Obwalden’s low-tax strategy under the microscope

Countries, as well as constituent states within countries, compete for high-income taxpayers. Tax competition and attempts to keep aggressive tax practices in check have increased in recent decades. However, even if low income-tax rates attract top earners, this does not necessarily mean that simple tax cuts alone will pay off. Typically, only a combination of measures leads to success.

While there is ample evidence to suggest that tax cuts are an effective way of attracting top earners, what does a canton, region or country gain from such tax policies?

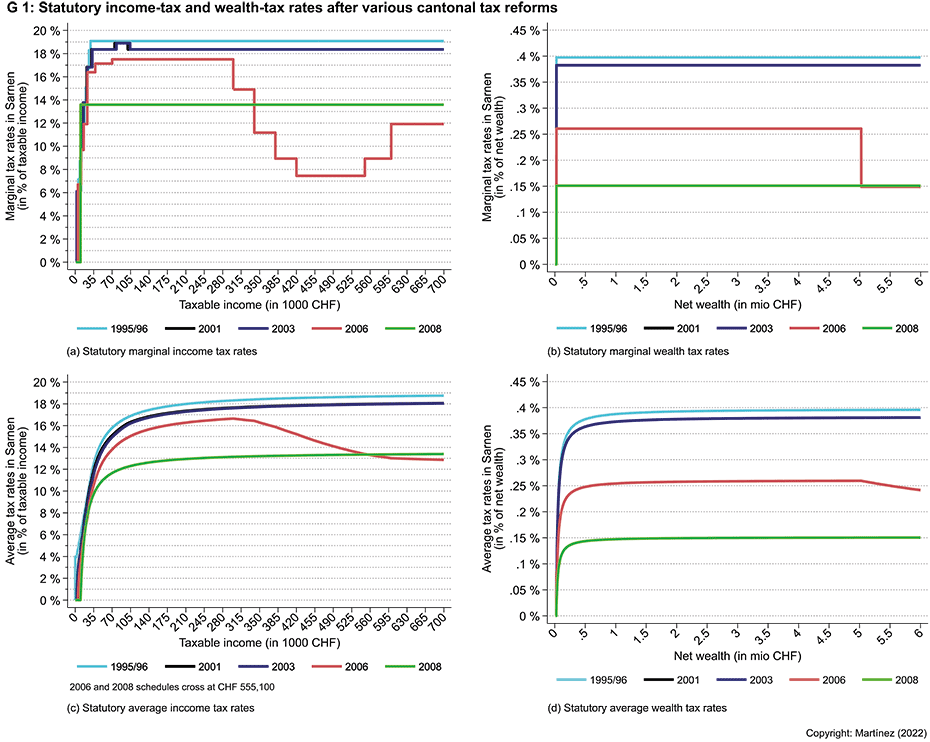

A study by KOF economist Isabel Martínez, which was recently published in the Journal of Urban Economics (Martínez, 2022), examines the tax cuts introduced by the canton of Obwalden in Central Switzerland. The explicit aim of this tax reform, which was announced in 2005, was to attract high-income taxpayers. To this end, the canton introduced a regressive income-tax and wealth-tax scale in 2006. This reduced the marginal tax rates on taxable incomes of more than CHF 300,000 and on assets above CHF 5 million. The introduction of this regressive regime meant that the average cantonal income-tax rate for a single taxpayer with a taxable income of CHF 500,000 fell from 17.9 per cent to 14 per cent after the reform. The average tax rate for an otherwise identical taxpayer with a taxable income of CHF 300,000, on the other hand, only fell from 17.6 per cent to 16.6 per cent. Chart G 1 shows the marginal and average tax rates (including direct federal tax) before and after the reform. Given its regressive nature, this reform was rejected by Switzerland’s Federal Supreme Court in 2007. Consequently, the canton introduced a flat-rate tax in 2008, which further reduced the average tax burden (even though marginal tax rates on high incomes increased again slightly).

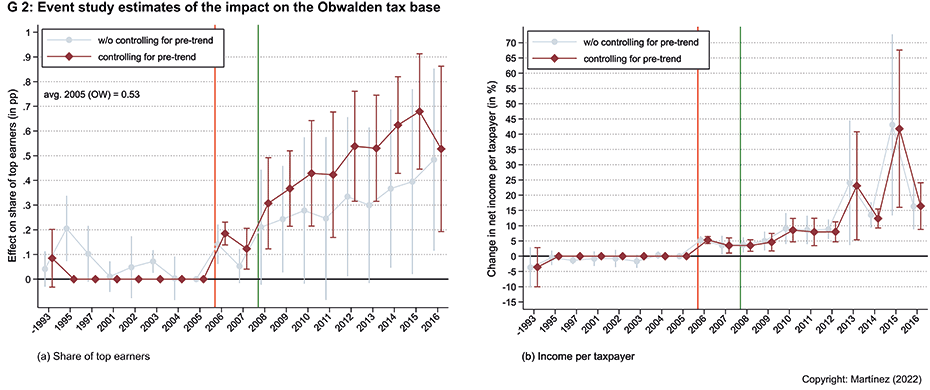

Using data from the direct federal tax, the study first analyses (i) the percentage of taxpayers with taxable incomes of more than CHF 300 000, and (ii) the net income per taxpayer in Obwalden compared with other cantons as part of a difference-in-differences analysis. The results of the corresponding event studies in Chart G 2 show that the reform had the intended effect: by 2016, the proportion of high-income taxpayers in Obwalden had risen by 0.53 percentage points compared with other cantons. This represents an increase of 100 per cent compared with the original proportion of top earners in Obwalden. The net income per taxpayer grew by 17 per cent.

Are these changes now large or small? To answer this question, tax elasticities are calculated in finance. These compare the size of the behavioural change in relation to the size of the tax change. This means that the behavioural changes observed as a result of different reforms and tax changes can be compared across various studies. Typically, the net average tax rate is used for this purpose, i.e. 1 minus the average tax rate. This rate indicates what percentage of a taxpayer’s income remains after taxes have been paid.

By using individual tax data from the canton of Obwalden, it was possible to examine the annual inflows and the annual stock of top earners in the canton. This analysis shows that the elasticity of immigration was extremely high: a 1 per cent rise in the average net tax rate increased the inflow of top earners by an estimated 7.2 per cent in the first five years after the reform. These inflows occurred immediately after the reform and levelled off slightly over time. The more precisely calculated elasticity of the stock of high-income taxpayers living in the canton (which also takes account of residents who stayed but might otherwise have moved elsewhere) is within the range of 1.5 to 2, so the reform was a success in this respect.

These elasticities turn out to be relatively high (see Kleven et al., 2019, for a review) but need to be understood in an institutional context.

- Elasticities are greater when there are no restrictions on occupation, income source, nationality or origin to benefit from lower taxes. In this respect, Switzerland comes close to Tiebout’s (1956) model world, where people vote with their feet to optimise their taxes (taking into account the public goods offered by a canton or municipality.

- Switzerland is a small country. The distances involved and, consequently, the costs of relocation are modest, which increases the willingness to move.

- These controversial tax changes were extensive and conspicuous. When such reforms are introduced, people are more likely to consider moving for tax reasons than in the event of a mini-reform that few are aware of

- The canton of Obwalden started from a situation where very few top earners moved to or lived in the canton. The relative changes were very large for such a small canton.

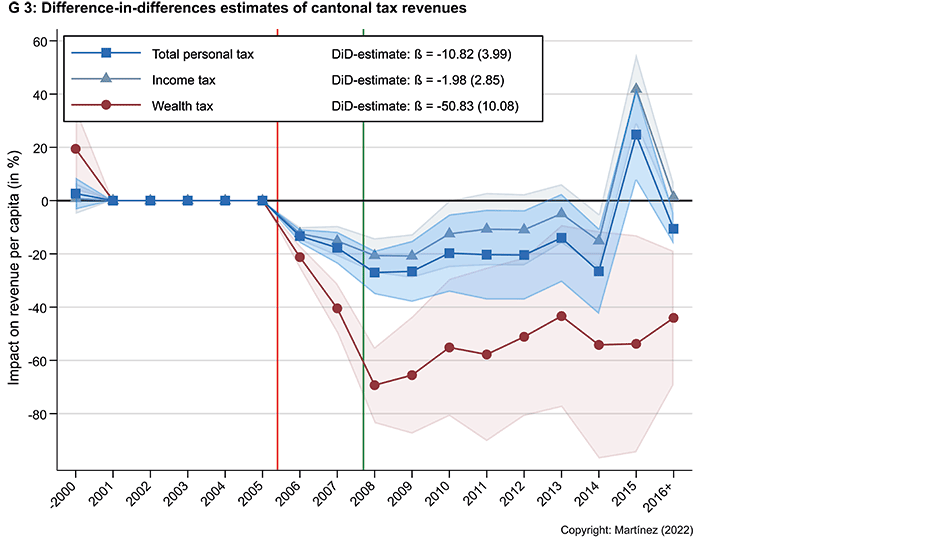

But how much has Obwalden really gained, apart from the fact that more high-income earners live in the canton? Event studies comparing cantonal tax revenues in Obwalden with revenues in other cantons (Chart G 3) show that the reform has not increased per-capita revenues from taxes on individuals. Although total tax revenues in Obwalden have grown over time, revenues from taxes on individuals in other cantons have risen even more over the same period thanks to strong economic growth. The study thus also raises the question of which benchmark to use to measure the success of such tax reforms.

The study does not take account of any further tax losses. Because Obwalden has attracted so much of the tax base, income from the New Fiscal Equalisation (NFA) has fallen. Obwalden has been a net contributor since 2019. In 2006, Obwalden cut corporate taxes to what at the time was Switzerland’s lowest rate of 6.6 per cent. A rough calculation conducted by Brülhart (2012) revealed that this tax cut led to even higher losses.

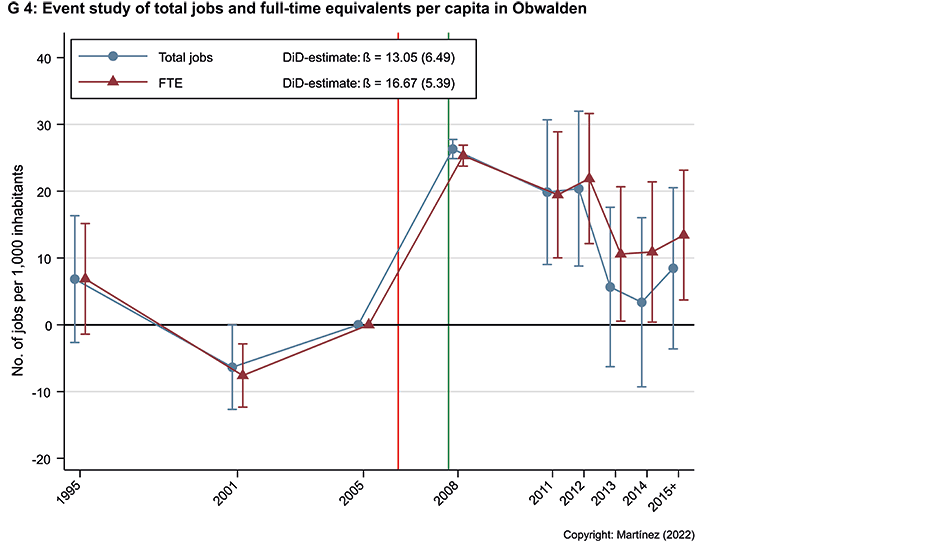

Nevertheless, the canton regards its tax strategy as a success. At any rate, its image transformation from being a high-tax jurisdiction in Central Switzerland to being a minor tax haven has been successful. In fact, the number of jobs in terms of full-time equivalents (FTEs) has also risen. Difference-in-differences estimates imply a 2.3 per cent increase in the number of jobs per capita and 4 per cent growth in the number of FTE jobs per capita as a result of the reform (see also event studies in Chart G 4). However, these increases are probably not solely due to this income tax reform but also to the massive, costly reduction in the profit tax rate. Unfortunately, the data available does not enable us to statistically cleanly separate out the effects that the two reforms have on employment.

Attracting highly skilled top earners can have positive spill-over effects on the local economy. However, this is usually only the case if tax policies are targeted and combined with industrial policy measures (see, for example, Moretti and Wilson, 2017, for the US). Tax cuts for individuals alone tend to incur revenue losses despite relocations, especially if we compare the level of revenues over time with a situation in which taxes are not cut. Agrawal and Foremny (2019) also come to this conclusion in their study on regional tax cuts in Spain.

References

Agrawal, D. R., Foremny, D., (2019): ‘Relocation of the Rich: Migration in Response to Top Tax Rate Changes from Spanish Reforms.’ Review of Economics and Statistics 101(2): 214-232.

Brülhart, M. (2012): ‘Success story Obwalden?’, Batz.ch, 22.02.2012 external page https://batz.ch/2012/02/erfolgsgeschichte-obwalden/

Kleven, H., Landais, C., Muñoz, M., and Stantcheva, S. (2019): ‘Taxation and migration: evidence and policy implications.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(2): 119-142.

Martínez, I. Z. (2022): ‘Mobility responses to the establishment of a residential tax haven: Evidence from Switzerland.’, Journal of Urban Economics, 129(103441).

Moretti, E., and Wilson, D. (2017): ‘The Effect of State Taxes on the Geographical Location of Top Earners: Evidence from Star Scientists.’ American Economic Review, 107(7): 1858-1903.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956): ‘A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures.’ Journal of Political Economy, 64(5): 416-424.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland