The pharmaceutical industry is Switzerland’s growth engine

The pharmaceutical sector has become the largest industry in Switzerland. Demand for its products is hardly subject to any cyclical fluctuations, and its declining prices have so far been more than compensated for by increases in production volumes. Employment in the sector has grown sharply, and pharmaceutical products contribute significantly to Switzerland’s goods trade surplus. However, the size of this industry also entails risks.

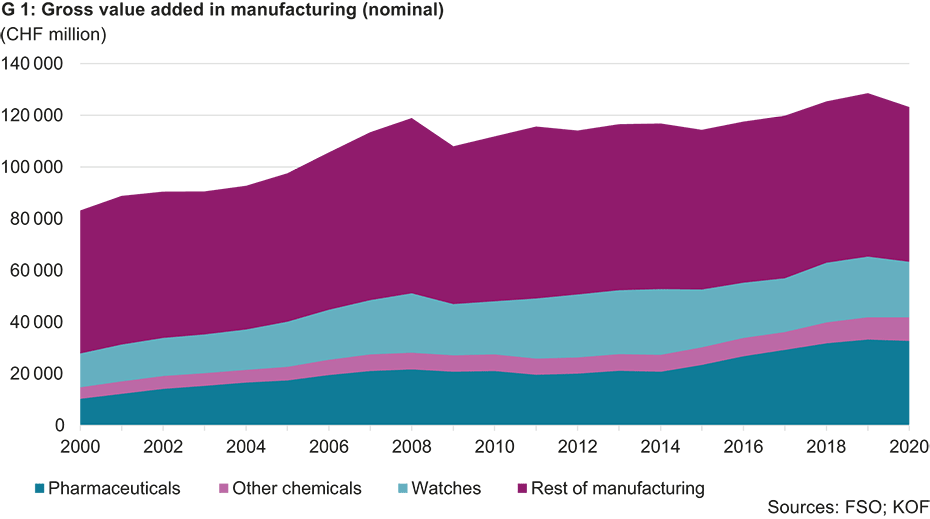

The pharmaceutical sector has been growing rapidly for years. While in 2000 it contributed only 2.3 percentage points to value added, this share grew to 4.8 percentage points in 2020. Annual nominal growth averaged 5.9 per cent, while price-adjusted growth was as high as 9.8 per cent. Total economic value added increased by an average of 2.0 per cent (nominal) and 1.6 per cent (real) over the same period. Full-time-equivalent employment in the pharmaceutical industry rose by 91 per cent over the same period.

Virtually all of the best-known Swiss pharmaceutical firms originated as chemical industrial companies, in which the manufacture of pharmaceutical products was later added as a separate division alongside the others. The chemical industry manufactured various products in addition to its original dyes, which – besides the pharmaceutical ones – included active ingredients for the agricultural sector and a wide range of other chemical products, including plastics and their precursors. In recent decades these pharmaceutical divisions have been split off from the others and continued as independent firms and then merged with other acquired pharmaceutical companies.

Value creation and employment in the pharmaceutical industry have risen sharply over the last two decades

The value added in the pharmaceutical industry has now reached a considerable level and has contributed to the fact that the proportion of economic output accounted for by this industry has remained more or less stable at 18.5 per cent since 2000 (see chart 1).

The sharp increase in value added in the pharmaceutical industry has been accompanied by significant growth in employment. The number of workers employed in the pharmaceutical industry almost doubled over the period from 2000 to 2020. In the chemical industry, as in most other industries, labour input declined during this period. In general, however, employment in the sector grew during the period from 2004 to 2008, when the Swiss franc went through a period of weakness. During the financial crisis – and in subsequent franc appreciation periods – employment fell back again, except in the pharmaceutical industry.

The price performance of pharmaceutical products reveals a pattern typical of high-tech products. New patent-protected products are imported at high prices, which initially decline slowly but later – towards the end of their patent protection – fall more rapidly. While the prices of goods exports and imports over time are often calculated by the so-called mean value indices, these are not used for all product categories in the national accounts. The commodity flows of chemical products, pharmaceuticals, machinery, electronics, watches and precision instruments are adjusted using data from the producer price index or import price index.

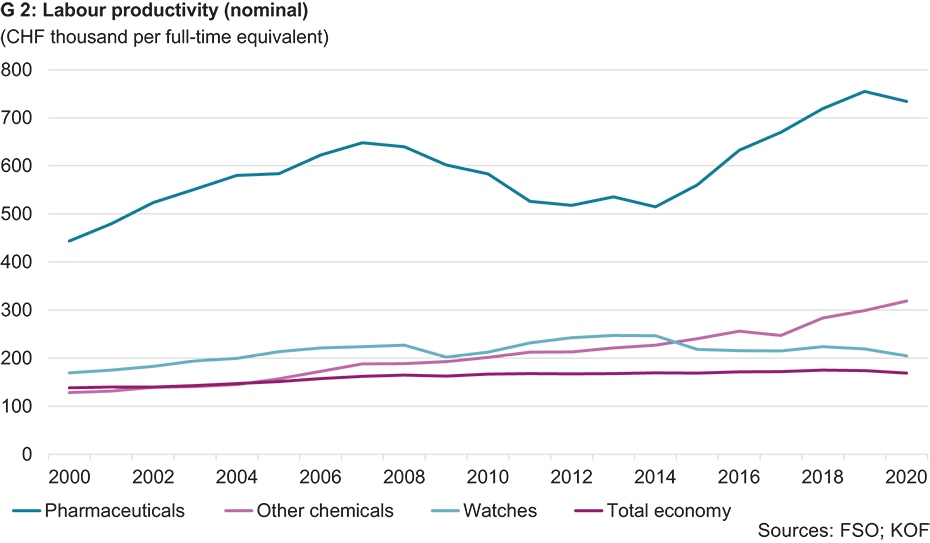

Productivity in the Swiss pharmaceutical industry is very high. In 2019, labour productivity was the highest among the industries reported by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) (see chart 2). Value added per full-time-equivalent was CHF 734,000 in 2020. Other industries with high productivity are energy supply, insurance, wholesale, telecommunications and research & development, although their labour productivity is only half as high. Only in merchanting, which largely forms part of the wholesale trade, is productivity likely to be considerably higher.

Real productivity has increased even more because of the declining prices of pharmaceutical products. This means that although each worker has increased their output well above average, the resulting proceeds have been partially offset by lower prices.

Pharmaceutical products account for over a third of Swiss goods exports

Traditional Swiss goods exports grew strongly during the years before the financial crisis. The period from 2003 to the end of 2007 was characterised by a weak Swiss franc, which gradually depreciated against the euro from CHF 1.47 to CHF 1.66 during this period. Industrial employment as a share of total employment also increased temporarily over this period. Growth in the service industries was subsequently stronger again. Only watch manufacturing and pharmaceutical production and their exports have continued to rise since then. Pharmaceutical products as a share of traditional goods exports thus continued to increase and currently amount to about 36 per cent compared with 11 per cent in 2000.

However, looking at exports alone is not sufficient in order to assess the importance of the pharmaceutical industry in terms of value added. Domestic sales – although relatively small – are added to exports. More important, however, is the fact that services provided by the pharmaceutical industry can be found in other export categories. Pharmaceutical companies own a number of patents, whose revenues from abroad are reported as licensing and patent revenues from service exports. In addition, goods exports of pharmaceutical products are shifting towards merchanting. This occurs when pharmaceutical products manufactured abroad are acquired by a Swiss firm and are sold on to another foreign company, but the products concerned are not physically transported through Switzerland as before but are shipped directly from the production site to the foreign buyer. Such transactions can take place both within the group and between independent companies.

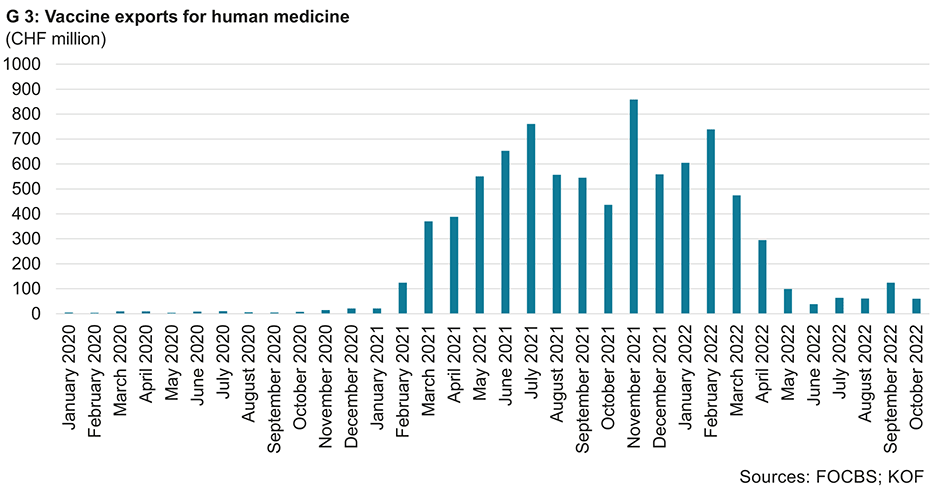

Switzerland has traditionally had a deficit in merchandise trade. This disappeared in the 1990s and trade in goods was then virtually balanced. The surplus grew sharply from 2002 onwards, reaching a maximum of CHF 100 billion in 2021. Of this total, CHF 45 billion came from traditional merchandise trade and CHF 58 billion from merchanting, while the net balance of valuables was minus CHF 4 billion. The pharmaceutical industry made a significant contribution of CHF 54 billion of the 2021 surplus. Of this total, immunological products – whose surplus amounted to CHF 33 billion – accounted for the largest amount, while medicines showed an export surplus of CHF 21 billion. Excluding the surpluses from the pharmaceutical industry, traditional trade in goods with foreign countries would have shown a deficit. The sharp increase in immunological products in 2021 was primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Diagnostic equipment, COVID-19 tests and now also COVID-19 vaccines (see chart G3) caused exports to rise by CHF 9 billion, which was partly offset by the fact that imports grew by CHF 1.6 billion. In the case of medicines, however, the pandemic surplus was lower. Compared with 2019, the surplus fell from CHF 26 billion to less than CHF 21 billion over the following two years – mainly owing to higher imports.

Some Swiss regions are highly dependent on the pharmaceutical industry

However, the strong position of the pharmaceutical industry also carries a risk. It is fairly dominant in some parts of Switzerland. The most prominent example is the Basel region, where this industry has numerous production facilities not only in Switzerland but also across the border in Germany and France. Although there are also firms from other sectors here, if the pharmaceutical industry in general were to suffer a major setback, this would have a noticeable impact on the Basel region. Another example is Visp in the canton of Valais, where a pharmaceutical company is becoming increasingly dominant. For the time being this is a blessing for the region, which has a weak local economy after other industrial companies moved away. However, the new situation also harbours risks for the future.

On the other hand, it is well-known that a region with a high density of knowledge-based firms from a specific field attracts other firms from the same field. These so-called ‘clusters’ have emerged in many areas, and the companies involved benefit both from the transfer of knowledge between participating firms and their employees and from the larger supply of skilled labour. Moreover, since the pharmaceutical industry has the highest sector productivity in Switzerland and is probably itself a driver of the Swiss franc’s appreciation, fears that it could succumb to international competition are not acute at present.