How computerisation is driving the immigration of highly skilled workers

There is a renewed shortage of skilled labour in Switzerland. A recent study published in the Journal of Population Economics shows how computerisation is driving the Swiss economy’s demand for highly skilled workers. This trend is thus having a significant impact on what sort of people are immigrating to Switzerland.

According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, 38 per cent of companies stated in the first quarter of 2022 that they had difficulty recruiting qualified workers or could not find them at all – an all-time high. Unemployment is extraordinarily low and many jobs cannot be filled. Given the shortage of skilled workers available to Swiss firms, immigration is on the rise again. While net immigration in 2020 was at its lowest level for 15 years at 47,300 people owing to the pandemic, it rose significantly to 62,500 in 2021. Such immigration can mitigate labour shortages. Switzerland’s State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) reports that the number of people employed in information and communication technology occupations rose by 60 per cent between 2010 and 2021. Almost half of this growth was accounted for by foreign workers. Overall, nearly one-third of IT professionals thus come from abroad. The proportion of foreign workers across the economy as a whole is just over 26 per cent. Immigration thus makes an important contribution to meeting the demand for skilled workers (SECO, 2022)

Boom in immigration of highly skilled workers

The immigration of highly qualified individuals has also been booming internationally. Across the OECD countries as a whole, the proportion of migrants with tertiary education rose by almost 130 per cent between 1990 and 2010. However, highly skilled immigrants are not evenly distributed among the destination countries. The most attractive countries for immigrants are the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. Around 70 per cent of all highly skilled migrants choose these destination countries. But Switzerland is also attractive, with its share of highly skilled newcomers increasing from 21 per cent in 1990 to 44 per cent in 2010 and to as much as 61 per cent in 2020. Over this period the proportion of highly skilled natives also grew, but was ‘only’ 36 per cent in 2020. In some regions – such as Zurich, Zug and Basel – the share of new immigrants with tertiary education was as high as 75 per cent, while in regions around Aarau and Solothurn it was roughly 45 per cent.

What factors are driving this boom in the immigration of skilled workers and determine which destinations they choose? Can and should politicians seek to control the immigration of talent? Scientific studies suggest that highly skilled immigrants often make a positive contribution to firms’ growth and innovation (Beerli, Ruffner, Siegenthaler, Peri, 2021), stimulate trade (Ariu, 2022) and improve the public finances (Dustmann, Frattini, 2014), usually without having significant displacement effects on the labour market (Beerli, Ruffner, Siegenthaler, Peri, 2021). No wonder, then, that the immigration of highly skilled workers is welcomed across a broad political spectrum.

A study by KOF economists Andreas Beerli, Ronald Indergand and Johannes Kunz entitled external page ‘The supply of foreign talent: how skill-biased technology drives the location choice and skills of new immigrants’ – published in the Journal of Population Economics – shows that structural change in the labour market in the wake of computerisation is driving the boom in highly qualified immigrants. The link here is obvious, especially since various studies show that countries with greater wage inequality between high- and low-skilled workers typically experience stronger immigration of high-skilled workers (Grogger, Hanson, 2011). The premium available for higher levels of education in the labour markets of such countries is larger, which is why immigration is particularly worthwhile for the highly skilled. At the same time, various international studies have shown that computerisation has sharply increased the education premium available since the 1980s and has created new jobs for the highly skilled. So to what extent are the two phenomena linked?

Computerisation creates labour market opportunities that vary according to education level

The study first examines which regions in Switzerland are affected by computerisation and to what extent. Existing studies show that computerisation accelerated strongly, especially from 1980 onwards, when microprocessors became much cheaper and companies began to use more computers and machines for work processes that could be automated (Autor & Dorn, 2013). Assembly-line workers were replaced by robotic arms and office assistants were displaced by software. Machines were thus mainly used for certain repetitive processes – so-called routine tasks. Regions that had had a higher proportion of such routine tasks owing to their industrial structure before 1980 were more exposed to this automation.

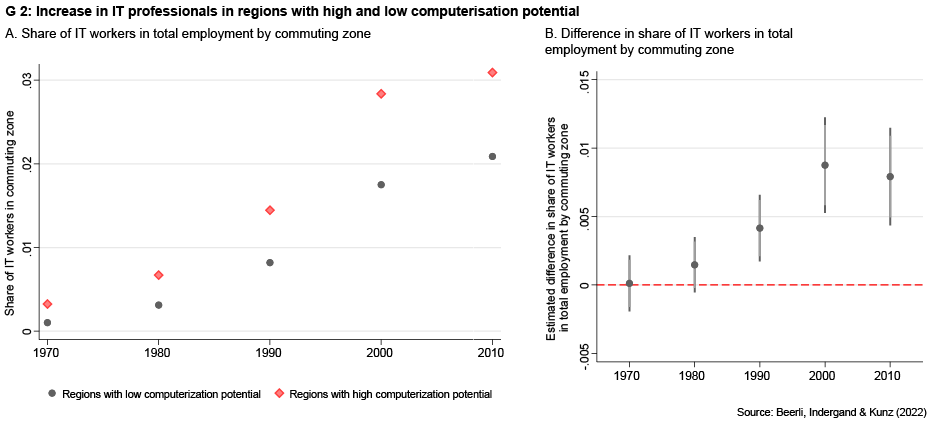

Using the 1970 census, this exposure can be measured as the proportion of workers in occupations with a high degree of routine tasks. Chart G 2 divides Switzerland’s 106 commuter regions into two groups: those with a high share of routine jobs in 1970 and those with a low share. Since investment in computers and robots cannot be measured directly for this period, the chart instead shows the proportion of workers in IT occupations for each decade from 1970 to 2010 as an indicator of computerisation. In 1970 the share of employees in IT occupations was virtually the same in both regions. As the price of computers started falling from 1980 onwards, however, this proportion grew much more in those regions that had previously had a large proportion of routine tasks that could be ‘automated’.

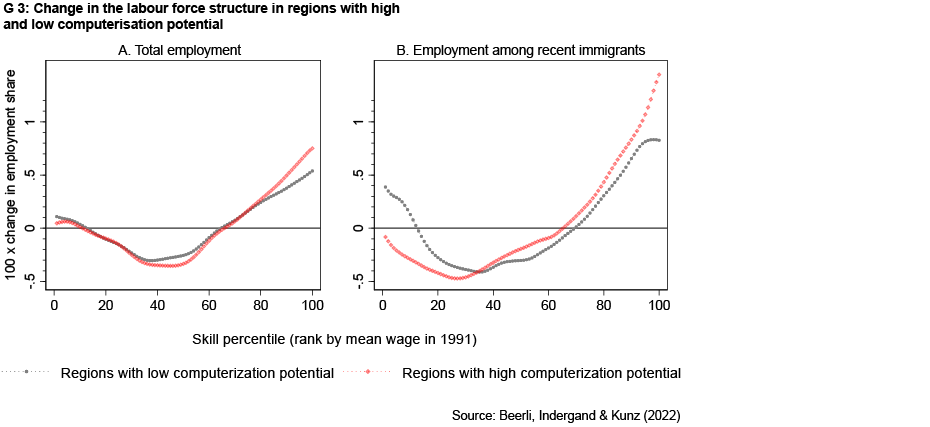

The greater use of computers and machines affected wages and job opportunities in local labour markets. The (wage) premium for tertiary-educated people in more exposed regions rose much faster than it did in less exposed regions. The structure of the labour force changed accordingly. The left-hand part of Chart G 3 shows the change (from 1990 to 2010) in the proportion of all workers in different occupational groups, ranked by their wage percentile (from 0 to 100), again for both groups of regions. Positive values on the Y-axis show an increase in the employment share of an occupational group, while negative ones show a decrease. Employment in well-paid occupations (75th percentile and above) grew sharply. Typically, these are highly skilled jobs, e.g. in managerial, graduate or technical occupations. This increase is once again significantly greater in regions with higher computerisation potential. In occupations between the 20th and 60th percentiles, on the other hand, the share of employment decreased significantly. These are typically jobs for workers with intermediate levels of education (such as an apprenticeship diploma or the Matura school-leaving certificate), who are employed as office workers or in industrial and artisan occupations.

The use of computers has thus improved both wages and job opportunities for high-skilled workers compared with people with intermediate levels of education. Various studies confirm similar trends in other countries as well, e.g. in the US (Autor and Dorn, 2013), the UK (Goos and Manning, 2007) and Germany (Spitz-Oener, 2006)

Immigration follows job opportunities in the labour market

The right-hand part of Chart G 3 shows that these trends are even more pronounced among recent immigrants. Whereas in 1990 the typical recently immigrated foreign worker was still employed in low-paid manual or service occupations, this picture had fundamentally changed by 2010. In that year, the typical recent immigrant worked in well-paid graduate, managerial or technical occupations. Immigrants thus followed the changing opportunities available in the labour market. This was reflected in their level of education.

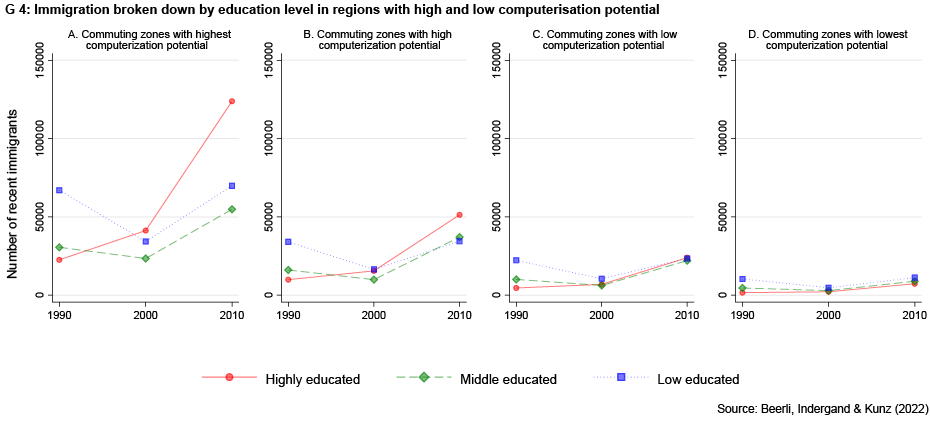

Chart G 4 divides the Swiss commuter regions into four equally sized groups according to their computerisation potential from left (high potential) to right (low potential). The Y-axis shows the number of recent immigrants for each of three educational groups: primary education, secondary education and tertiary education. The chart shows a clear increase in recent immigration. Whereas in 1990 about 230,000 people had a short-term settlement permit, in 2010 this figure was around 500,000. Highly qualified immigrants were the smallest group across all regions in 1990. In the following two decades, on the other hand, the highly skilled were the largest group of immigrants in all but those regions with the smallest computerisation potential.

Conversely, the number of low-skilled and medium-skilled immigrants decreased significantly in the 1990s and then increased in the 2000s, albeit less sharply. These trends among educational groups are much more pronounced in regions with greater computerisation potential, which also experienced a real boom in the immigration of highly qualified people in the 2000s. More detailed regression analysis confirmed this correlation between computerisation potential and stronger immigration of highly skilled workers. This analysis also showed that it was primarily the service sector that employed the largest share of new foreign talent.

The impact of the free movement of individuals

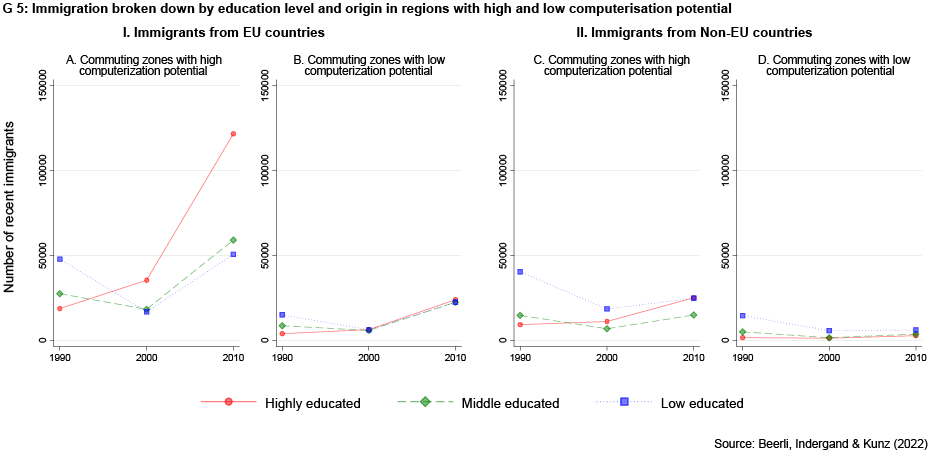

To what extent has the free movement of people from 2002 onwards helped or hindered these long-term trends? One fear in the run-up to this date was that the abolition of all immigration restrictions on Europeans could fuel large-scale immigration of low-skilled workers. Chart G 5 shows that this did not prove to be the case. The left-hand part of the chart shows immigration from EU countries – again for regions with high and low computerisation potential. The right-hand part of the chart shows immigration from non-EU countries – also for both groups of regions.

This chart reflects the same trends that we have already seen for all immigrants in Chart G 4. The share of highly skilled workers has risen sharply for both EU and non-EU immigrants. We can also see that immigration from EU countries between 2000 and 2010 was much stronger than immigration from non-EU countries during the same decade.

The chart also shows a very clear increase in immigration of highly skilled individuals from EU countries to regions with high computerisation potential. More precise empirical evaluations confirm the impressions from the chart. The free movement of individuals has increased the immigration of male and female migrants throughout Switzerland by roughly the same amount in all education groups. This means that the educational composition of migrants from the EU has more or less mirrored that of migrants from third countries. However, we can see that the free movement of individuals has enabled regions with especially strong demand for highly qualified people to recruit more such immigrants from EU countries.

What we can learn from this

The study shows that immigration to Switzerland is responding strongly to the structural changes in labour markets in the wake of computerisation. Computerisation has improved not only wages but also the availability of jobs for the highly skilled. These changing opportunities in the labour market have determined which groups of migrants were particularly keen to relocate to Switzerland and where they settled. The free movement of individuals has accelerated this trend rather than stopping it.

The study entitled ‘The supply of foreign talent: how skill-biased technology drives the location choice and skills of new immigrants’ published in the Journal of Population Economics is available external page here.

Literature

Ariu, A. (2022): Foreign Workers, Product Quality, and Trade: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. CEPR Discussion Paper 14859.

Autor D.H., D. Dorn (2013): The growth of low skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review 5(103):1553–1597.

Beerli A., J. Ruffner, M. Siegenthaler, G. Peri (2021): The abolition of immigration restrictions and the performance of firms and workers: evidence from Switzerland. American Economic Review 111(3):976–1012.

Dustmann C., J. Ludsteck, U. Schönberg (2009): Revisiting the German wage structure. Quarterly Journal of Economics

124(2):843–881.

Dustmann C., T. Frattini (2014): The fiscal effects of immigration to the UK. Economic Journal 124(580):593–643.

Goos M., A. Manning (2007): Lousy and lovely jobs: the rising polarization of work in Britain. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1):118–133.

Goos M., A. Manning, A. Salomons (2014): Explaining job polarization: routine-biased technological change and offshoring. American Economic Review 104(8):2509–2526.

Grogger J., G. H. Hanson (2011): Income maximization and the selection and sorting of international

migrants. Journal Development Economics 95(1):42–57.

SECO Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft (2022): 18. Bericht des Observatoriums zum Freizügigkeitsabkommen Schweiz EU. Auswirkungen der Personenfreizügigkeit auf Arbeitsmarkt und Sozialleistungen. Bern.

Spitz-Oener A. (2006): Technical change, job tasks, and rising educational demands: looking outside the wage structure. Journal of Labor Economics 24(2):235–270.

Contact

KOF FB KOF Lab

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland