How does inflation come about?

- Inflation

- KOF Bulletin

Recently there have been increasing warnings of a resurgence of inflation. This paper presents the results of an empirical study of the main factors that have affected inflation over the past two decades.

How does inflation come about? Despite the extensive literature on the subject, there are a number of unanswered questions. No single approach has managed to satisfactorily explain the inflation process. A large number of possible determinants are mentioned. The relevant literature mainly emphasises economic, institutional, technological and political factors, which can be grouped into eight economic theories: (1) natural resources, (2) demographics, (3) globalisation and technology, (4) money, credit and the business cycle, (5) monetary policy strategies, (6) political and institutional characteristics, (7) public finances and (8) past inflation.

Studies show mixed results overall. However, they are often based on a cross-section of countries with low inflation, short time periods and a limited number of predictors. Methodologically the focus is on linear relationships, although we cannot assume linear relationships between the explanatory variables and inflation. Moreover, only a few robustness tests using alternative estimation methods or model comparisons are performed.

Mixed-model approach

This is the motivation for a new study (Baumann et al., 2021a), in which the authors empirically compare the most important theoretically motivated models with regard to the variables affecting inflation. In addition, a machine-learning approach is included in the study and compared with the theoretically based models.

Results

(i) Energy prices and rents

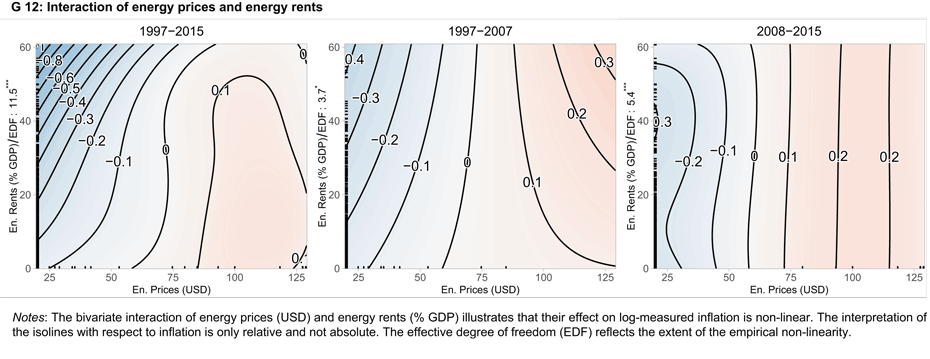

The interaction between energy prices (mainly oil) and energy rents1 emerges as the most important determinant of inflation. Chart G 12 summarises the evidence using an isoline plot. The transition from a blue area to a red one indicates rising inflationary pressures, while the transition from a red area to a blue one suggests the opposite. The black isolines can be used to infer the strength of these effects. The left panel covers the entire observation period, the middle panel spans the period before the 2007/2008 global financial crisis and the third panel covers the years thereafter. As shown in the left panel, the strongest inflationary effect arises when energy prices are low and energy rents are high (upper left corner). In this combination, an increase in energy prices results in a strong acceleration of inflation, which persists up to a level of $90. In contrast, when energy rents are low, a rise in energy prices is still associated with higher inflation, but less so than when energy rents are high. When the price exceeds $80, this effect flattens out. A comparison between the middle panel and the third panel suggests that this interaction has weakened since the global financial crisis.

ii) Demography, technological progress and globalisation

The ageing of society is often mentioned in the literature and media reports as an important influencing factor. Theoretical and empirical studies have come to different conclusions. In some, the ageing of society has an inflationary effect, in others a deflationary effect. This study shows that demographic developments have contributed to the above-mentioned deflationary trend. However, they were less important than the interplay between energy prices and rents. Increasing investment in information and communication technologies (ICT) raises inflation. Technology outperforms common globalisation proxies such as trade and financial openness.

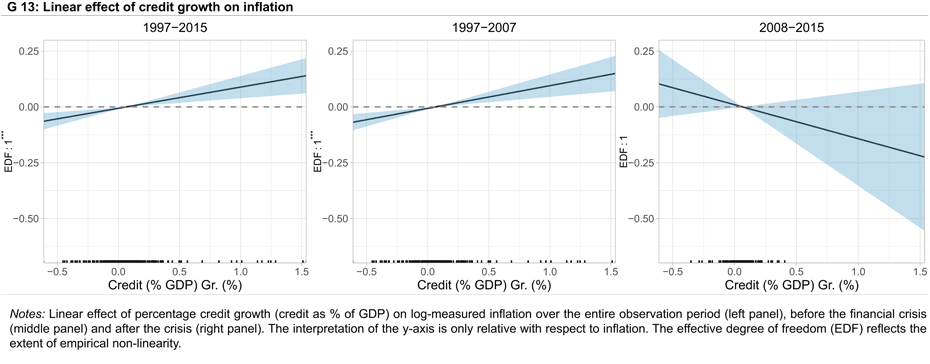

(iii) Money and credit growth

Overall, money supply growth (M2) is less relevant than credit growth. While credit creation has shown a linear relationship with inflation over the entire period (Chart G 13, left-hand panel), this pattern appears to have weakened or even turned negative after the global financial crisis (third panel). By contrast, the positive link between M2 growth and inflation has remained virtually constant.

(iv) Monetary policy and policy framework

According to Milton Friedman (1974, p. 1), "There is no technical problem about how to end inflation. The real obstacles are political." For this reason, in addition to demographic and macroeconomic factors, the study also examines the political structure, monetary policy strategies, and the independence and transparency of central banks. However, their explanatory power is low. Of the various political variables, only civil liberties were relevant, and their expansion after the crisis had a deflationary effect.

(v) Public finances

The impact of budget deficits and government debt on inflation has always enjoyed special attention among experts and politicians. There are two views on this. Milton Friedman (1970, p. 11) considered fiscal policy unimportant on its own. Thomas Sargent (2013, p. 213), on the other hand, asserted: "Persistent high inflation is always and everywhere a fiscal phenomenon."

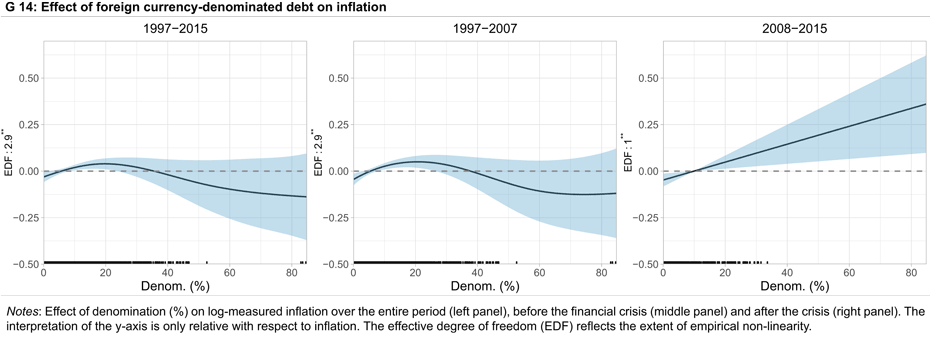

Unlike a large body of research, the results of the study indicate that government debt was not a major source of inflation in the period under review. What is important is how it was managed, in particular the share of foreign-currency-denominated external debt (see Chart G 14).

(vi) Past inflation

The study shows that current inflation is positively and linearly affected by past inflation, suggesting agents with adaptive expectations who use past inflation to predict future inflation.

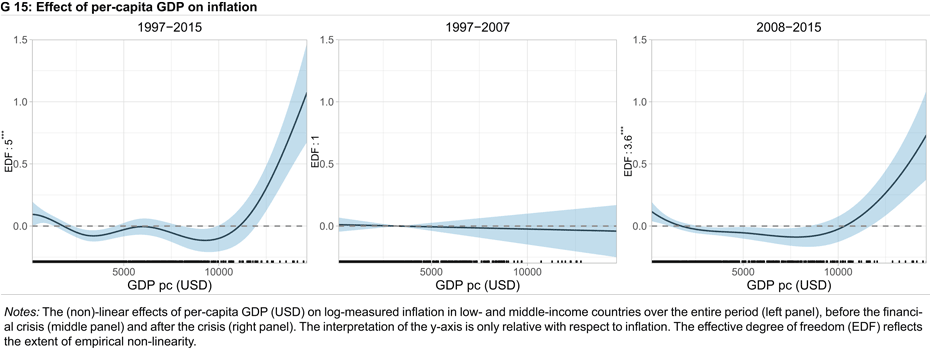

(vii) The real side

Across the entire sample, an increase in real per-capita GDP leads to higher inflation up to a level of USD 50,000, after which the effect flattens out. Low- and middle-income countries, however, present a very different picture. Before the financial crisis there was hardly any impact on inflation in these countries (see Chart G 15, middle panel). Since then we can see a weak negative association for incomes below USD 10,000 and an increase in inflation above this income threshold (third panel). Real GDP growth fuelled inflation but was less important than real per-capita GDP. The output gap has a non-linear relationship with inflation but plays a minor role compared with real per-capita GDP, although it empirically performs better than real GDP growth.

Conclusions

In summary, we have obtained four results that could have economic policy implications. The first result concerns monetary policy. The most important for the inflation process is the interaction of energy prices with energy rents. The effect of M2 growth has been weak and less relevant than credit growth. The effect of the latter on inflation even seems to have become negative since the global financial crisis. This suggests that monetary policy measures designed to stimulate credit creation with the ultimate aim of raising inflation may fail. Official inflation targeting has little explanatory power. Exchange-rate arrangements are more important. The evidence that central bank independence has only a small effect on inflation is consistent with the results of Baumann et al. (2021b). Second, the impact of civil liberties is the most compelling among a range of policy factors. Third, there is only a weak relationship between government debt and inflation. Finally, we have identified two structural forces – the ageing of the population and the formation of ICT capital – that impact the results in opposite directions. From a methodological perspective we show that a data-driven machine-learning approach is superior to economically based panel regressions for our dataset in terms of explaining inflation.

--------------------------------------------

1) Energy rent is calculated as the difference between the price of a commodity (coal, crude oil or gas) and the associated average production costs.

References

Baumann, F M, E Rossi, A Volkmann (2021a), "What Drives Inflation and How? Evidence from Additive Mixed Models Selected by cAIC", Swiss National Bank Working Paper 2021-12.

Baumann, F M, M Schomaker, E Rossi (2021b), "external pageEstimating the Effect of Central Bank Independence on Inflation Using Longitudinal Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimationcall_made”, Journal of Causal Inference 9(2), 1-38 and “Central Bank Independence and Inflation: Weak Causality at Best," VoxEU 02 July 2021.

Friedman, M (1970), "The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory", London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Friedman, M (1974), "Monetary Correction: A Proposal for Escalator Clauses to Reduce the Costs of Ending Inflation", IEA Occasional Paper, no. 41.

Sargent, Thomas J. (2013), "Letter to Another Brazilian Finance Minister." Republished in Rational Expectations and Inflation, 3rd edition: Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Contact

KOF FB Data Science und Makroök.

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland