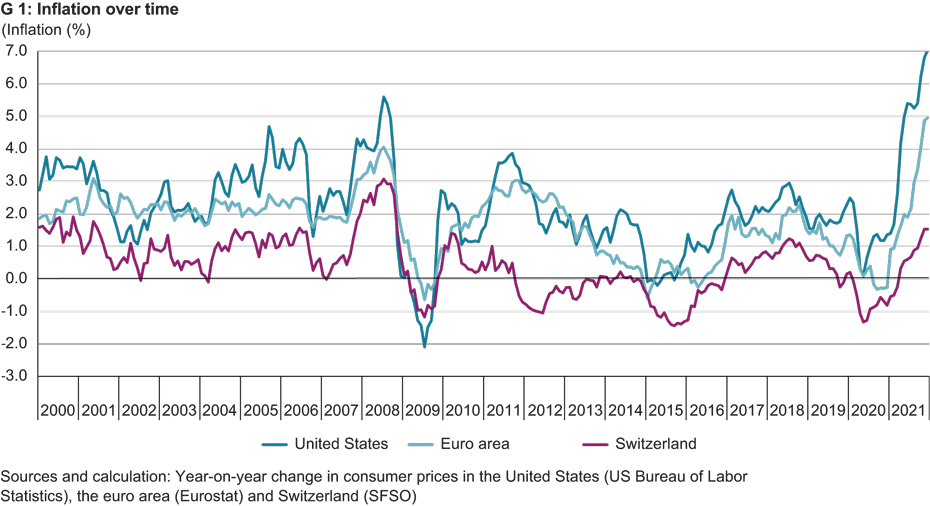

We are currently observing very high inflation rates, especially in the United States, but also in the euro area (see chart G 1). Is this effect permanent or only temporary?

There are currently several factors in almost all currency areas – induced by the coronavirus pandemic – that are pushing inflation up. Once these factors weaken and disappear over the course of this year, inflation should also fall again, although the big question then is what level it will settle at.

What factors are driving inflation?

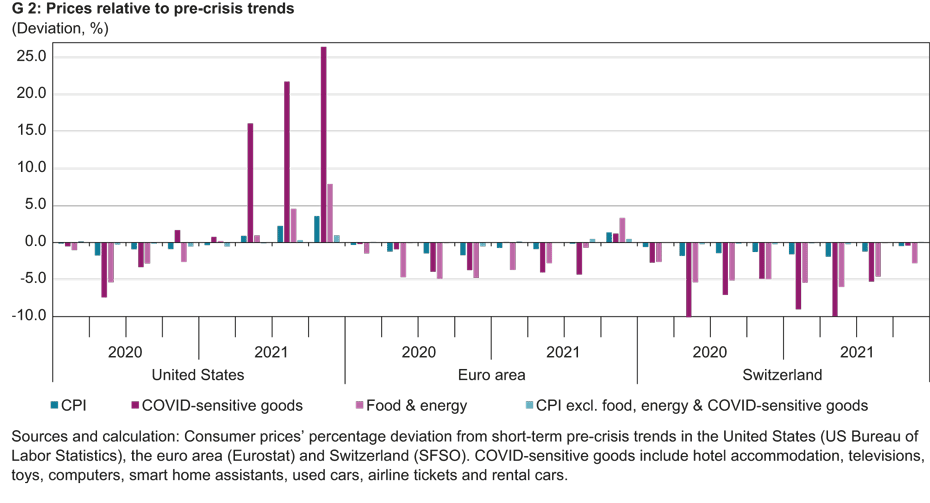

An important part of the explanation is that prices that came under pressure in 2020 owing to the pandemic have recovered. One example is energy prices. These play a bigger role in the US and the euro area than in Switzerland. In Switzerland, energy prices have simply returned to normal and reached pre-crisis levels (see chart G 2). In the United States and the euro area, they are higher than they were before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. This is partly politically desirable for environmental reasons. Secondly, goods in which there are currently supply bottlenecks are driving inflation. These include semiconductors and computer chips as well as cars – both new and used - and rental cars. This increase is being driven by a shortage of supply that cannot keep pace with the occasionally high demand during the recovery. As soon as supply expands again, or demand declines, the prices of these goods should also return to normal.

And what suggests that inflation might remain permanently high after all?

Sustained high inflation always requires sustained high wage growth because a large proportion of our consumption is services, and these in turn depend on wages. This can lead to a wage-price spiral, although it doesn’t look as though that is the case in Switzerland at the moment.

Why is inflation a problem at all? Can’t you just ride it out and wait until it goes down again?

If inflation is higher than wage increases, consumers lose purchasing power. In extreme cases this can cause social unrest. Moreover, if inflation is highly volatile, this makes it difficult for economic actors to plan – when signing loan agreements, for example – because you always have to include a safety margin to compensate for inflation. Situations in which people do not have to worry about inflation are easier to manage.

Why is inflation so low in Switzerland?

Traditionally, inflation in Switzerland is at least one per cent lower than in the euro area. This is partly due to the strong Swiss franc, which makes it cheaper to import foreign goods. In addition, the inflation target set by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) is below the inflation target used by the European Central Bank (ECB), so monetary policy is another factor. Inflation in Switzerland is also lower because interest rates are lower here.

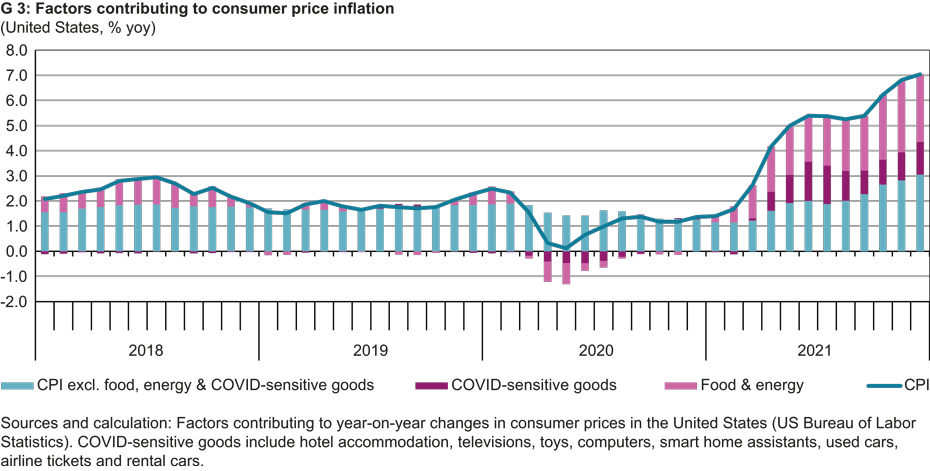

And why is inflation so high in the US at the moment?

Wages and prices in the United States are much more cyclical than they are here. Food prices have also risen more sharply there (see chart G 3). The US Federal Reserve (Fed) adopted a new strategy in 2020 under which it temporarily allows inflation to be above its 2 per cent target. This means that slightly higher inflation than in the past may even be desirable. On the other hand, inflation is now well above target and the Fed has therefore changed course and announced interest-rate hikes for later this year.

What communication mistakes should central banks avoid when preparing such a change of course?

The more a change of course comes as a surprise, the stronger the markets’ reaction will be. One should therefore prepare the markets gently and gradually for such decisions. On the day of an interest-rate hike there is usually hardly any market reaction because it is already priced in.

Central banks are currently buying government bonds on a massive scale (known as ‘quantitative easing’ in the jargon) and, at the same time, are keeping interest rates low. Is there any algorithm derived from economic theory according to which you first have to stop buying government bonds before raising interest rates?

In practice, central banks first end their net bond purchases before raising interest rates, but there is no hard and fast rule here. We have never been in such an exceptional situation before. Inflation over the past decade or so has often been below the targets set by central banks. Now it is suddenly above them. There is no silver bullet here.

We often read that the ECB is trapped in its policy of cheap money because interest-rate hikes would drive highly indebted countries like Italy into bankruptcy. Is there any truth in this theory?

This is only true to a certain extent. If the ECB itself triggers a debt crisis, this runs counter to its goal of ensuring financial stability and may also make it more difficult to achieve the inflation target. But this does not mean that it has no room for manoeuvre at all. Communication in the event of a change of course is very important to ensure that there are no distortions in financial markets or sharply rising interest rates in bond markets.

Finally, let’s gaze into the crystal ball: when will interest rates rise in the euro area and Switzerland?

At KOF we believe that the ECB will not raise interest rates this year because it will first exit from its government bond purchasing programme. And the SNB will also stick to its expansionary monetary policy until the ECB raises interest rates. However, the SNB has already allowed the Swiss franc to appreciate and has thus already taken steps to counteract rising inflation. In principle, it would be good from a macroeconomic perspective if there were to be positive interest rates again at some point – if only to give central banks more leeway to cut interest rates in the event of a crisis or to raise them if there were signs of overheating.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland