Is inflation out of control?

- Business Cycle

- Monetary Policy

- Inflation

- KOF Bulletin

Inflation rates have risen significantly over the past year. In the United States in particular, inflation is increasingly becoming a problem to which the Federal Reserve (Fed) must respond. Inflation has also risen sharply in the euro area. In Switzerland, the situation is still somewhat less serious.

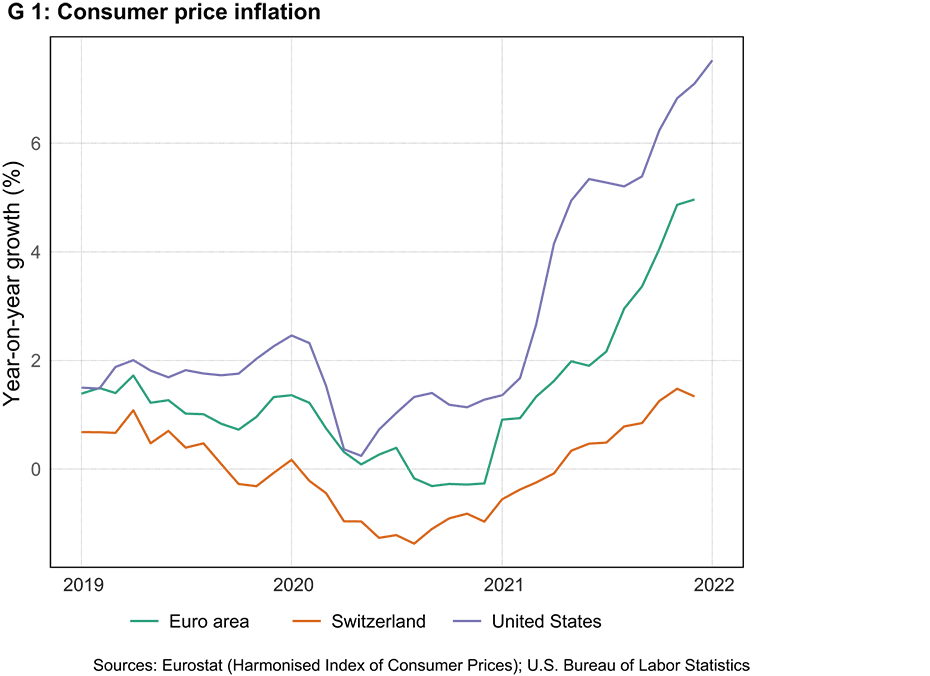

Inflation, as measured by the growth rate in consumer prices, has risen significantly in many countries after the lifting of various restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic (see chart G 1). In the US, this rate now clearly exceeds the Fed’s inflation target, which is slightly above 2 per cent.1 The euro area, too, has an inflation rate of around 5 per cent, which is higher than the 2 per cent target set by the European Central Bank (ECB). Only in Switzerland is inflation still comfortably within the target range (0-2 per cent) set by the central bank (Swiss National Bank [SNB]).

This article explores these differences using the so-called Phillips curve. In its modern version, this states that inflation fluctuations are related to three factors: disruptions or improvements in the production process for goods and services, business cycle fluctuations, and changes in inflation expectations. These three factors not only have varying effects on inflation.2 Monetary policy should also respond differently depending on the cause of the change in inflation. This article uses this theoretical model to examine the various inflation trends and explains what this means for monetary policy.

Disruptions in the production process for durable goods

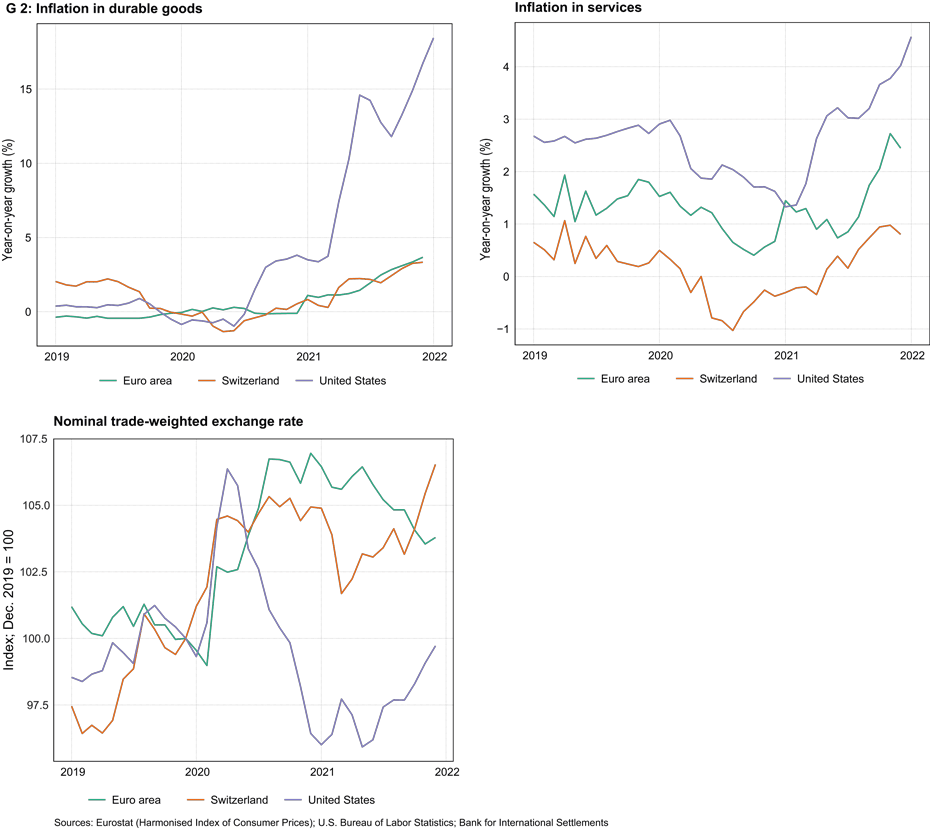

It is well known that disruptions in value chains and supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic have led to shortages of imported consumer durables, causing both supply problems and price increases. In fact, inflation in durable goods is significantly higher than that in services in all three currency areas (see chart G 2). However, inflation in durable goods has risen most sharply in the US. This could be due to the fact that the US imports a larger share of its goods from China than Switzerland does.

However, exchange-rate fluctuations are also likely to play a role. Most consumer durables are imported, which makes their prices dependent on exchange rates. Indeed, the Swiss franc has appreciated by more than 6 per cent since the beginning of the pandemic (see chart G 2; an increase in the index means a currency appreciation). The rise in the euro was somewhat less pronounced. The US dollar is trading at about the same level as it was before the pandemic. However, the exchange rate cannot explain the entire difference in inflation rates. According to Stulz (2007), an unexpected 1 per cent appreciation in the currency leads to a reduction of about 0.2 per cent in consumer prices in Switzerland after twelve months. According to this rule of thumb, inflation in Switzerland would be about 1 percentage point higher without any currency appreciation.3 This is significantly higher, but still not as high as in the US. 4

Performance of the economy

Another reason why inflation can rise is improvements in the economy. If the economy is doing well, i.e. demand exceeds the supply of goods and services, companies demand higher prices. In addition, employees demand higher wages as firms compete for skilled workers in a tight labour market. Higher wages cause firms to incur higher costs, which they in turn pass on to consumers in order to protect their margins (see, e.g., Renkin et al., 2020). This is especially reflected in higher prices for services that are particularly labour-intensive.

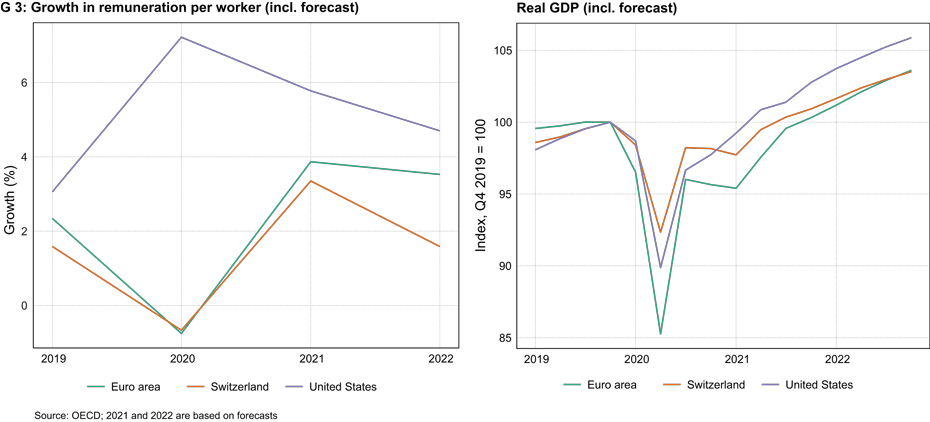

In fact, chart G 2 shows that inflation in services has increased in all three currency areas. In Switzerland and the euro area, however, services inflation is significantly lower than it is in the US. In addition, chart G 3 shows that wage growth in Switzerland is, on average, lower than it is abroad.5 Are these differences due to variations in economic activity? Chart G 3 shows that real GDP in the US actually returned to pre-pandemic levels sooner than it did in Switzerland and the euro area. This stronger economic performance is thus probably another reason why inflation is higher in the US. According to this yardstick, however, the economy is doing better in Switzerland than it is in the euro area. Economic trends therefore cannot explain the differences in inflation between Switzerland and the euro area. In fact, nominal wage growth is higher in the euro area than it is in Switzerland despite the former’s weaker economic growth.

Inflation targets, inflation expectations and wage-price spirals

The final reason why inflation evolves differently in the three currency areas is that central banks have different inflation targets and economic agents have different inflation expectations. The two variables are interdependent since, if the central bank does a good job, long-term expected inflation should not deviate too far from the inflation target. In the theoretical model, moreover, today’s inflation depends on future expected inflation, since wages are rarely adjusted. If workers and trade unions expect prices to rise sharply next year, they will demand higher wages today to keep their purchasing power constant over the course of the year. Companies pass on these higher wage costs to consumers in the form of price increases for their products, which leads to inflation. In extreme cases, this can trigger a wage-price spiral, which causes higher inflation regardless of the economic cycle.

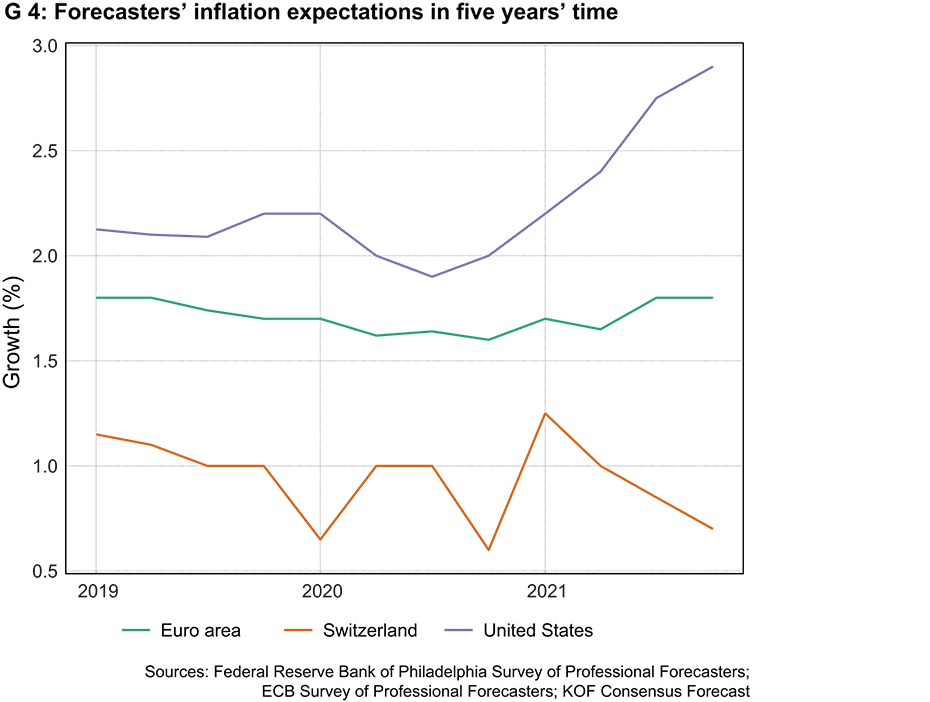

That’s the theory then. Are there any signs of a wage-price spiral in practice? According to chart G 3, wages are rising particularly sharply in the United States. Chart G 4 shows that long-term inflation expectations in the US have grown. They are also somewhat higher than the Fed’s inflation target. Inflation expectations have risen in the euro area as well but are still below the ECB’s inflation target. In Switzerland there is no observable increase. Moreover, expectations are comfortably within the SNB’s target range. It therefore stands to reason that the different levels of wage growth in the three currency areas – as well as the different levels of inflation in services – are also due to differences in inflation expectations.

Implications for monetary policy

The higher inflation in all three currency areas has been partly due to disruptions in value chains and supply chains. The subsequent rise in the prices of imported goods has been slightly offset by currency appreciation in the euro area and Switzerland. These differences can also be explained by better economic performance and an increase in inflation expectations in the US. What are the implications for monetary policy?

Insofar as the higher inflation is due to disrupted value chains and supply chains, monetary policy should not be tightened. The reason is simple. These price increases provide important relative price signals to economic agents: there is a disruption in the economic process for which a market solution is needed. Or to illustrate this with another example: if the government introduces a carbon tax, the central bank should not tighten monetary policy to stabilise energy prices, even if this causes inflation to deviate from target. The purpose of the carbon tax is to slow down climate change. The price increase sends an important signal to market participants to adjust their production accordingly.

How should monetary policy react to a cyclical rise in inflation? Normally, in such situations, the central bank resorts to interest-rate hikes.6 Such tightening of monetary policy does not cause major disruption since the economy is booming and the central bank is merely slowing down the economy. In fact, the Fed recently announced that it is adopting a tightening stance earlier than expected. Given the weaker inflation and economic activity levels in Switzerland and the euro area, the ECB and the SNB are likely to wait a little longer.

Finally, central banks must try to break any wage-price spiral in order to fulfil their legal mandate. In the past, many central banks have responded to such spirals by raising interest rates. Although this instrument works, there is a great danger that it will cause a painful slump in the economy. If a central bank quickly stifles inflation, but workers demand wage increases owing to their still high inflation expectations, it is likely that companies will lay off some of their workforce because of their high costs. Central banks should therefore not allow such spirals to develop in the first place. This is probably a major reason why the Fed has now started tightening. Whether this tightening has already come too late will be revealed over the next few quarters by the performance of inflation and the economy. For the ECB and the SNB, however, there are still very few signs of any change in long-term inflation expectations. Consequently, these two central banks still have a little more time before they need to adopt a tightening stance.

______________________________________________

1 The Fed defines its inflation target of 2 per cent using the consumption deflator. Measured in terms of the consumer price index, this results in an inflation target of slightly above 2 per cent, as consumer price inflation is usually slightly higher than consumer deflator inflation.

2 There has often been debate about whether the recent rise in inflation is permanent or temporary. More important for good monetary policy, however, is what is causing the rise in inflation. It is often assumed that disruptions in the production process are of a short-term nature, that economic developments influence inflation in the medium term and that expectations determine the long-term inflation trend. However, this is not necessarily true.

3 However, this study does not take into account more recent data, especially since the financial crisis. More recent studies suggest a somewhat weaker relationship (see, for example, Auer, Burstein and Lein, 2021). This rule of thumb is therefore likely to slightly overestimate the effect of exchange rates.

4 The impact of durable goods on overall inflation is relatively small. Their weight in Switzerland’s consumer price index is around 8 per cent. Services, on the other hand, account for almost 60 per cent.

5 However, comparisons made during the COVID-19 pandemic should be interpreted with caution. Remuneration per worker depends, by definition, on the number of workers. This figure has fluctuated considerably during the pandemic and has also depended on various support measures such as short-time working. Nonetheless, projections from 2021 onwards indicate that wage growth is highest in the US and lowest in Switzerland.

6 Nowadays, central banks also have to decide how to unwind bond-buying programmes.

References

Raphael Auer, Ariel Burstein and Sarah Lein, 2021, “Exchange Rates and Prices: Evidence from the 2015 Swiss Franc Appreciation”, American Economic Review, 111(2), pp. 652-86, external page https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181415

Tobias Renkin, Claire Montialoux and Michael Siegenthaler, 2020, “The Pass-Through of Minimum Wages into US Retail Prices: Evidence from Supermarket Scanner Data”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, external page https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00981

Jonas Stulz, 2007. “Exchange rate pass-through in Switzerland: Evidence from vector autoregressions,” Economic Studies 2007-04, Swiss National Bank, external page https://www.snb.ch/n/mmr/reference/economic_studies_2007_04/source/economic_studies_2007_04.n.pdf

Contact

Schweiz