Why Is World Trade so Weak?

- KOF Bulletin

- World Economy

World trade has only been recording moderate growth in recent times. This article will consider the reasons for the lack of dynamism.

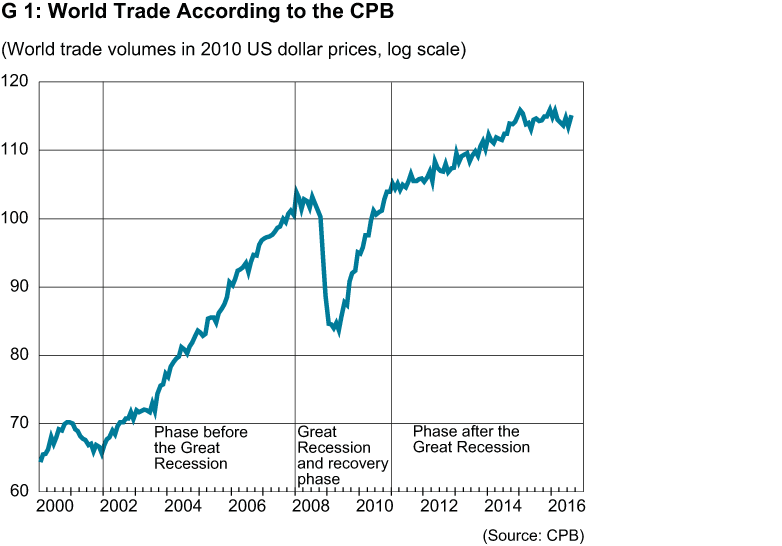

For around six years, world trade has been developing much more slowly than it was before the Great Recession (see G 1).[1] According to figures from CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, between January 2002 and December 2007 world trade grew each month by an annualised average of 7 per cent; the figure for the period between January 2011 and September 2016 is only 1.6 per cent.

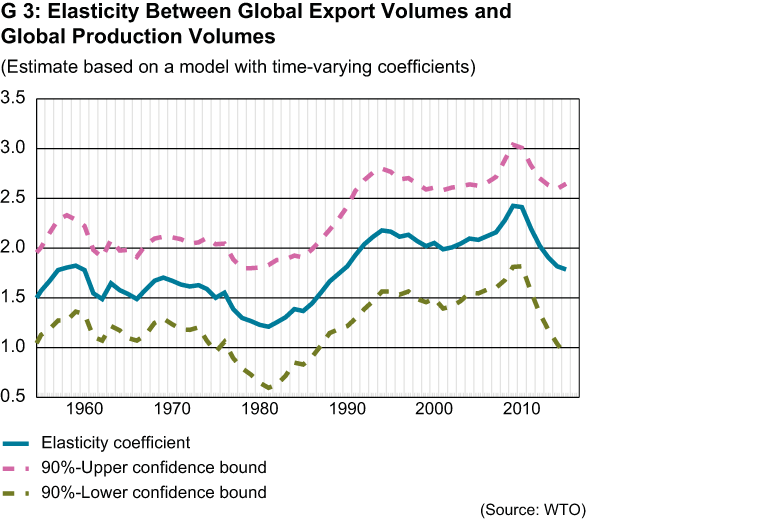

Is the weakness in world trade actually a trade-specific phenomenon or does it simply reflect a general weakness within economic activity on a global scale? In order to answer this question, the KOF has estimated the correlation between world trade in goods and world industrial production with reference to a model with time-varying coefficients.[2] Industrial production can account for the variance in trade, at least in part. However, it is noticeable that the elasticity between trade and industrial production has fallen significantly since the middle of 2009. According to our model, a one per cent increase in economic activity in 2009 was associated with an increase in trade of around 1.6 per cent; in 2016 on the other hand the attendant increase was only around 1.2 per cent.

Which regions of the world have contributed most to the weaker dynamic of world trade?

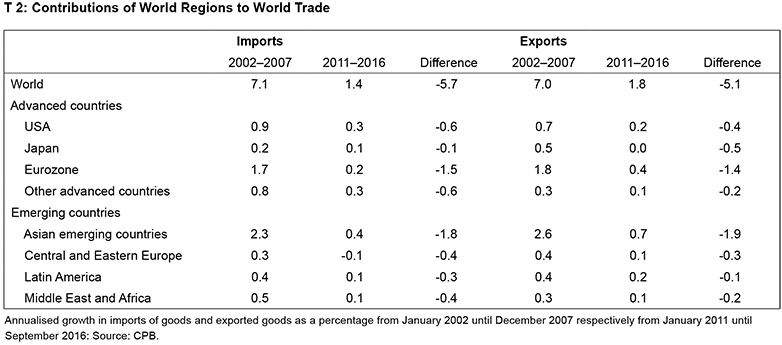

The Asian developing countries and the Eurozone provided the largest contribution to the decrease in the rate of expansion of world trade (see T 2). Nearly 60 per cent of the decline in world imports and two-thirds of the decline in world exports is attributable to these two regions. Estimates on a regional level also show that this fall in elasticity between trade and industrial production is being driven by these two regions and Japan. For the USA and the other regions on the other hand, no (significant) fall in elasticity can be noted.

Assessment based on a long-term historical comparison

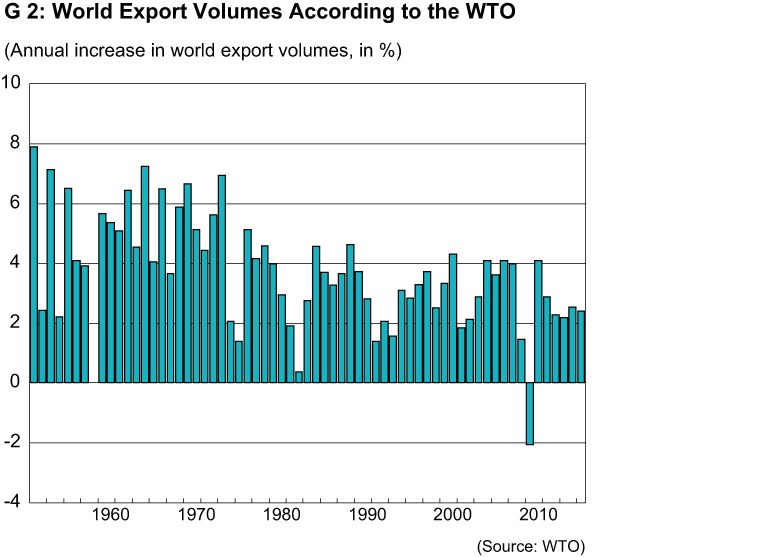

Empirical analyses of world trade mostly use data stretching back to 1970 at the earliest. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) however published an annual data series for world export volumes which dates back to 1950 (see G 2).

An estimate of elasticity between world export volumes and world production since 1950 shows that elasticity was quite low until into the 1970s (see G 3). However, world production increased relatively strongly during this period with the result that, despite low elasticity, there were high increases in the volume of world exports. Elasticity increased at the start of the 1980s and remained relatively high until the end of the 2000s. This statistical evidence is considered to reflect the opening up and increasing integration of China into the world economy in addition to global trade liberalisation.

The increased elasticity ensured that world trade remained dynamic – even though world production did not increase over the period between 1980 and 2010 as strongly as it did prior to 1980. From the end of the 2000s, elasticity started to fall again. Since world production has only expanded relatively weakly since 2012, the last four years – and probably also this year – have resulted in historically low rates of growth in world trade (see G 2).

And Swiss foreign trade?

In Switzerland, the increases in foreign trade during the period after the Great Recession were much lower than during the years leading up to it. Whilst the annualised rate of growth in Swiss trade for the previous quarter averaged 5.5 per cent between 2002 and 2007, the equivalent figure for the period 2011 to 2016 averaged only three per cent, and was thus around 2.5 percentage points lower.

The fall in expansion rates of growth has been particularly marked for exports. It should be noted in this regard that the period from 2002 until 2007 coincided with a depreciation of the Swiss franc, whilst the franc has significantly increased in value between 2011 and 2016, in particular against the euro. Interestingly, the slowdown in Swiss foreign trade relates exclusively to trade in goods, whilst trade in services has accelerated.[3]

An estimate of the above model for Switzerland shows that elasticity between Swiss foreign trade and production has fallen significantly since the end of the 2000s. At least in qualitative terms, the dynamic for Switzerland resembles that of the Eurozone.

How will world trade develop in future?

The previous analysis suggests that world trade will remain relatively weak over the longer term. Trade integration in Europe and throughout the world is expected to make significantly less progress in future than it has over the past decades. There may even be some level of de-integration. In terms of European trade, which is important for Switzerland, it is forecast that the southern European countries will generate reduced demand for imports over the longer term than over the period running up to the Great Recession. Nevertheless, there are indications that Germany will increasingly be the main driver of demand.

The increase in trade with China, which accounts for around 40 per cent of the aggregate figure for Asian emerging countries, will slow down as a result of the structural shift from investment and industry-driven growth to consumer and service-based growth. The reason for this is that Chinese consumer goods account for a significantly smaller share of imported goods than Chinese investment goods. However, this structural shift also offers major opportunities for a number of Swiss export industries.

Forecasting model for world trade

World trade forecasting is highly challenging from a methodological perspective: relatively few global indicators are available for providing an aggregated forecast of world trade – at any rate compared to national statistics. In addition, the creation of a world trade forecast on the basis of disaggregated export and import forecasts of all individual countries is extremely time-consuming. The KOF has resolved this problem by using a hybrid forecasting model. It first generates export and import forecasts for important countries from the world economy and the European Union on the basis of multiple models. It then calculates the aggregate from the trade figures for individual countries and models the correlation between this aggregate series and comprehensive world trade using a Bayesian estimation model. A forecast for world trade is devised on this basis.

[1] In this article, the concept of (external) trade means the average of exports and imports.

[2] Estimate based on monthly CPB figures from 2000. World industrial production serves as a proxy for global economic activity.

[3] The above analyses of world trade related only to trade in goods. The incorporation of trade in services could change the picture. Global data concerning real trade in services are however only fragmentary.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Contact

No database information available

Contact

No database information available