A politician’s perfect storm: when disaster relief is politically biased

Politicians often act in a biased manner when allocating public funds. To date, however, it has only been possible to quantify strategic political bias on average. A recent analysis of government disaster relief allocation in response to hurricanes in the United States now shows that the extent of political favouritism varies greatly according to the decision-making situation. The issue is most pronounced for medium intensity storm events.

Tropical cyclones such as hurricanes are among the most destructive natural disasters in the world and this year’s US hurricane season was again a devastating one. According to the latest estimates, Hurricane Ian alone cost at least 109 people their lives and caused an estimated 70 billion US dollars in damage (Isidore, 2022). In such catastrophic situations, rapid government disaster relief is needed to mitigate consequential damage and ensure reconstruction in the affected regions. Political decision-makers play a key role in this environment.

Allocation decisions are among the fundamental tasks performed by government politicians. They often have a direct impact on the allocation of state funds, for example when it comes to selecting a new research location for advanced technology, the expansion of public infrastructure or the release of state aid funds in the event of a disaster. Numerous analyses have shown that politicians take not only the common good into account when making allocation decisions but also their own political-strategic considerations (see, for example, Berry et al., 2010; Gehring & Schneider, 2018; Larcinese et al., 2006). Many studies on political influence clearly answer the question of whether there are – on average – politically motivated biases in allocation decisions in the affirmative. What has not been ascertained so far is which decision-making situations are affected by this phenomenon and to what extent? Are politicians always moderately guided by strategic considerations? Or is political favouritism a massive problem in certain situations, while decision-makers shy away from politically motivated allocations in other decisions?

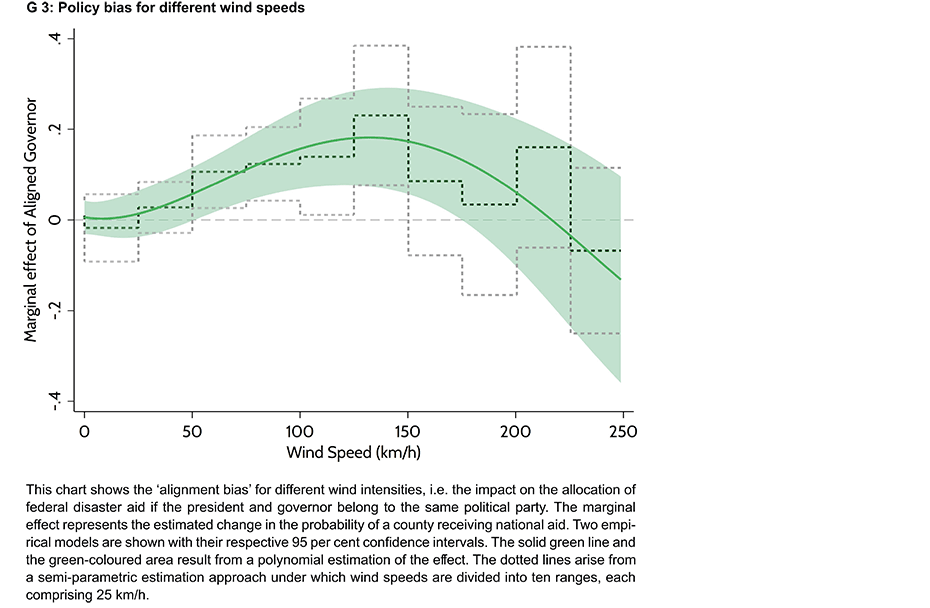

The findings of a new study by Stephan A. Schneider (KOF at ETH Zurich) and Sven Kunze (ZHAW) on the allocation of disaster relief in response to hurricanes in the United States suggest that the latter view is correct: the extent of political bias varies considerably. For very strong and weak hurricanes there is no statistical evidence of political bias in relief allocation. However, when it comes to releasing financial aid after medium-strength storms US presidents favour regions that are governed by their political allies. This effect is particularly pronounced: the estimated political ‘alignment bias’ in these situations corresponds to almost a doubling of the probability to receive government aid funding.

Hurricanes as a natural experiment to determine political influence

The innovation of the present study lies in its generation of precise spatial hurricane data and its combination with political data. In addition, the US federal aid allocation mechanism provides a clear framework for identifying potential political favouritism.

If a state needs assistance to mitigate the consequences of a natural disaster, its governor can apply for federal aid. The decision-making power over the release of federal aid funds after natural disasters lies solely with the president. They can issue a disaster declaration for the counties affected, giving them access to relief payments by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Although the amount of the payments is determined by FEMA, the president decides whether any money is actually paid out.

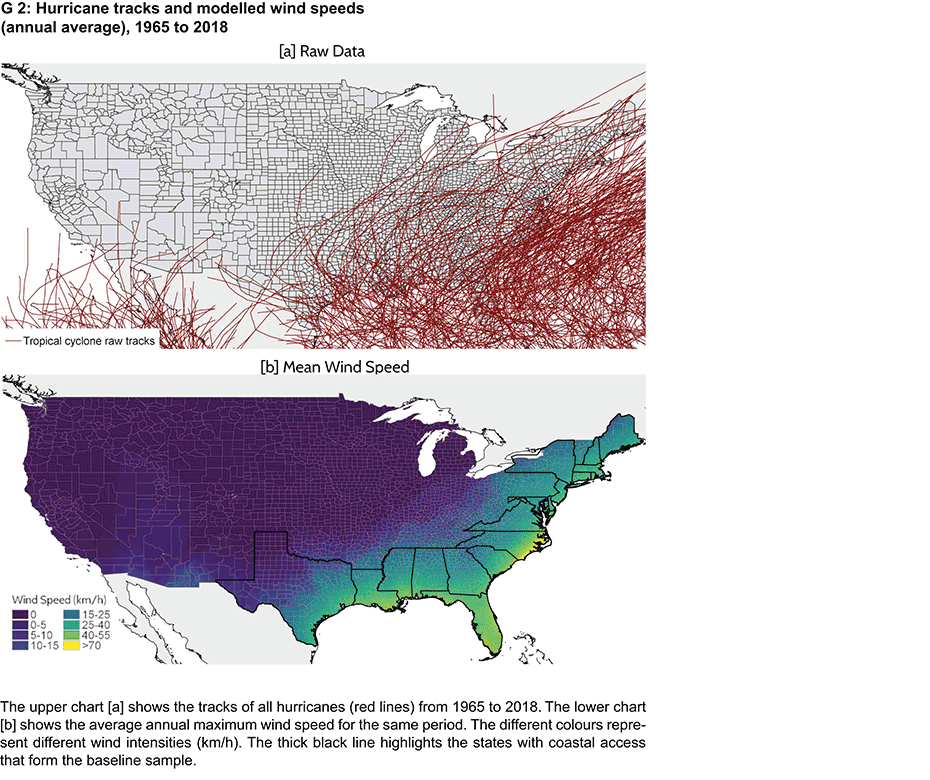

The US is hit by several hurricanes every year. Their tracks are unpredictable (see chart G 2) and their local level of destruction varies both between and within individual storms. In the run-up to a hurricane it is almost impossible to predict whether a location will be hit and, if so, with what intensity. This natural unpredictability over time ultimately allows the researchers to isolate the causal political bias in the decisions. The study uses a meteorological model to estimate the temporal and spatial intensity of hurricanes. This generates the maximum wind speed per county and year for all hurricanes that have hit the US since 1965.

Political bias strongest for medium-intensity hurricanes

For each wind speed the researchers estimate how strong the political influence is for the probability of a disaster declaration. One focus of their work is to calculate the ‘alignment bias’: how much higher is the probability of a disaster declaration if the governor and the president belong to the same political party? While no systematic alignment bias can be identified for very strong and weak wind speeds, it amounts to as much as 20 percentage points for medium-strength storms (see chart G 3). In terms of the disaster aid actually disbursed, this corresponds to about 450 billion US dollars per year that is distributed in a politically motivated manner (about 10 per cent of total hurricane aid). The researchers also find further evidence of an electoral bias: political favouritism is more pronounced in election years and in politically contested regions.

How can these findings be explained? US presidents face a number of very different decision-making situations in the wake of hurricanes. If destruction is extreme, in most cases presidents decide to issue a disaster declaration in the counties affected – whether because of their own sense of justice or because the decision is in line with overwhelming public opinion. Likewise, it is hardly politically justifiable to declare a disaster in regions with very low wind speeds. In these cases the decision is clear. However, there are situations where it is less obvious whether the release of federal relief is necessary or not. Here, political considerations may tip the balance either in favour of or against a disaster declaration. Whether a request for disaster relief came from a party colleague or from a region crucial for the president’s re-election can then be the decisive factor.

Implications for research and practice

In general, we can conclude from these findings that it is important to look closely – including statistically – in order to understand political favouritism. Politicians appear to be aware of the decision-making situations in which democratic control by the electorate is limited, for example because there is less media attention and it is harder to systematically identify unfair decisions. Understanding politicians’ behaviour and adapting the institutional framework to curb political favouritism requires precise analysis of political decisions that goes beyond calculating average effects.

What options are available to remedy the situation in this specific case? One initial approach under the existing system in the US would be for presidents to have to justify their decisions transparently. Depoliticising disaster relief by transferring decision-making power to neutral experts without electoral incentives would also be a constructive approach. Moreover, today’s technology would enable data-based decisions. A system that links the allocation of disaster relief to certain intensity thresholds exists in Mexico, for example (see Del Valle et al., 2020). While improvements have little chance of being implemented in the current polarised environment in the United States, the issue is also highly relevant in developing countries and emerging economies. As climate change evolves, they will increasingly have to deal with more severe natural disasters while having limited financial resources available for disaster relief. Their interest in putting state emergency aid systems in place will also increase. In optimum, such systems should facilitate efficient management of disaster situations and prevent politicians from using these instruments strategically for their own ends.

Publication

Schneider, Stephan A. and Sven Kunze (2022): Disastrous Discretion: Ambiguous Decision Situations Foster Political Favoritism. CESifo Working Paper, 9710.

external page https://www.cesifo.org/node/69260

Further literature

Berry, Christopher R., Barry C. Burden, and William G. Howell (2010): The President and the Distribution of Federal Spending. In: American Political Science Review 104.4, pp. 783–799.

Del Valle, Alejandro, Alain de Janvry, and Elisabeth Sadoulet (2020): Rules for Recovery: Impact of Indexed Disaster Funds on Shock Coping in Mexico. In: American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12.4, pp. 164–195.

Gehring, Kai and Stephan A. Schneider (2018): Towards the Greater Good? EU Commissioners’ Nationality and Budget Allocation in the European Union. In: American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10.1, pp. 214–39.

Isidore, Chris (2022). Hurricane Ian Deals a Devastating Blow to the Uninsured. In: CNN Business. external page https://edition.cnn.com/2022/10/07/business/hurricane-ian-uninsured-losses (October 7, 2022).

Larcinese, Valentino, Leonzio Rizzo, and Cecilia Testa (2006): Allocating the U.S. Federal Budget to the States: The Impact of the President. In: The Journal of Politics 68.2, pp. 447–456.

Contact

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland