Smoothing of Tax Revenue and Modification of the Debt Brake for the Canton of Neuchâtel

- Fiscal Policy

- KOF Bulletin

The high volatility of certain revenue categories confronted the Canton of Neuchâtel with budgetary policy problems in past years. Unexpected and sometimes significant changes made it difficult to conduct budgetary policy. In particular, unexpected revenue shortfall made it necessary to make adjustments to ensure compliance with the requirements of the debt brake. Therefore, the KOF recommends the implementation of a smoothing mechanism along with a budgetary rule based on the trend revenue.

Volatility within cantonal revenue and forecasting errors

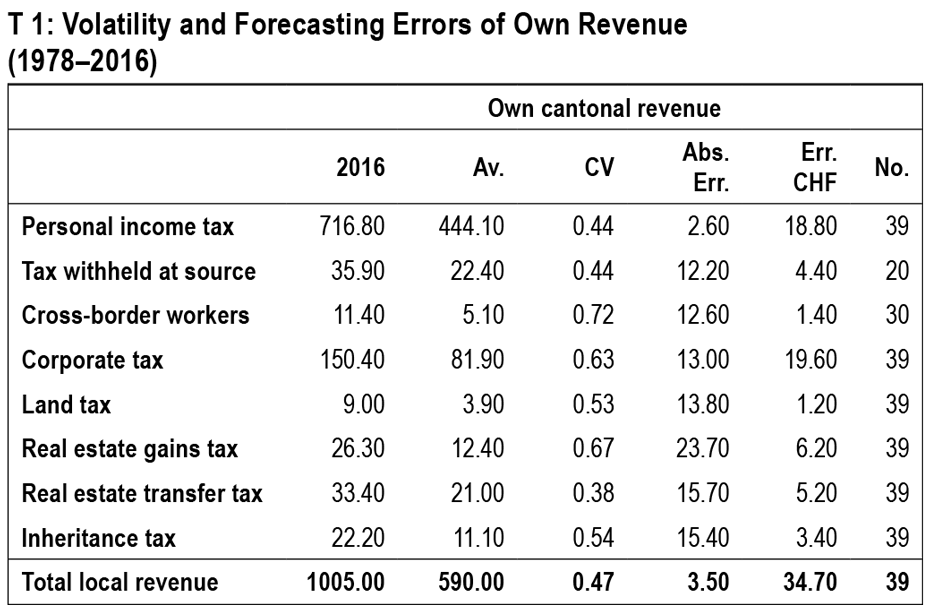

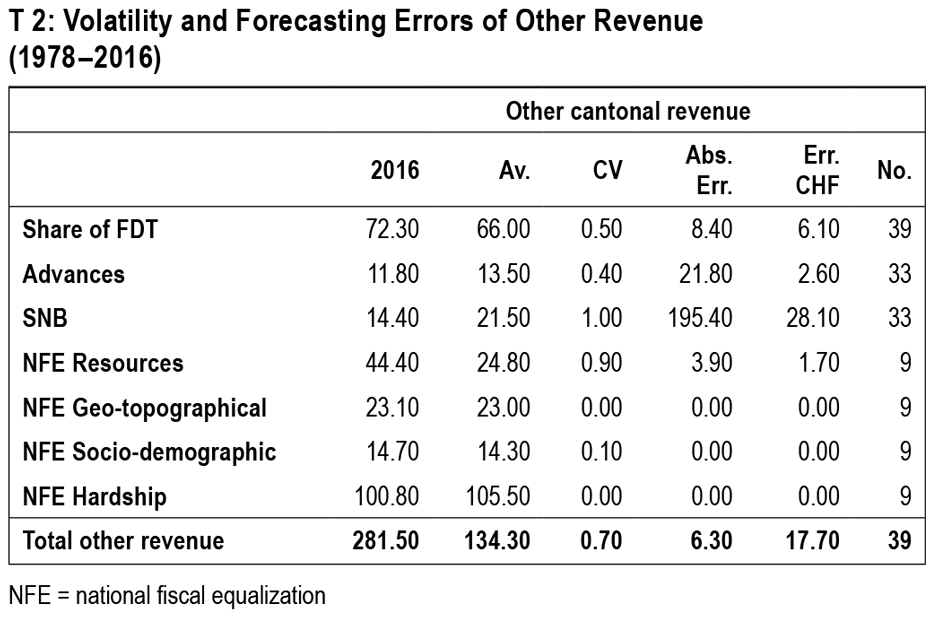

In order to be able to propose a revenue smoothing mechanism, it is necessary first and foremost to identify the categories that pose the greatest problems from this point of view. Tables T1 and T2 quantify volatility along with the forecasting errors for different categories of cantonal revenue. These tables present, in order, the amount of revenue collected in 2016 in millions of Swiss francs, the average for the period (Av.), the coefficient of variation (CV) , the average absolute forecasting error as a percentage of revenue booked1, the equivalent in Swiss francs in 2016 of the average absolute error and finally the number of periods in the series (P).

The coefficient of variation offers a measure of volatility which is comparable for different revenue categories and confirms that revenue collected from corporate tax, the share of federal direct tax (FDT) and revenue from the resource equalisation mechanism is highly volatile. Furthermore, the average absolute forecasting error in Swiss francs in 2016 quantifies the impact on budgetary policy of the difficulty in forecasting this revenue.

With an average absolute error in CHF of between 19.6 and 6.10 million, corporate tax and the share of FDT have been particularly problematic for the conduct of budgetary policy and require a smoothing mechanism to be put in place.2

Revenue smoothing mechanism

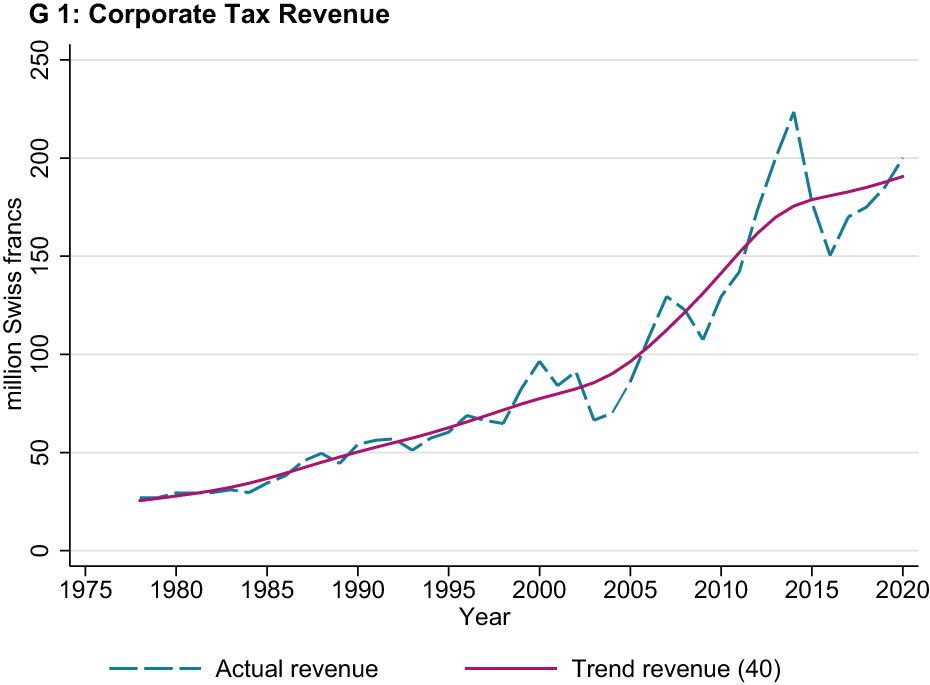

The smoothing mechanism recommended is based essentially on three elements, specifically the creation of a smoothing reserve in the balance sheet, the definition of a rule governing payments into/out of the reserve, and the calculation of a trend revenue level. In this contribution, we use corporation tax as an example in order to illustrate the smoothing mechanism called for. The trend revenue level has been calculated with the assistance of a HodrickPrescott filter (Hodrick and Prescott, 1997)3. The degree of smoothness imposed by the filter on the revenue data set is dependent upon a lambda parameter, which we have set at 40 according to the procedure recommended by Pollock (2004)4. Graph G1 illustrates in blue the actual corporation tax revenue and in red the trend level calculated with the assistance of the HP filter.

The difference between these two curves determines the amount of revenue that is to be credited to/drawn down from the reserve. For reasons of transparency and in order to facilitate the assessment of the mechanism, we recommend that a reserve be created for each revenue category. In the specific case of corporation tax, we recommend an initial allocation to the reserve of between CHF 3 and 55 million, depending upon the revenue dynamic at the time of its creation.

Modification of the debt brake

The volatility of the different revenue categories complicates the conduct of budgetary policy since, due to the variations in revenue, significant adjustments need to be made on the expenditure side over the very short term. In order to avoid such adjustments and to smooth out the variation in expenditure over time, we recommend a modification of the debt brake mechanism. In particular, the reference to a maximum spending overshoot of 1% should be removed and replaced by a budgetary rule known as “trend revenue”, namely a rule that sets the level of spending at the level of trend revenue. Such a fiscal rule requires the fiscal balance before payments into/out of the smoothing reserve to fluctuate according to business cycles, whereas expenditures should be kept at the level of trend revenue irrespective of the phase of the business cycle. With specific regard to the stabilisation of public spending, the superiority of a budgetary rule of this type over other alternative mechanisms, including in particular those based on moving averages or on a model identical to the Federation’s debt brake, has recently been demonstrated.5

1) This indicator measures the average over the period of the absolute difference between budgeted and realised revenue in each considered year in percent of the realised revenue. The use of the absolute value means that both positive and negative deviations are considered as positive values. This prevents that positive and negative deviations offsets eachother when the average of the deviations is computed over several years..

2) The significant forecasting errors for the share in the profits of the Swiss National Bank (SNB) are essentially due to the years 2013 and 2014, when the SNB failed to pay a dividend in 2013 and then paid double the amount in 2014.

3) Hodrick, R. and E. Prescott (1997): Postwar U.S. Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 1–16.

4) Pollock, D.S.G. (2000): Trend estimation and de-trending via rational square-wave filters, Journal of Econometrics, Volume 99, Issue 2, pp. 317–334.

5) Landon, S. and C. Smith (2017): Does the design of a fiscal rule matter for welfare?, in Economic Modelling, Volume 63, 2017, pp. 226–237.

Contact

No database information available