“The war in Ukraine is a massive economic risk”

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

KOF economist Heiner Mikosch, Head of the International Business Cycle Section, talks about the economic dangers for Europe and Switzerland posed by Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

We have just come through the coronavirus pandemic, at least in theory. Might the war in Ukraine turn out to be the next economic risk?

The war in Ukraine is a massive economic risk. If this war and the sanctions spread and then raw-material exports from Russia to Europe are cut off, this will trigger a severe recession in Europe. Although this will not be comparable with the coronavirus pandemic, it could be very serious.

During the COVID-19 pandemic we have learned to think in scenarios, for example in terms of possible variants of the virus. From an economic forecaster’s point of view, is the world – given the current political and military risks – comparable with the world of the coronavirus pandemic?

As in the COVID-19 pandemic, we are actually in a classic scenario situation right now. Because what matters most now is the political actors. However, this political chess game is almost more difficult to model than the spread of a virus, which spreads according to certain laws.

What does KOF’s latest economic scenario look like?

Our latest positive scenario is that the war will be over in no more than three months, either through a military victory by the Russians or through a face-saving withdrawal by the Russians. As far as the short-term forecast is concerned, both variants amount to roughly the same thing from a European perspective. Given the strong asymmetry of forces between the Russian and Ukrainian militaries, it is quite possible that acute hostilities will not last very long. If this scenario occurs, the war’s negative impact on the global economy could be mostly limited to the second quarter of this year, even if the current sanctions against Russia remain in force thereafter. However, the structural shifts in the global economy are likely to be further intensified by the war.

And what assumptions does the negative scenario involve?

In our negative scenario the conflict between Russia and the West intensifies even more and sanctions are extended to cover the entire commodity trade. In this event, some of Europe’s energy supplies would collapse. Germany – about 55 per cent of whose gas imports come from Russia (oil: 35 per cent, coal: 50 per cent) – is heavily exposed here, but so, for example, are Italy and, especially, the eastern European countries. Although their reserves are still sufficient to last for a few months, energy rationing would soon occur in Europe if this negative scenario were to materialise. Overall economic output in Europe would suffer greatly, even though rationing would probably be targeted at non-core sectors of the economy. In this negative scenario there would be an economic slump which, although not as severe as that during the coronavirus pandemic, would nevertheless be massive.

Switzerland has come through the coronavirus pandemic relatively well. Is there hope that it will also be able to cope well with the current crisis?

As an export-led economy with a strong European network, Switzerland is affected by the negative international economic impact of the war. However, it is not as dependent on Russian energy exports as some other countries in Europe. Another exceptional factor is that about 40 per cent of Switzerland’s exports are chemical and pharmaceutical products. These sectors are less sensitive to economic cycles than, for example, manufacturing is. This has protected Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic and should continue to benefit the country during the current crisis. However, the considerable importance of the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors can also become a cluster risk in other cases. It should also be noted that about 80 per cent of Russia’s transit trade in commodities is handled by companies in Switzerland. Trade in Russian commodities accounts for between 15 and 20 per cent of total transit trade in Switzerland, and this in turn represents about 5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). I therefore believe that any disruption of Russian energy exports to Europe owing to the transit trade then being put on hold will have a highly negative impact on value added in Switzerland. Even if there is no disruption of exports, there is likely to be an adverse impact because the current sanctions already seem to be restricting the activities of some banks. However, the value added by the transit trade generally fluctuates very sharply and the sector has few jobs.

How much is Russia harming itself economically as a result of the war?

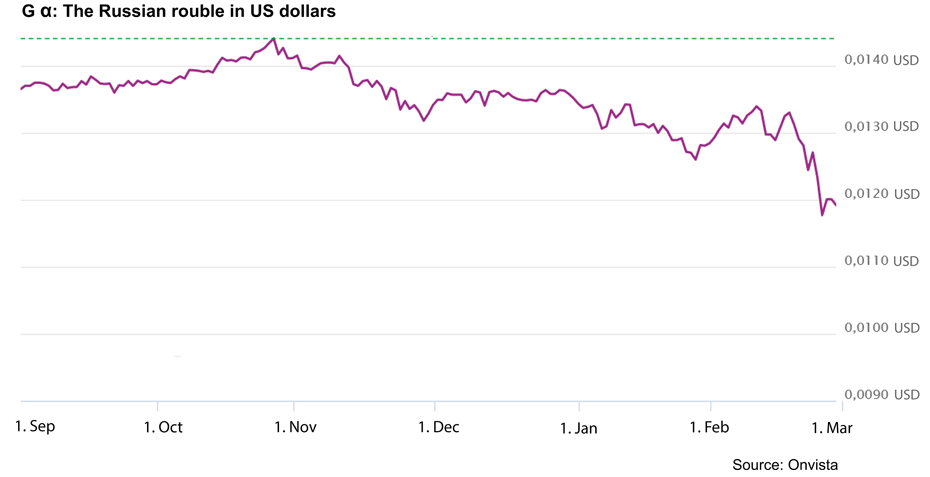

The Russian economy is likely to suffer enormously from the sanctions imposed because of the war. The rouble and Russia’s gross domestic product both collapsed when Crimea was annexed back in 2014, although this also had to do with the collapse in commodity prices at the time. The COVID-19 pandemic was then the next massive shock. Russia had actually been trying to protect itself against rouble shocks by expanding its foreign-currency reserves since 2014. However, the freezing of the Russian central bank’s foreign-exchange reserves has massively limited its ability to halt the devaluation of the rouble by buying its own currency. This is one reason why the rouble has fallen to a new low this week (see chart α).

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has spoken of an “epochal shift”. Will the war affect globalisation and international financial and trade flows?

I think this epochal shift has already happened and German politics is now catching up. In China and the United States we have two dominant players fighting for political and economic supremacy in different regions of the world. I reckon that the sanctions imposed in the wake of the war in Ukraine will limit Russia’s ability to perform an independent role in the international power play over the medium term. Whether the current conflict will persuade the EU to increase its ability to take independent action in the longer term, or whether European countries will align themselves even more closely with the United States, is difficult to assess. The formation of political blocs could lead to a deepening of financial and trade flows regionally or within geopolitical blocs rather than globally. A rational response to the growing conflict risks would be to increase diversification of international trade chains.

Inflation was already high in almost all industrialised countries before the war in Ukraine. Will it rise even more now because of the war?

Until the outbreak of the war, the supply shortages that had recently caused a surge in inflation were no longer as severe as they had been at the beginning of the year. But just when this shock seemed to be gradually being digested, then came the next price shock caused by rising energy prices. Consumers saved lots of money during the coronavirus pandemic and are now looking to consume in large quantities again. These are favourable conditions for companies to raise their prices. In addition, the situation in the labour market is encouraging, which should ensure that wages rise in the medium term. This situation poses the risk that these price surges will eat into core inflation by means of a wage-price spiral and lead to higher inflation than desired in the medium term. What matters most now is the response by central banks.

But aren’t central banks faced with the dilemma that, on the one hand, they need to raise interest rates to curb inflation but, on the other hand, they cannot raise rates because the world economy is weakening owing to the war in Ukraine?

Absolutely. Central banks are in a particularly difficult situation at the moment. I believe that the US Federal Reserve will nevertheless not abandon its current plans to tighten policy. Core inflation in the US is simply too high for that at the moment. Our assessment for the European Central Bank is more difficult. In our positive scenario, there is, in my view, no reason for the ECB to refrain from raising interest rates in the second half of the year. If the war and sanctions intensify as assumed in our negative scenario, however, this is likely to trigger a recession in Europe and even stronger price spikes at the same time. Then even the central banks will have run out of options. At least they can still intervene swiftly to prevent a banking crisis.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland