Determinants of Inflation in the Eurozone

- Forecasts

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

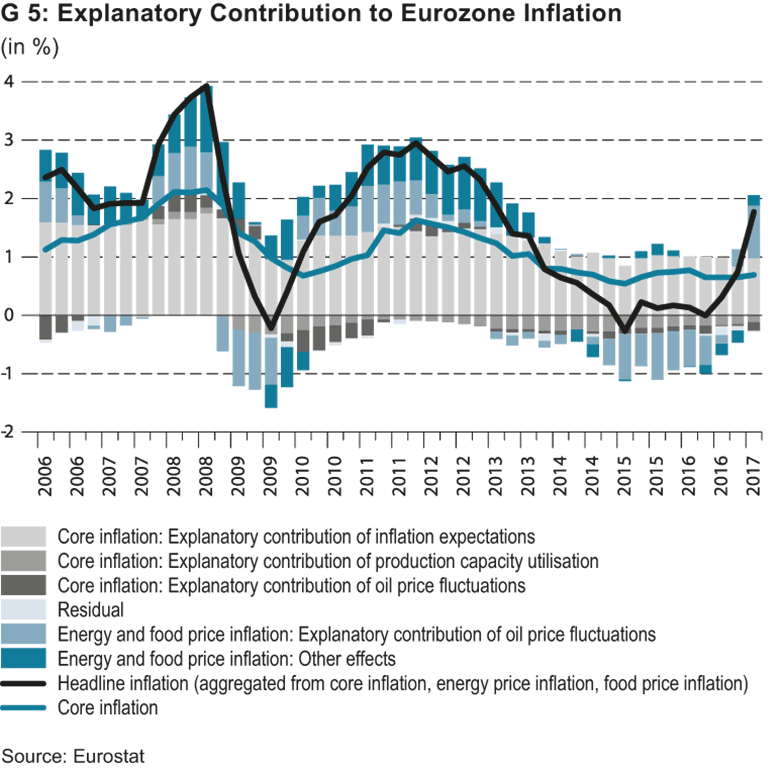

Recently, inflation rates in the eurozone have picked up again. Nevertheless, the core inflation rate remains low. To get a better understanding of the inflation dynamics, KOF has developed an inflation model, which shows that the inflation trend in the past few years was predominantly affected by the decline in oil prices. In the course of the eurozone’s economic recovery and the lapse of the second-round effects of the drop in energy prices, the core inflation rate is likely to rise again.

In the past few months, consumer prices increased substantially in the eurozone. The average inflation rate in the first quarter 2017 was 1.8 per cent, back in the vicinity of the European Central Bank’s (ECB) medium-term inflation target of just under two per cent. As recently as the fourth quarter 2016, the inflation rate still amounted to 0.8 per cent. To a large degree, the rise is due to fluctuations in the crude oil price in the last 12 months. Although, at an average 55 US dollars per barrel (Brent) in the first quarter the oil price was half as expensive as before the big slump around two-and-a-half years ago, it was still 55 per cent higher than in the first quarter 2016. This development is currently affecting consumer price inflation worldwide. If, however, the oil price should undergo another substantial rise in the near future, its impact on the global inflation trend will decline in the course of the year.

All the same, the recent inflationary dynamics are not driven by the oil price effect alone, but also by the recovery of the global economy. Rising demand is probably a key cause of the increase in the prices of crude oil and other commodities. Price pressure on other goods is also likely to increase due to cyclical reasons. Core inflation - the measure of inflation excluding energy inflation and unprocessed food inflation - has hardly risen so far. The core inflation rate was 0.8 per cent both in the fourth quarter 2016 and the first quarter 2017.1 Given the rise in production capacity utilisation and medium-term inflation expectations in the eurozone - the two key determinants of inflation according to the new Keynesian Phillips Curve - low core inflation dynamics actually come as a surprise.2

The KOF inflation model

To arrive at a better understanding of the inflation dynamics in the eurozone, KOF uses an inflation model based on the new Keynesian Phillips Curve, which allows for the variation of estimated parameters over time.3 This model is based on estimates calculated from the data of the years 1999-2017 (first quarter). The core inflation rate is explained by current expectations of future core inflation, the current macroeconomic rate of capacity utilisation and the rate of the year-on-year change in the exchange rate-adjusted oil price. In the version presented below, core inflation expectations are based on the forecasts for eurozone inflation in two years, taken from the Survey of Professional Forecasters at the ECB, in which the indirect effects of past energy and food price fluctuations presumably no longer play a role.

The rate of capacity utilisation in the eurozone is based on the potential estimations of the European Commission. The volatile energy price component is estimated separately using a regression model with time-varying parameters. In conjunction with food prices, this allows for a presentation of the price change of the entire basket of commodities. This separate estimate is advantageous since the trend in energy prices follows different laws than the core inflation trend. While the direct impact of oil price fluctuations on core inflation is relatively low, it may come with a delay due to so-called second-round effects; in contrast, the impact of oil price fluctuations on the energy component, and hence headline inflation, is relatively substantial in the short term.

Inflation decline primarily due to oil price

Between the end of 2011 and the middle of 2015, the inflation rate dropped from 2.8 per cent to just below zero per cent. According to the model results, this development was primarily due to the oil price trend (see G 5). The latter had both a direct impact via the energy price component and an indirect effect via core inflation. In addition, low capacity utilisation, which started in 2013, increasingly had a restraining effect on prices. Since 2015, the production gap in the eurozone has been closing slowly, which has led to a gradual decline of the restraining effect on prices. At the current margin, however, the restraining effect is still present. Nevertheless, a much more important factor explaining the low dynamics of the core rate are inflation expectations. On the one hand, two-year inflation expectations were regressing, on the other hand, the correlation between realised inflation and expectations was weakening. In the period between the end of 2012 and the middle of 2015, this factor alone accounted for as much as 0.6 percentage points. Recently, the decoupling of inflation expectations from realised inflation has stabilised once again.

However, headline inflation is primarily driven by the trend in energy prices. In 2015 and the first three quarters of 2016, energy prices exerted significant downward pressure. The effect petered out towards the end of last year, which explains the sudden jump in inflation rates in the last few months. While the oil price already had a positive direct impact on headline inflation in the fourth quarter 2016 and the first quarter 2017, this was not yet true for the indirect impact via core inflation.

Analysis of the recent inflation trend suggests that the low inflation rates of the past few years were primarily a consequence of the decline in oil prices. The core inflation rate is currently being restrained by the remaining production gap and the spillover effects of the energy prices. Once the expected rise in capacity utilisation occurs and there are no further spillover effects, core inflation is likely to pick up again.

(1) The latest decline in March 2017 from 0.9 per cent to 0.7 per cent is due to a calendar effect. While Easter last year was in March, this year the holiday was in April. As a consequence, package holiday prices were substantially lower than in the previous year. In April, this is likely to result in a significant rise in package holiday prices in year-on-year comparison.

(2) Cf. e.g. Galí, J. (2015): Monetary Policy, Inflation, and the Business Cycle: An Introduction to the New Keynesian Framework and Its Applications, Princeton University Press, 2. Edition.

(3) Cf. KOF Analyses, Autumn 2014..

Contact

No database information available

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland