Oil price shock scenario: this is how Swiss managers would react

What would a sharp rise in the price of oil mean for Swiss companies? What are the specific ways in which such a shock would be transmitted to their economic activities? And which sectors would be particularly affected? A KOF survey shows that uncertainty and higher costs are the factors that weigh the heaviest because, according to the managers surveyed, they cause sales losses and price increases.

It happened exactly as many observers had feared: when Russia attacked Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the oil price exploded. The cost of a barrel of Brent crude oil rose from around 93 dollars to over 130 dollars within just a few days – an increase of 40 per cent. The term ‘oil price shock’ quickly gained currency, and fears were raised that the rapid price rise would further fuel inflation in Western countries and slow the global economy.

Politicians and economists were reminded of the first oil price shock, which was one of the worst in history. When the Arab oil-producing states cut their output in 1973 and imposed an embargo on Western countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, the price of oil quadrupled within just a few weeks. The industrialised nations slid into a deep recession with high inflation. Switzerland was hit particularly hard at the time. Its gross domestic product shrank by about 7 per cent and inflation rose to an annual average of almost 10 per cent.

What consequences would an oil price shock have for Swiss companies?

Ever since that first oil price crisis fifty years ago, economists have been investigating the impact of sharp energy price rises on national economies. They are considered to be classic examples of exogenous shocks, i.e. unforeseen, massive changes in supply or demand that market participants cannot influence. In a recently published working paper entitled external page ‘What Do Firm Managers Tell Us About the Transmission Channels of Oil Price Shocks?’, KOF now focuses on the company level. The authors of this study interviewed the CEOs and CFOs of 1,000 companies that are representative of the Swiss economy. One of their objectives was to find out what consequences these managers expect to result from an oil price shock: how much would the price increases affect their company’s costs, prices and revenues? The shock scenario provided was that the oil price rises by 30 per cent – with the economic situation otherwise remaining unchanged – and it then stays 30 per cent above the price previously expected by the individual managers surveyed. Remarkably, although the survey was conducted well before the war in Ukraine, this scenario corresponds fairly closely to what actually happened during the first few months after Russia’s invasion, even though the price of oil has now settled back at around its pre-war level.

Secondly, the authors were particularly interested in why and through which channels – so-called transmission channels – such shocks are specifically transmitted to firms’ economic activities. And thirdly, they wanted to know which sectors in Switzerland are affected differently by oil price shocks and why.

The results:

1. Expected impact on costs, prices and revenues

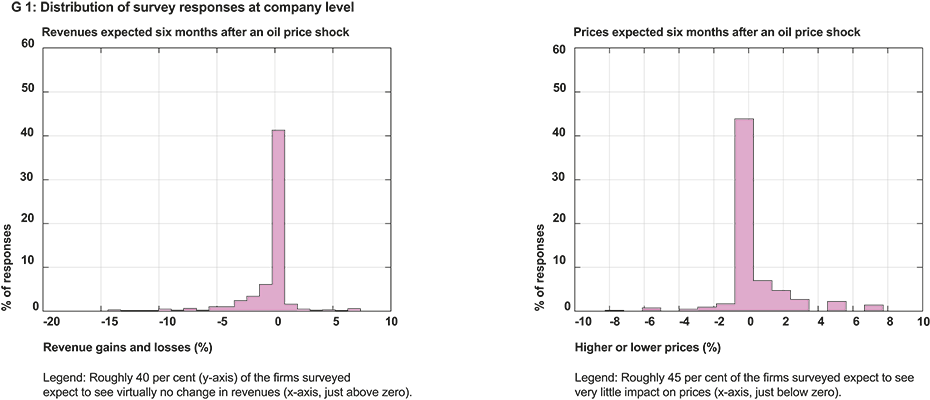

Most managers reckon that an oil price shock of 30 per cent will have only a limited impact on their company’s costs, purchase and sales prices, and revenues. All companies combined, for example, are expected to see only a moderate increase in purchase prices of 1.2 per cent in the next six months (1.5 per cent in 18 months’ time) (see chart G 1). According to the survey, total expenditure will rise by 0.7 per cent in six months’ time (0.9 per cent in 18 months). Moreover, these price increases would only partially translate into higher producer prices in Switzerland: managers expect domestic prices to rise by about 0.5 per cent (0.6 per cent).

However, these averages reflect only part of the reality owing to the heterogeneous composition of the Swiss economy. A considerable proportion of managers fear significant cost increases and price rises of 5 per cent or more. The picture is similarly heterogeneous when it comes to revenue trends. A decline in revenues of only 0.4 per cent in six months’ time (0.6 per cent in 18 months) is expected across all firms. However, a significant number of companies (approximately 8 per cent) expect to incur losses of 5 per cent or more.

2. The transmission channels

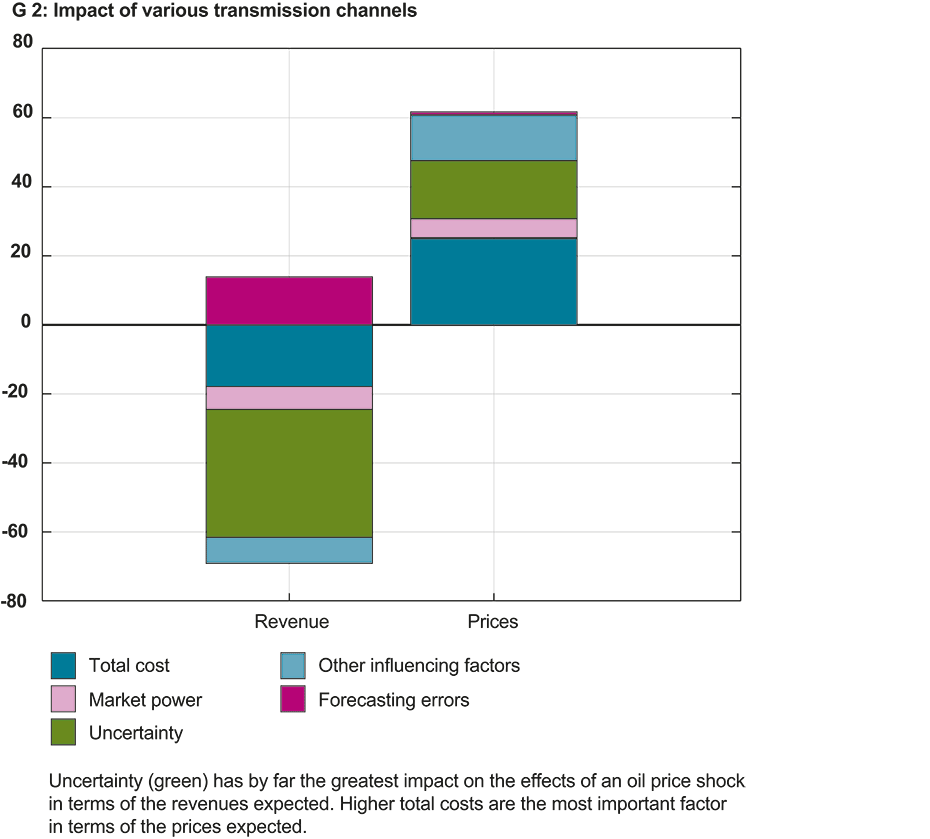

KOF’s study was able to empirically test three transmission channels – frequently mentioned in the theoretical literature – by conducting a representative survey, in some cases for the first time ever. These channels were the effects of oil’s share of output, the degree of market power, and the level of uncertainty about future developments (see chart G 2).

Oil’s share of output: Rising oil prices theoretically push up production costs and – if passed through – producer prices. Both have a dampening effect on economic activity. KOF’s study was now able to clearly confirm this assumption empirically. Companies that need more oil for their business activities in relative terms, i.e. suddenly incur higher costs, actually expect to suffer higher sales losses and price increases.

Market power: Theoretical models assume that an oil price shock’s impact on a firm’s prices and sales figures is determined by its market power. However, this correlation has never been empirically confirmed or refuted to date. KOF’s study has now successfully shown that firms with comparatively high margins (which emphasises their market power) really do expect to see sharply rising prices in conjunction with sharply falling sales. Their market power would enable them to pass on these higher costs to their customers. Companies with lower margins (and correspondingly less market power), on the other hand, cannot afford to do so. Firms facing tough competition are even thinking of lowering their prices despite their higher costs in order to slow an impending downturn in demand.

Uncertainty: In the literature it is assumed that uncertainty about future developments can exacerbate the negative effects that exogenous shocks have on the economy, for example by reducing investment. KOF’s study has now confirmed this theory: company managers who are relatively uncertain about their business prospects expect to incur higher sales losses owing to the oil price shock.

3. How individual sectors are affected

KOF’s survey shows that the various industries are each affected very differently by oil price shocks. Oil’s share of output plays a greater role in the transport and logistics sectors and in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries because their energy needs are relatively high. In contrast, it is practically irrelevant in the financial services sector.

Higher prices, on the other hand, which curb demand, have a stronger impact on tourism and computer/entertainment electronics (and, to a slightly lesser extent, on the machinery and automotive industries and telecommunications). These sectors produce goods and services whose demand is elastic to changes in disposable incomes. Simply put, when money gets tighter because of higher oil prices, people are quick to cut back on taking holidays or buying new appliances.

The Swiss food industry has relatively high market power. Firstly, it is fairly isolated from world markets by protectionist measures. And, secondly, demand reacts relatively inelastically to price changes because it is simply more difficult to save on food than it is in other places. In contrast, the machinery and automobile industries as well as the tourism sector have no market power at all. They are exposed to fierce global competition. Uncertainty affects the tourism industry in particular because its offers can be cancelled at short notice but its investment cannot be altered quickly.

Uncertainty is fatal

The study’s authors finally aggregated the individual survey data to the economy-wide level to determine the contribution made by each transmission channel to the expected impact of the oil price shock. They calculated that, across the economy as a whole, uncertainty plays the most important role in the decline in sales. It can explain about half of this decline. Higher oil prices, on the other hand, are most responsible for the price increases expected in response to the shock. They can explain about 40 per cent of these increases.

The KOF working paper thus shows empirically for the first time which transmission channels play a significant role at the firm level and thus makes an important contribution to research on the effects of oil price shocks.

The working paper by Dirk Drechsel, Heiner Mikosch, Samad Sarferaz and Matthias Bannert entitled ‘What Do Firm Managers Tell Us About the Transmission Channels of Oil Price Shocks?’ is available here: external page https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000584846

“Let’s ask companies directly”

Samad Sarferaz, head of research in the field of data science and macroeconomic methods, explains how the survey was conducted.

You are sitting at the bar and are asked to write your working paper in just five sentences. What do you say?

I would get lost (laughs). As an experiment we asked 1,000 Swiss firms how they would react to specific unforeseen scenarios – in this case an oil price shock. Most CEOs and CFOs generally assume that it would have little impact on their costs, purchase and sales prices, and revenues. However – and this is the really interesting thing – the level of heterogeneity in Switzerland is considerable: there are companies that reacted strongly, while others hardly reacted at all. Furthermore, we found that the competitive environment, uncertainty, and oil’s share of firms’ output play an important role in their reaction to an oil price shock.

The method used in the survey experiment is familiar from the social sciences but less so from economics. Why did you nevertheless decide to confront managers with a fictitious shock scenario?

Time series analysis is generally used to capture causal effects in macroeconomics. It examines data such as interest rates, inflation and economic growth over a period of time. We look for patterns. These patterns are then used to explain the impact of macroeconomic shocks. However, this approach often requires us to make strong assumptions. These assumptions can affect our results so much that they become inaccurate. Moreover, in the aggregate – i.e. in the summary overview – a large proportion of the exciting variations is usually found at company or industry level. In our case, for example, we would only see the moderate effects that oil price shocks have on firms, which is not particularly informative. This only gets interesting when we find out which firms are affected and how. For this information we had to go down to the company level.

In reality, macroeconomic shocks occur not in isolation but often simultaneously. In the interviews – of which there were several – you examined only one shock at a time. Is this another advantage of the method used?

Absolutely. Simultaneously occurring shocks are difficult to identify in the aggregate. For instance, a war may suddenly break out and the oil price rises unexpectedly, the government provides financial support packages or the Swiss National Bank makes surprising monetary policy decisions. It is difficult to distinguish between these individual developments in a time series. So we said to ourselves, ‘Let's just ask companies how they would react to each scenario!’ And from this we then derived the aggregate effects. We started with the oil price shock in 2012. Back then we were among the first to come up with this idea. Today this field is growing rapidly in economics.

How were the companies selected?

They all come from our extensive address pool. KOF has long been conducting regular Business Tendency Surveys and thus obtains unique assessments of the economic situation. The advantage of this approach is that all of these firms know us and are keen to cooperate with us.

How do decision-makers benefit from this working paper?

Our findings help policymakers to gain a better understanding of the individual sectors. This ensures that they are better prepared for future shocks and enables them to make more informed and swifter decisions.

What surprised you about the results?

We are time series econometricians and so, of course, we also applied our tried-and-tested method in parallel. What really surprised us was that when we received companies’ responses to the overall aggregated data, we obtained almost identical results for both methods. Firms see lots, so they are familiar with far more than just their own business. They have a good eye for the economy, understand the situation well and realistically factor environmental criteria and changes into their considerations.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland