Investment controls: a global trend with implications for Switzerland

KOF Bulletin

Many European countries have introduced controls on foreign investment in recent years. Up to 60 per cent of foreign investment is now subject to controls. The Swiss federal administration is working on the consultation draft for these new investment restrictions.

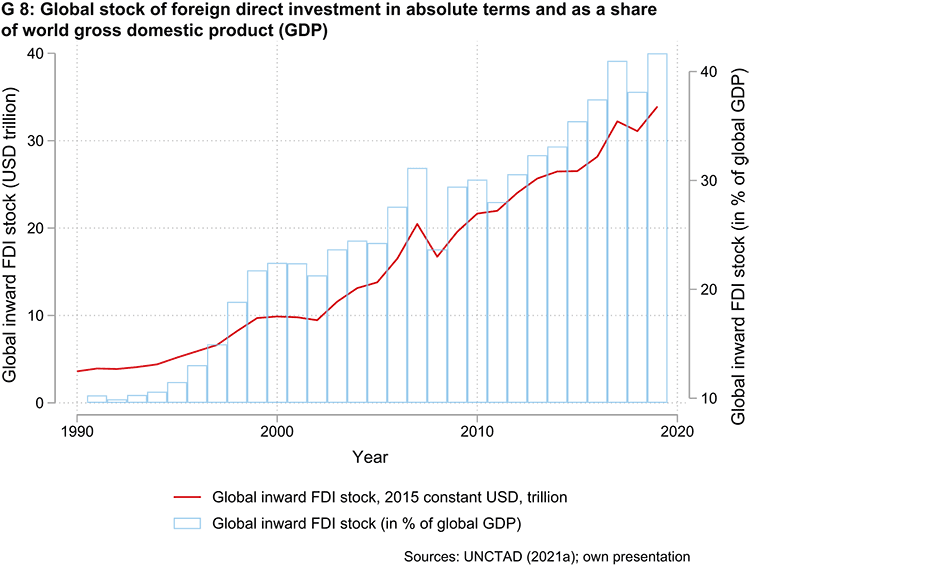

Worldwide foreign direct investment has, for the most part, grown steadily and significantly over the past few decades (see chart G 8). Over this period, attractive terms and conditions for investors have been discussed in connection with investment. Foreign investment brings capital and knowledge to a country, which adds value and helps to preserve and create jobs. For some years now, however, investment has also increasingly been viewed from the perspective of public order and national security because investment brings about a change in the ownership of domestic companies. This gives investors access to information and technology that may be sensitive or relevant to security. Risks such as espionage and sabotage that can accompany foreign investment have, of course, been familiar for some time. In many countries, particularly sensitive areas such as military activities and equipment as well as key infrastructure are therefore either state-owned, closely controlled by the state, require special licences, or access is completely prohibited to foreign investors. This is also the case in Switzerland.

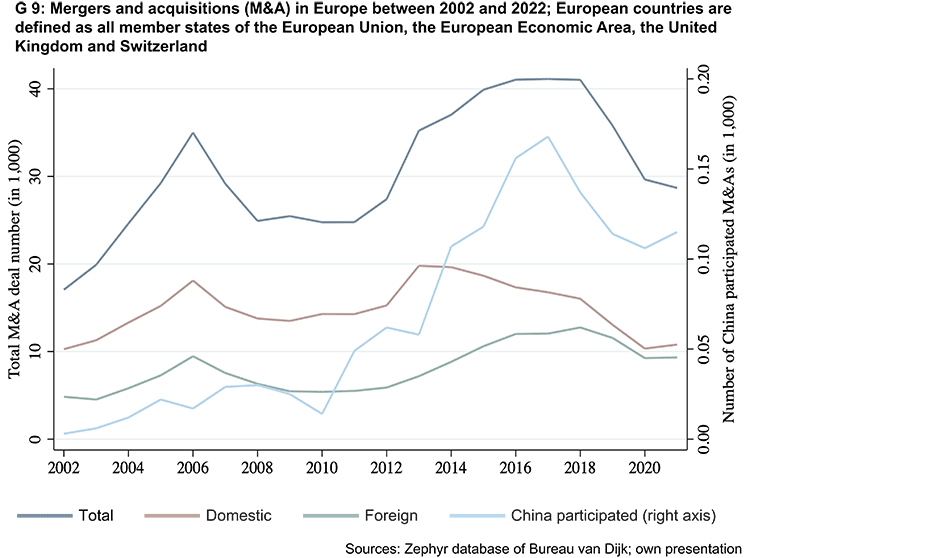

However, the risks involved in foreign investment have changed in the perception of many states. This is due, firstly, to the privatisation and deregulation of certain sectors of sensitive assets that were previously in state ownership and, secondly, to digitalisation, which facilitates access to, and the transfer of, sensitive information and technology. In addition, there was strong growth in Chinese investment in European companies between 2010 and 2017, although this started from a very low level (see chart G 9). KOF’s own calculations, based on data from Bureau van Dijk, show that Chinese investors were involved in only 1.6 per cent of all international mergers and acquisitions (M&A) completed in Europe between 2007 and 2021. Some of these acquisitions have fuelled political and public debate about the one-sided investment opportunities and non-reciprocal knowledge transfer between China and Europe. This discussion, in addition to actual security concerns, may have increased the popularity of investment controls as a policy measure.

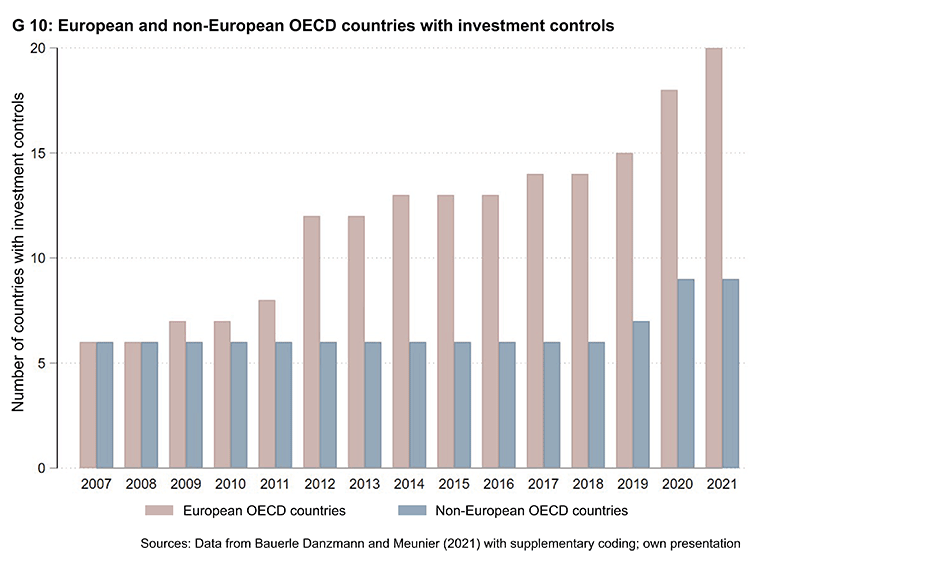

The purpose of controlling foreign direct investment is to avert threats to public order or security. Investment controls can lead to investments being prohibited but, much more often, investments are only allowed under certain conditions such as supply commitments. Investment controls are also likely to discourage certain types of investment. The US has already introduced 1,975 investment controls to address concerns about investment from OPEC countries. Other countries such as Australia and Japan have had some form of investment controls in place for many years. Over the past decade, investment controls have been introduced in many other countries, especially in Europe (see chart G 10). The European Union has also taken action. EU Regulation (2019/452), while not mandating the introduction of national investment controls, sets out a framework for controls and coordinates them with respect to other EU countries. In addition to developed economies, transition countries are becoming increasingly interested in investment controls (OECD, 2022).

Countries with investment controls in place have often amended their laws over the past decade in order to lower thresholds, add critical sectors and establish clear processes and criteria for investment controls. Judicial appeal against investment control decisions is not possible in most countries. In addition, there are (still) no internationally uniform reporting requirements on the number of audited or prohibited takeovers. However, it is known from some countries that the number of audited investments is rising sharply (OECD, 2020). In Germany, for example, 160 takeovers of domestic companies by foreign investors were audited in 2020, with relevant security risks being mitigated by contractual agreements in almost all cases. Only one project was banned. As the current example of German chip manufacturer Siltronic being taken over by Taiwanese chip supplier GlobalWafers shows, deals worth billions can be thwarted by lengthy review procedures that involve international dimensions. The KOF Swiss Economic Institute is currently collecting data on the levels of investment controls in place across countries and over time. This allows us to analyse how such controls have affected the numbers of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and other variables.

The investment controls used by various countries differ in various respects. This can be seen, for example, from the thresholds that are set for audits. Most countries with investment controls in place scrutinise takeovers involving voting shares of between 10 per cent and 25 per cent, while in Japan, since 2019, acquisitions involving voting shares of 1 per cent or more have been examined. The trend is clearly moving towards lower thresholds.

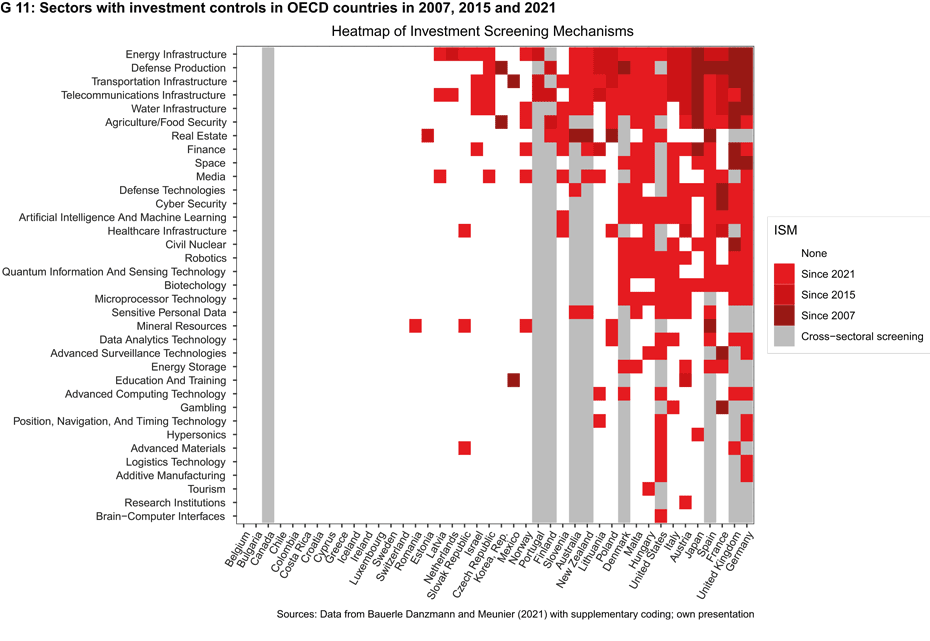

In addition, investment controls are being extended to a growing number of sectors such as artificial intelligence and microprocessor technologies (see chart G 11). The sectoral definitions used are often broad and increasingly include activities involving advanced technologies, partly because these (can) enable security-related applications. During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020, many countries also defined their biotechnology and healthcare infrastructure sectors as security-relevant or they tightened the relevant screening criteria. In many countries, however, such tightening of criteria is only to apply temporarily. Investment controls in selected sectors are primarily justified by the protection of public order. However, it is safe to assume that investment controls are also used to keep key or future-relevant companies and technologies with strategically important knowledge in domestic hands (Eichenauer et al. 2021). In addition to security aspects, certain countries even explicitly examine whether a foreign investment generates a net benefit for the country in which the company is domiciled.

The impact of investment controls on mergers and acquisitions is still unknown

The OECD (2022) estimates that up to 60 per cent of global direct investment is subject to investment controls. Although such controls are intended to prevent corporate mergers and acquisitions as far as possible, very few takeovers are actually prohibited by the authorities. According to the latest figures available (2018, 2019 and 2020), one investment project was banned in each of these years in Australia, Germany and the United States, two in Canada, and none at all in New Zealand (UNCTAD, 2021b: 133). Nevertheless, economic theory suggests that the cost of providing all required documentation to the authorities, the time delays caused by the review process, and the uncertainty about the outcome of the process – which is likely to be considerable in the early years of implementation and after reforms – will deter some foreign investors. These distortionary effects are stronger in the case of investment controls that scrutinise even small absolute or percentage changes in ownership. The effects of the latest investment controls on the numbers of company takeovers or on acquisition prices in Europe have not yet been systematically studied. Older studies from the US show that investment controls can reduce companies’ valuations because there is less competition for their acquisition.

Swiss plans for investment controls

Switzerland is following the international trend and will soon introduce investment controls. Draft investment controls are based on acceptance of the Rieder motion entitled ‘external page Protection of the Swiss economy through investment controls’ (18.3021). The Swiss Federal Council set out the key elements of controls on foreign investment in domestic companies in August 2021, although crucial aspects and definitions will not be available until the consultation draft is submitted at the end of March this year. The government is of the view that the cost-benefit ratio for investment controls is inadequate and that the existing regulatory framework is sufficient (Federal Council 2019). Nevertheless, the Federal Council (2021) lists six hazards or threats, including the failure of a systemically important company without any short-term alternatives available, personal data requiring protection, significant distortions of competition by government or state-related investors, and critical dependencies of the Swiss government on defence components and key security-relevant IT systems. Since, according to the Federal Council’s assessment, threats are likely to emanate primarily from state-related investors, such takeovers should have to be reported and approved in all sectors. It is still unclear in which sectors the Swiss government will be scrutinising private investment. From an international perspective, no strict threshold value is expected to be applied to audits: investments will only be scrutinised if there is a change of control over the domestic company. In such cases, a two-stage examination will be carried out by SECO, with the second stage only being required for in-depth approvals. If the federal authorities recommend a takeover ban, the Federal Council will have the final decision on the ban as this has a political dimension and would hardly be viewed positively in the investor’s country.

In addition, Swiss investment controls should include the possibility of cooperation with other countries as well as mutual exemptions from the respective investment controls. This last point suggests that bilateral and multilateral agreements could be negotiated over the coming years, which would enable countries with comparable value systems and economic models to mutually waive controls on private investment (in certain sectors). Such agreements, which are still speculative, would once again enable investment opportunities in Switzerland’s key partner countries to be more readily available than they have been in recent years.

References:

Bauerle-Danzman, S. and S. Meunier, 2021. “The big screen: Mapping the diffusion of foreign investment screening mechanisms.” Unpublished Research Note.

Federal Council, 2019. “external page Cross-border investments and investment controls”, Report of the Federal Council in fulfilment of Postulates 18.3376 Bischof of 16 March 2018 and 18.3233 Stöckli of 15 March 2018. Bern, Switzerland. 13.02.2019 external page https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/55636.pdf

Federal Council, 2021. “Bundesrat legt die Eckwerte einer Schweizer Investitionskontrolle fest”, media release. Bern, Switzerland. 25.08.2021. external page https://www.admin.ch/gov/de/start/dokumentation/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-84838.html

Eichenauer, V. Z., M. Dorsch and F. Wang, 2021. “Investment Screening Mechanisms: The Trend to Control Inward Foreign Investment”, EconPol Policy Report 34. Munich, Germany: Ifo Institute, University of Munich. URL: external page https://www.econpol.eu/sites/default/files/2021-12/EconPol_PolicyReport34.pdf

Pohl, Joachim and Nicolas Rosselot, 2020. “Acquisition- and ownership-related policies to safeguard essential security interests. Current and emerging trends, observed designs, and policy practice in 62 economies.” Paris, France: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development.

OECD, 2022. Investment policy developments in 62 economies between 16 October 2020 and 15 October 2021. Freedom of Investment Process. URL: external page https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/Investment-policy-monitoring-October-2021-ENG.pdf

UNCTAD, 2021a. “Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock.” Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. URL: external page https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740

UNCTAD, 2021b. “World Investment Report.” Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Contact