“The coronavirus crisis has increased inequalities in the labour market”

- Labour Market

- KOF Bulletin

KOF labour market expert Michael Siegenthaler talks about the winners and losers of the COVID-19 pandemic and discusses the outlook for wages and employment once the crisis has subsided.

Some economic theories suggest that economic crises accelerate structural change. Has the coronavirus pandemic also caused creative destruction?

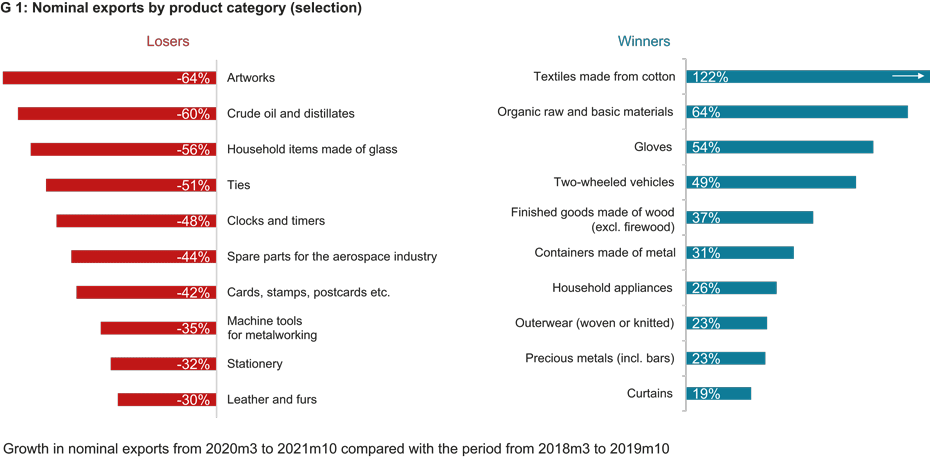

In some sectors the crisis has accelerated the process of digitalisation. However, most of the destruction that has taken place has been relatively random. This can be seen in a breakdown of goods exports by product category (see chart G 1). During ‘normal’ economic crises, companies that are not well positioned are typically hit the hardest. Such cases could possibly be called a market shakeout. However, this has not been the case during the coronavirus pandemic, which has mainly been a matter of either good or bad luck. Demand for outerwear, such as sweaters and gloves, has increased significantly since the outbreak of the crisis. The latter probably stems from the fact that people no longer want to touch surfaces with their bare hands. If you export ties, on the other hand, things have been very difficult simply because people do not wear ties when working from home. This crisis has caused very little creative destruction but plenty of destructive destruction.

On the other hand, analysis by KOF shows that bankruptcies actually declined at the start of the crisis.

Yes. Swift, large-scale political intervention has limited the amount of destructive destruction. Fortunately, the availability of short-time working and business loans has ensured that only a few healthy parts of the economy have been destroyed.

The winners and losers of the coronavirus crisis can be fairly clearly identified. Everything that has to do with software and hardware, such as online delivery services, has gained, while high-contact services in particular have lost out. Is this categorisation still correct if we analyse this in more detail?

In principle, yes. But even within sectors there are differences. For example, an online retailer of business suits and ties has not done well during the pandemic. An online retailer of furniture, on the other hand, has.

You spoke at the beginning about good and bad luck. Has Switzerland been lucky that its economy has not been hit as hard by the crisis as other countries in Europe?

Tourism contributes significantly less to value creation in Switzerland than it does, for example, in Austria and southern European countries such as Italy, Spain and Greece. At the same time, Switzerland benefits from its very strong pharmaceutical industry. This sector is generally not very sensitive to economic cycles, which always helps in economic crises. In addition, the Swiss pharmaceutical industry is involved in the production of vaccines and has therefore even continued to grow during the pandemic. In this respect, Switzerland has suffered less than other countries because of the structure of its economy.

Are the economic winners and losers automatically winners and losers from an employment perspective as well?

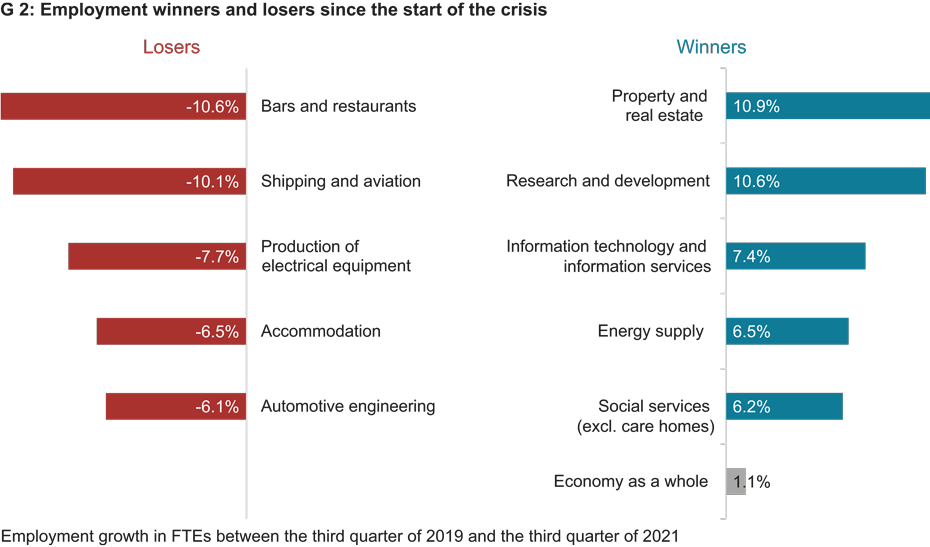

By and large, yes. Companies that are winners have increased their workforces, while crisis losers have reduced their staffing levels (see chart G 2). There are exceptions, however. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, employment has not grown as much as value added. The pharmaceutical boom has mainly benefited value added rather than employment.

Does this mean that wages in the pharmaceutical industry will rise?

They are expected to do so. The sectors that have done well will increase wages, partly because competition for labour has grown sharply during the recovery.

How do you see general wage levels over the next few years?

Our forecasts for real wage growth look fairly gloomy. Crises in Switzerland typically follow a pattern. At the beginning of a crisis wages usually rise at the expense of company profits. This means that those who keep their jobs do not feel the crisis so much economically and often even gain purchasing power because consumer prices remain flat or even fall. During the upswing following the crisis, on the other hand, wages rise less than value added. This is also the case in the current recovery phase. Most of the wage growth is being eroded by inflation, which is high by Swiss standards. We therefore do not expect real wages to rise in 2022.

What distributional effect has the COVID-19 pandemic had on the labour market?

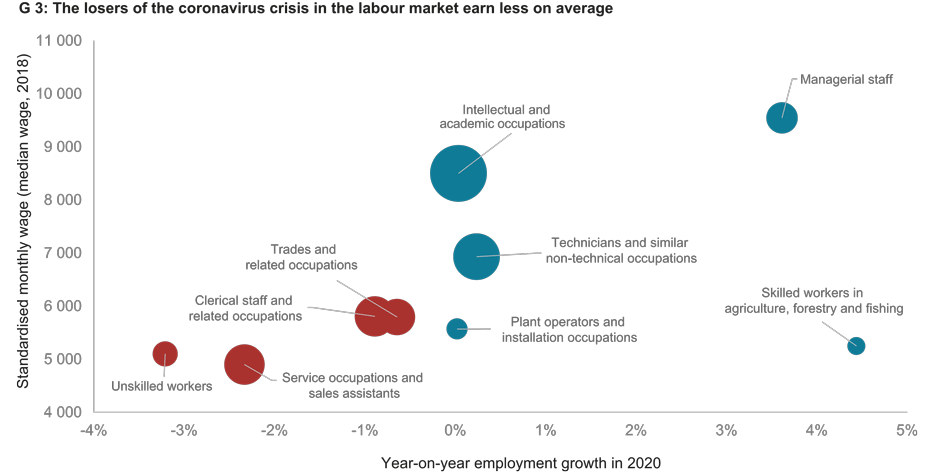

The coronavirus crisis has increased inequalities in the labour market. Low-wage industries such as catering have suffered especially, whereas well-paid and highly skilled workers have rarely lost their jobs and have simply continued to work from home during the pandemic. In 2020, for example, there were no job losses among knowledge workers on above-average salaries (see chart G 3). Employment among managerial staff, who may have been in demand as crisis managers, actually increased by almost 4 per cent.

People in the United States talk about a ‘shecession’ because women there have been hit harder by the crisis than men. Is that also the case in Switzerland?

No. In Switzerland, men and women have been affected equally in almost all dimensions – at least as far as the labour market is directly concerned. What is different is that in previous crises it was primarily men who were affected, as they often work in cyclically sensitive sectors such as construction or industry. During the coronavirus pandemic – unlike the financial crisis, for example – the crisis has hit not only this sector but also contact-related service industries, in which women are typically over-represented. One group that has suffered greatly in the Swiss labour market during the pandemic is foreign workers.

Why?

This is largely due to the distribution of sectors and the employment situation of foreigners. Many foreigners work in precarious conditions and on temporary contracts, often in low-wage sectors such as the catering industry.

Switzerland is traditionally a country of immigration. How has immigration changed in the labour market?

During the first lockdown in 2020 there was significantly less immigration and new employment for cross-border workers. Overall, both immigration and emigration have declined during the coronavirus crisis, while net migration – i.e. immigration minus emigration – has remained fairly constant.

In Switzerland – and even more so in other European countries – many school lessons have been cancelled and the quality of online teaching has not always been able to match that of regular schooling. Does this have an impact on the labour market in the long term, or does this educational gap even out over the course of a person’s professional life?

The relevant studies are fairly clear: investment in education pays off, while lack of knowledge lowers income in the long run. This educational gap can cause lifelong disadvantages in the labour market for the cohorts affected. Because school closures will reduce tax revenues far beyond the duration of the crisis, they have probably been by far the costliest measure in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. In addition, school closures increase inequality because home-schooling gives children of well-educated parents a clear advantage over children with less well-educated parents.

When will the labour market rebalance once the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided?

Structural changes in the labour market – such as those resulting from the increasingly widespread practice of working from home – will take a while to materialise. Unless the pandemic throws us a curveball in the form of further dangerous virus variants, however, we will see the return of something approaching normality in terms of employment in about one to two years. The good news is that the long-term impact of the crisis on the labour market will not be as great as was initially feared. Much of the employment lost will be regained during the recovery phase.

A recording of December’s KOF Economic Forum on the topic of the winners and losers of the coronavirus pandemic is available here.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland