Comparing the coronavirus crisis and the financial crisis: eight differences and similarities

KOF Bulletin

With the financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis the world has experienced two severe economic crises within just over a decade. An analysis of the causes, evolution and consequences of these two economic crashes shows that the two crises could hardly be more different.

1. The extent of the crisis

"The coronavirus crisis has triggered the worst global economic slump since the end of the Second World War and dwarfs all previous crises," says Michael Graff, Head of the Business Cycle Research Department at KOF. The Great Recession in the wake of the financial crisis had already eclipsed all of the previous crises that had occurred in the United States and Europe since the Second World War.

2. The causes of the crisis

When researching the causes of the two crises, one quickly comes to the conclusion that they are not comparable in terms of their origins. "The financial crisis was triggered by the bursting of a bubble in the US real-estate market as a result of high levels of household debt,"explains Graff. While in the case of the financial crisis the trigger was located within the economic system, the COVID-19 crisis is completely different with respect to its origin. "The cause of the coronavirus crisis – the outbreak of a global pandemic – was outside the economic system," says Graff.

3. The long-term consequences of the crisis

Graff is optimistic about the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. "The coronavirus crisis has the potential to pass relatively quickly and not cause any lasting economic damage," he explains. It is true that some businesses have gone bankrupt in the wake of the pandemic, which is of course tragic for those affected. In Graff’s view, however, the long-term economic damage caused by this market shakeout and the acceleration of structural change will be limited. The financial crisis, on the other hand, is still being felt more than a decade after it occurred, he said. "The financial crisis has inflicted lasting damage on the economy – we economists talk about ‘hysteresis effects’ – in the form of an adverse macroeconomic equilibrium involving high levels of saving at low interest rates," he said. Many southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece are still suffering from the effects of the financial crisis.

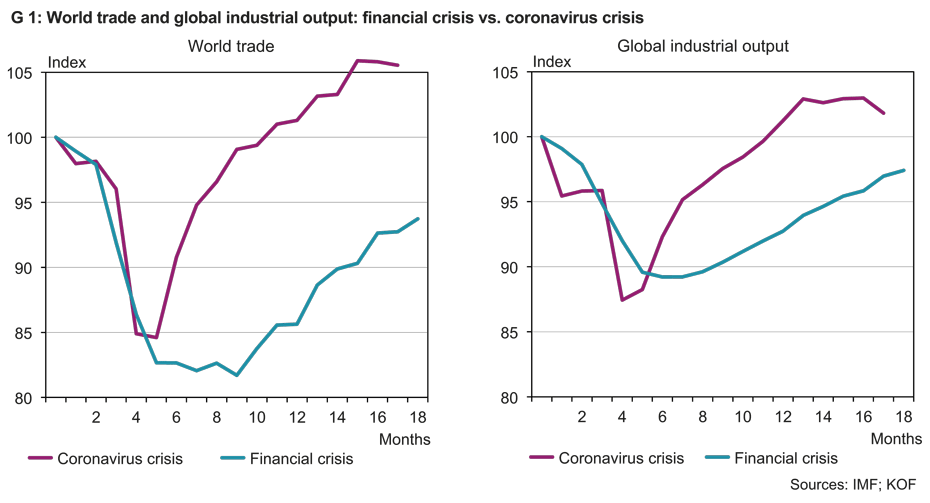

Chart G 1 supports Graff’s theory of a rapid recovery during the coronavirus crisis. World trade and global industrial output, for example, exceeded their pre-crisis levels after just less than a year, whereas both figures were still below their pre-crisis levels even 18 months after the start of the financial crisis.

4. Government intervention

Michael Graff gives his unqualified backing to the Swiss economic policies adopted to combat the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. "Had the government not provided massive support in the form of short-time working and subsidies to the self-employed and businesses hit particularly hard by the crisis, we would have seen bankruptcies, redundancies and, consequently, a loss of human capital during the pandemic." In this respect, he said, policymakers had learned the right lessons from the financial crisis. "Decision-making processes during the coronavirus crisis were efficient and swift. Given the past experience of the financial crisis, when massive fiscal and monetary policy interventions were made, there was no real debate this time as to whether the government should act in the event of such major crises," says Graff.

5. The evolution of the crisis

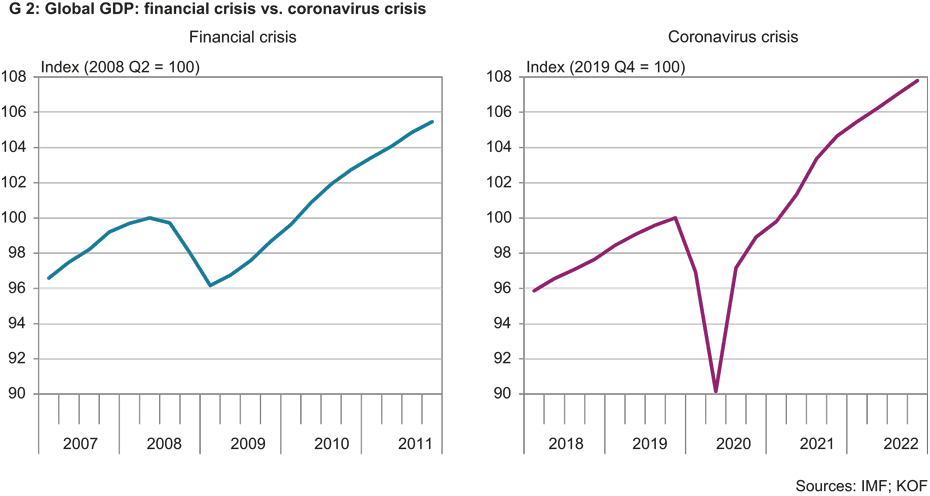

Not every economic crisis is the same. Sometimes the recovery is swift, and sometimes it drags on for years. This is another area where the financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis differ. "The Great Recession after the financial crisis was characterised by a sudden crash and then a recovery, but not a return to the original growth path. The trajectory resembles a root sign," says Graff. The coronavirus crisis, he adds, is characterised by multiple waves, although the correlation between the infectious event and the economy is diminishing thanks to vaccination campaigns. "We’re seeing a multiple W where the volatility – the height of the letters – is getting smaller," he explains.

Chart G 2 shows that although the collapse in gross domestic product (GDP) during the COVID-19 pandemic was more serious than during the financial crisis, the recovery is much faster. According to KOF’s forecast (light-blue area), global GDP could return to its previous growth path as early as 2022.

6. The sectors affected

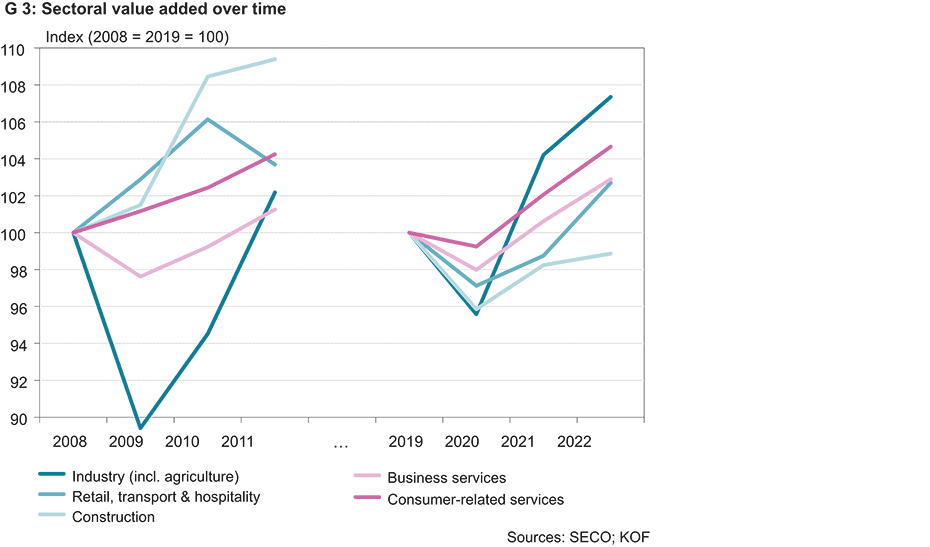

According to Yngve Abrahamsen, Head of the Swiss Economy Section at KOF, the individual sectors have been affected very differently by the two crises. "During the financial crisis the financial sector – primarily the banks – was the first to be hit worldwide. The construction industry in some countries with unsustainable building activity collapsed at around the same time. The contraction in the financial sector, combined with a decline in lending, then dragged down other sectors, primarily the capital-goods industry, but also sectors that produce consumer durables such as the auto industry," he recalls. "During the coronavirus crisis, on the other hand, neither the financial industry nor the manufacturing sector was affected to any great extent, although supply bottlenecks in intermediate products and poorly functioning transport networks caused challenges within the industry," concludes Abrahamsen. However, sectors that were spared by the other crises, such as personal services and the events industry, have been hit hard. The dramatic loss of foreign visitors has seriously impacted the accommodation sector. This, together with additional pandemic-related restrictions, has also affected the catering industry. The non-food retail sector has also suffered, especially during the period when shops were closed. By contrast, online retailing and the pharmaceutical industry have continued to experience an upswing, says Abrahamsen.

Chart G 3 shows that the slump in industry during the financial crisis was significantly greater than it was during the COVID-19 pandemic, while the retail, transport & hospitality and consumer-related services sectors did not collapse at all during the financial crisis – unlike during the coronavirus crisis, when all sectors initially suffered.

7. The labour market

Despite its severity, the coronavirus crisis has not fully impacted the job market, said Graff. "The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is limited. Short-time working sort of froze the status quo ante, so it was easy to unfreeze it when the crisis subsided.” This was different during the financial crisis, he added. "The structural change brought about by the financial crisis was more sustained. For example, the share of value added by the financial industry in Switzerland fell sharply." However, the pandemic is likely to leave structural scars. "Whether business tourism or air travel will ever return to pre-crisis levels now that we can all work from home is unclear," Michael Siegenthaler, head of the Labour Market Section, points out. In addition, the crisis has had a structural impact on the spread of home working and thus on the distances that people commute. And, finally, the increase in online shopping is likely to be permanent and have corresponding potential effects on bricks-and-mortar retail outlets, according to Siegenthaler.

8. The methodological and substantive lessons learned from these crises

There are lessons to be learned from every crisis, including for economics. One lesson to take from the financial and COVID-19 crises, according to Graff, is that we should have no illusions about the vulnerability of our economy. "The long-held view that we now understand the economy so well that there will be no more serious economic crises can no longer be sustained after the experience of the financial crisis and the coronavirus pandemic. Fine-tuning is the only way to prevent and combat such major crises." From a business-cycle research and forecasting perspective, he also argues for more humility. "Such major crises pose a huge challenge for us forecasters. We have learned to track current economic movements relatively well. But making long-term forecasts over several years quickly becomes obsolete and almost impossible in the face of such major crises."

The next KOF Economic Forecast will be available from 6 October in the Press Releases section. In addition, the KOF Nowcasting Lab has recently gone online. Here you will find running estimates of real GDP growth based on the economic data available for Switzerland and the major European countries. The KOF Nowcasting Lab is aimed at all economic actors who rely on the latest data and figures for their calculations. The estimates produced by the KOF Nowcasting Lab are based solely on the data-driven mathematical results of the models, which learn independently from the past and thus continue to develop automatically ('machine learning'). Further information can be found external page here.

Contacts

Dep. Management,Technolog.u.Ökon.

Weinbergstr. 56/58

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland