Eurozone Debt (2/3): Financial Sector

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

The second of three articles on Eurozone debt is dedicated to the financial sector. During the crisis years, many financial firms were criticised, inter alia, for their dependency on public support measures. Since then, a few changes have been introduced in the currency union’s institutional regulations, and systemic risks have been reduced in many countries, albeit not in all of them.

Since, in the case of government budgets, it is difficult to determine equity capital as a parameter, economic performance is often used as a benchmark for acceptable debt levels (see first article on public of household debt in the February Bulletin). By contrast, in the case of private companies and especially banks, the relevant parameter of debt sustainability and hence credit protection is the debt-to-equity ratio, or financial leverage.

For a long time, implied disincentives such as the ‘too-big-to-fail’ problem led to a socially inefficient level of risk adoption among numerous European banks. During the financial crisis, this was reflected by insufficient capital adequacy, which necessitated government support measures in the case of institutes of systemic relevance. As a consequence, the European banking union was established in 2014 with the aim of enhancing the resilience and harmonisation of the financial system. The banking union is based on a uniform set of regulations which are binding on all financial institutions in the European Union. In specific, this includes regulations pertaining to capital adequacy and liquidity requirements, the resolution of failing banks and a deposit guarantee scheme.

The first pillar of the banking union consists of the Single Supervisory Mechanism affiliated with the European Central Bank (EBC), which supervises approximately 120 significant 1 institutes and hence 82% of all bank assets in the Eurozone and the participating EU member states which are not part of the Eurozone. Banks which are not classified as significant continue to be subject to their national supervisory authorities. The latter are supported by the European Banking Authority (EBA), which was established in 2011. The EBA develops supervisory standards based on the Basel III provisions, promotes exchange between national supervisory authorities and carries out stress tests.

The second pillar of the banking union is the Single Resolution Mechanism, which ensures uniform regulations pertaining to the orderly resolution or restructuring of illiquid banks and provides a common resolution fund. While the ECB is responsible for the resolution of significant institutes, all other banks are subject to their national authorities. This is to ensure that losses are borne by the creditors and government bailouts are no longer permitted. The resolution of the Spanish ‘Banco Popular’, for instance was successful in this respect, while government funds were still involved in the resolution of struggling banks in Italy last year. The introduction of a deposit guarantee scheme is currently being discussed as a third pillar.

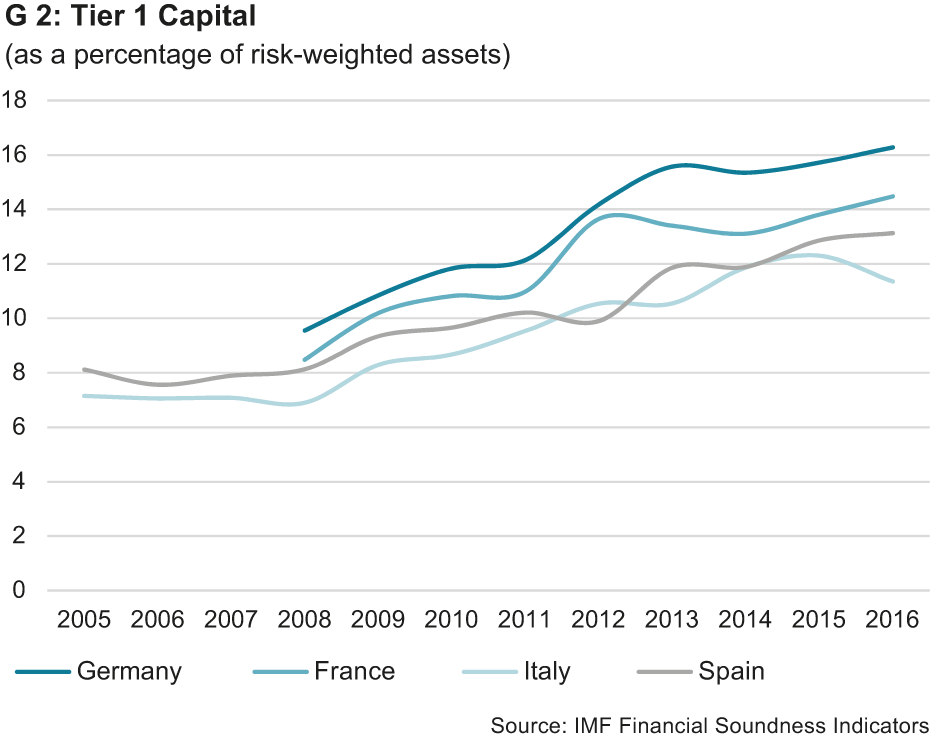

Thanks to gradual debt reduction since the financial crisis, the regulatory provisions are now fulfilled, although substantial differences persist between the individual countries. A relevant parameter in this context is the tier 1 capital ratio, which indicates the percentage of a bank’s risk-weighted positions that are covered by equity. The average of Eurozone core capital in relation to risk-weighted assets has risen from 8% in 2007 to 14% (see G 2).

While Germany has the highest capital adequacy ratio amongst the big countries, the ratio has recently declined in Italy. Core capital held by Eurozone banks has also dropped in relation to unweighted assets, namely by one percentage point to approximately 6.5%. On the one hand, this is due to a decrease in high-risk investments, on the other hand, additional equity capital has been accrued via profit retention and capital increases. However, this adjustment of bank balance sheets has affected the banks’ lending activities and is likely to have played a role in the slow recovery of the Eurozone economy.

Risks inherent in Italy’s financial sector

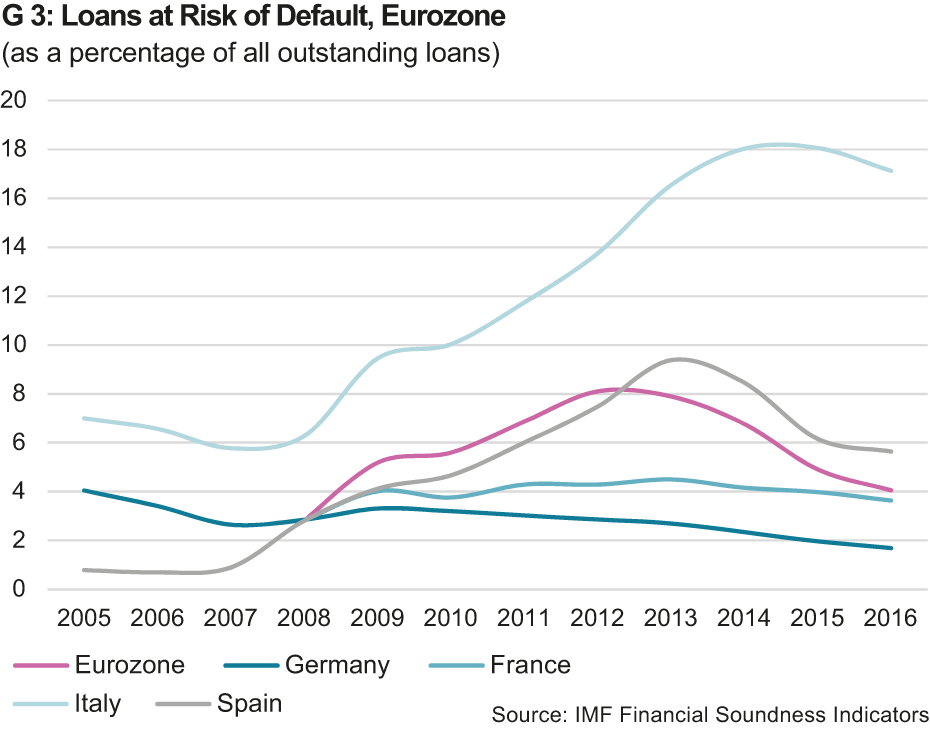

A further indicator of debt sustainability in the financial sector, albeit on the asset side, is the percentage of loans at risk of default 1 in all outstanding loans. Although this percentage has declined slightly in 2014, it is still very high in individual countries (see G 3). In Italy, the percentage almost tripled between 2008 and 2016 and is currently close to 17%. Due to the size of the Italian financial sector, Italy now accounts for around one third of all non-performing loans in the Eurozone.

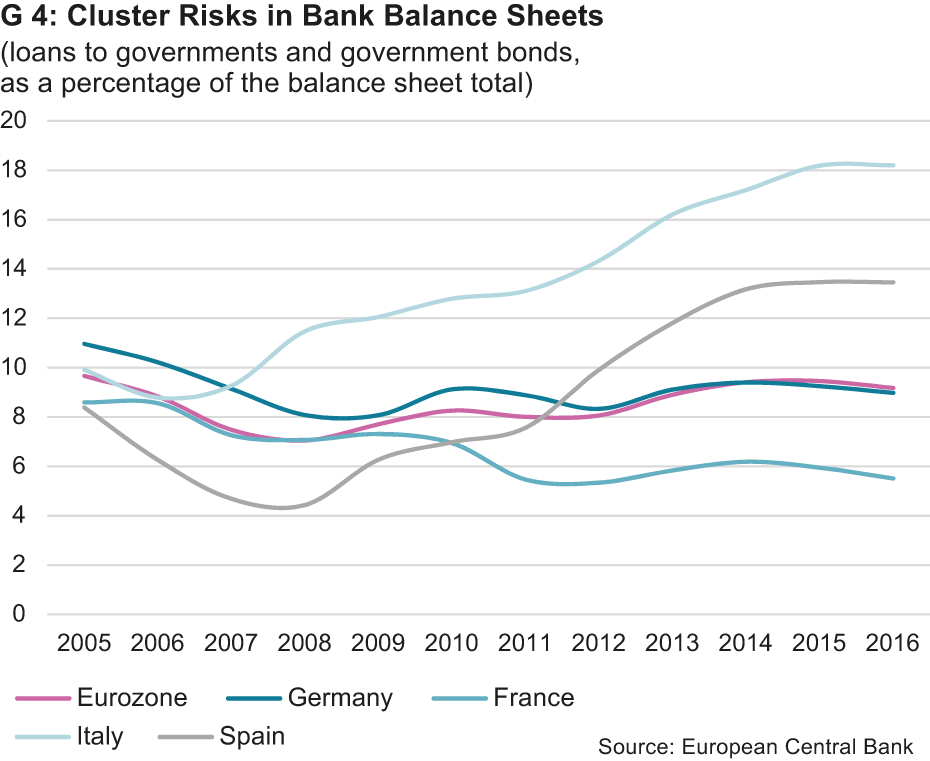

The problems faced by the Italian banking sector are also reflected by the asset side of the balance sheets. At 11%, the share of domestic government bonds in Italian bank balance sheets is twice as high as the Eurozone average. The situation is similar for loans extended to the government, which make up 7% of the balance sheets (see G 4). Should the government get into financial difficulties in the case of a crisis, this would impact directly on the solvency of the domestic banks. Combined with a high percentage of non-performing loans and the Italian banks’ low tier 1 capital ratio, this could result in bankruptcies.

Do the supervisory authorities face a conflict of interest?

The banking union also pursues the aim of reducing interaction between governments and domestic banks in order to avoid any associated mutual contagion in the future. However, there is a risk that placing the European supervisory mechanism under the umbrella of the ECB may lead to a conflict of interest with the latter’s monetary objectives.

[1] Significant banks are defined as banks with total assets in excess of EUR 30 billion, assets in excess of 20% of the GDP of the participating country and a minimum of EUR 5 billion, or the three biggest banks in each participating country.

[2] Loans are considered to be at risk of default or non-performing when the debtor has failed to meet their payment obligations for a period of 90 days or more.